Sections: Before the Anglian glaciation. Known sources in Pembrokeshire of Anglian igneous erratics. Spot the difference. Reworked Anglian igneous erratics of Gower beaches. Cockles track the Anglian ice. Cave system formed under the Anglian ice. Anglian landforms on Gower. A prominent sub-glacial channel. Ice-sculpted cliffs. Enigmatic boulders at Pwll-du. Fluvioglacial gravel boulders. Fossiliferous boulders. Missing limestone – a lot of it. Understanding Gower’s missing limestone by looking at a Swansea Valley cave system. Geology and ice flow.

I’m working on a new project on Gower. Several novel observations and surprising inferences bear on what we call the Anglian glaciation, which affected our Gower peninsula some 450,000 years ago. Evidence for this far-reaching but rather poorly known glacial episode was widely obscured by the more recent Welsh Ice of the Last Glacial Maximum, which got here about 23,000 years ago. We have long known that the older, major glaciation reached far into the Bristol Channel, across Gower and much of old Glamorganshire, reaching what is now Devon and Somerset. Many people will be aware of a long-running, media-fuelled ‘debate’ regarding the delivery to Stonehenge of a suite of rocks – the so-called bluestones – most of which certainly originated in Pembrokeshire. I shall not engage with the negative elements of that ‘debate’, which rather uncompromisingly set human transport against glacial (erratic) explanations. I do, however, briefly explain what seems reasonable to believe and might just nudge the reader towards a possible half-way house, in the following section entitled ‘Stonehenge’. The Anglian ice certainly crossed Gower in the direction “Towards Stonehenge” and I shall run with that hook for now, probably provoking a similar singular response to that afforded for my earlier book title “All our own water…” The part-cryptic titles perhaps reflect my warped, provocative sense of humour… I prefer civilising humour to invective.

I shall illustrate the hard evidence that is in the extraordinary array of igneous-rock erratics delivered to Gower by the Anglian ice, and I will suggest that some sculpted landforms of valleys and cliffs on Gower possibly record erosion by the passage of that thick ice sheet. Perhaps we have overlooked a major landscape former… I shall revisit the evidence found at our cave dig at Cockle Pot, near Llethrid, where Carmarthen Bay marine sediment was smeared eastwards by Anglian ice onto the peninsula, and then illustrate and attempt to explain some exciting new caving-team discoveries that seemingly are unique in finding locally a cave that formed mainly under the ice. This will be a section in effect ‘coauthored’ with my caving friends, who have supplied the findings. A further seemingly ridiculous occurrence of an exhumed cave fill involving Anglian fluvioglacial outwash will test my credibility in the eyes of the reader, while nearby fossiliferous boulders seemingly reflect a change of the climate! Also, we will consider some measure of the dramatic rate at which our coastline is eroded. By looking inland at a cave system (Ogof Ffynnon Ddu) in the Swansea Valley, we may begin to grasp how much limestone-with-caves is missing here from above our heads, and how much we have lost to sea level rise. What we have on Gower in terms of accessible limestone-bearing cave systems is a fraction – a horizontal slice – of what there once was… So, here goes. (Reader please be aware that this is work in progress – substantially incomplete and liable to change! I am open to constructive criticism and discussion of my ideas – see the section ‘Feedback’ – and would hope to be properly acknowledged if they are recycled.)

Before the Anglian glaciation

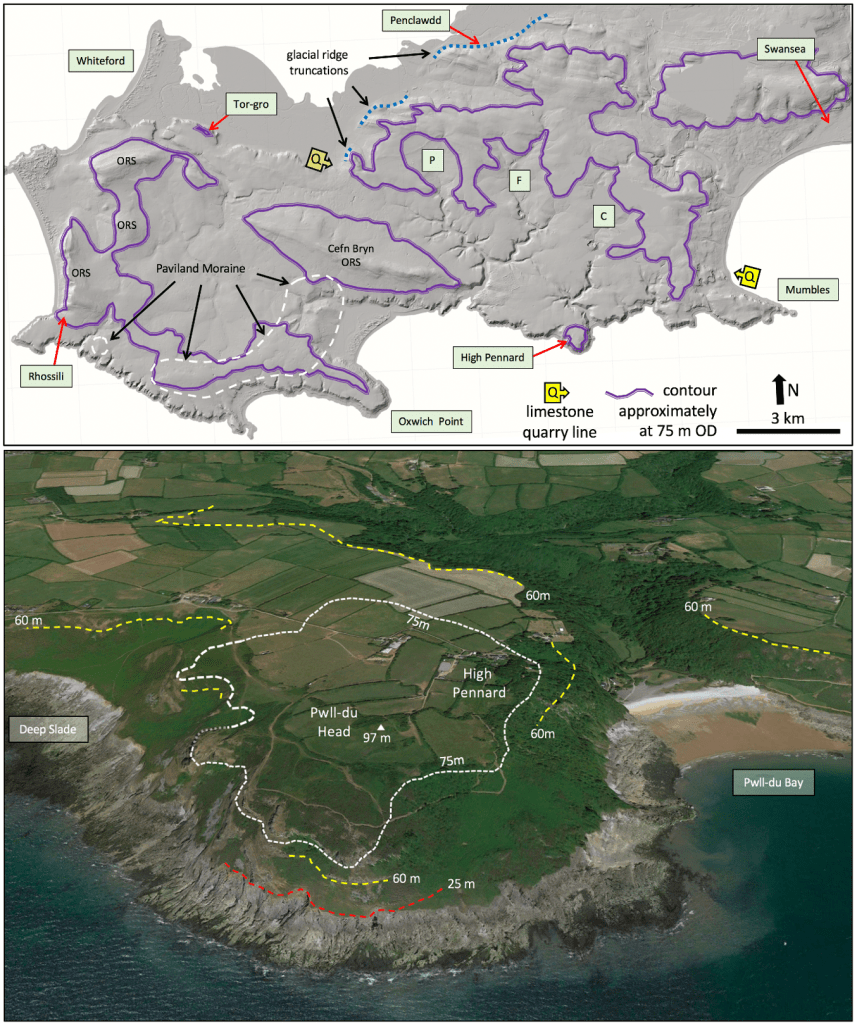

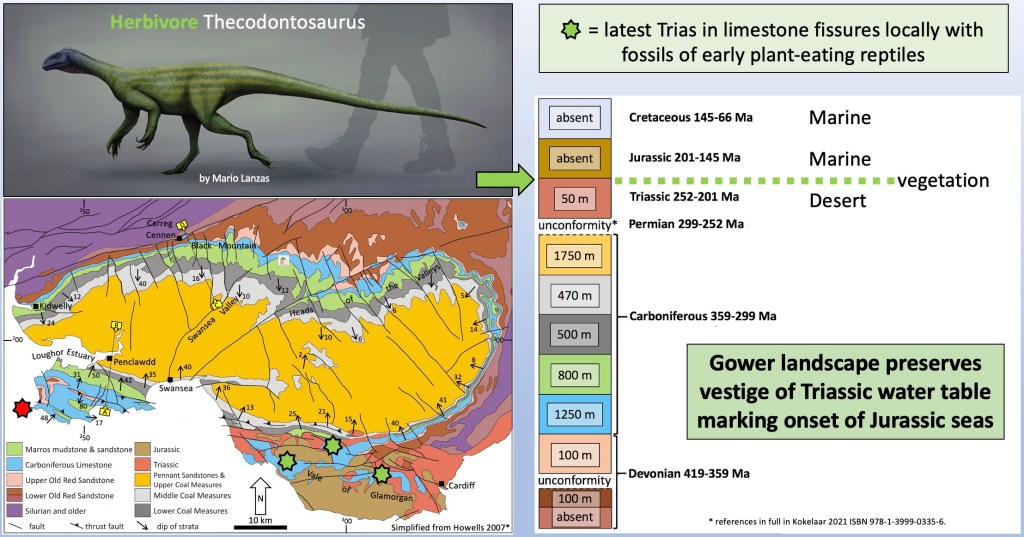

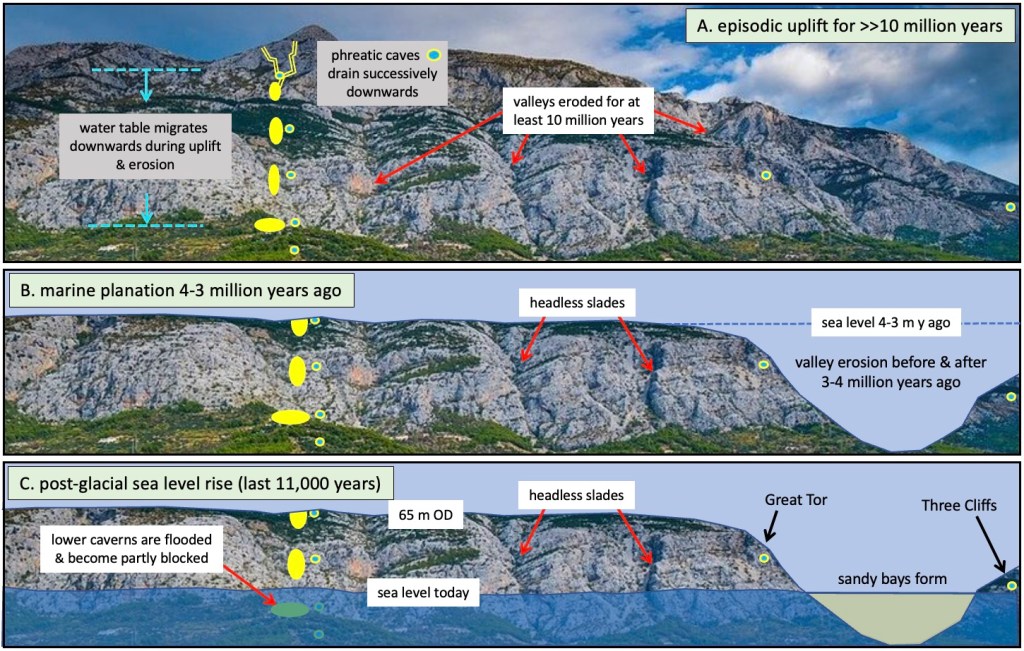

We know that just before the Quaternary Period – the Ice Age that started some 2.58 million years ago – Gower limestones in particular were widely planed to a gently sloping surface by an advance of the sea (e.g., Fig. 1). I discuss this marine planation in the book (Kokelaar 2021). It appears that the sea advanced and eroded the surface of Gower up to what is now about 75 m OD. At the maximum marine advance there would have been an archipelago of islands, especially of the more resistant Old Red Sandstone, e.g., now forming Rhossili Down and Cefn Bryn, and the tough Pennant Sandstone ridges of north Gower (Fig. 2).

We know very little of what happened during the Quaternary Ice Age before the Anglian glaciation. There were several alternations of extreme cold – the glacial episodes – and interglacial warmer conditions. We know that sea level fluctuations, due to the varying amount of on-land ice globally (i.e., not contributing to sea water), resulted in successive cuts that formed our cliffs, both above and below present-day sea level, and we can only roughly guess at what the land surface was like.

Figure 1. South Gower scenery is dominated by a gently sloping marine platform that was cut just prior to the Quaternary Ice Age. The cliffs, including versions currently offshore, were mostly cut into this platform during successive relative high stands of the sea during the Quaternary Period. The sea cliffs are riddled with caves and solution tubes and the surface has numerous depressions that are sink holes and/or collapse pits that widely connect in three dimensions within the limestones. The Anglian ice sheet must have advanced here over cavernous karst-featured land that was at least in part modified by periglacial weathering and sedimentation. It is inferred below that this ice shaped some of our valleys and cliffs during its passage.

Figure 2. (Fig. 23 of Kokelaar 2021). (Top) Shaded-relief LiDAR image of peninsular Gower highlighting aspects of the topography. The purple contours at approximately 75 m OD outline the higher parts of the surface that perhaps were beyond the reach of the sea (beyond marine planation). One might imagine this as a short-lived archipelago of islands lacking cliffed shorelines. Cefn Bryn and the western summits of Old Red Sandstone (ORS) probably were prominent landscape features for considerable geological time. The ‘limestone quarry line’, Q-Q, indicates the string of numerous old and more recent quarries in the upper parts of the Carboniferous Limestone succession. The Late Pliocene marine planation surface is only well developed south and west of this quarry line, on the limestone. Limestone outcrops seemingly not reached by the sea include High Pennard, the ridge of Oxwich Point, Tor-gro and an area west of Mumbles. The Paviland Moraine (from Shakesby et al. 2018) formed some 23,000 years ago from the Devensian glaciation. (Base data © Natural Resources Wales). (Bottom) Oblique Google Earth view north over High Pennard and the seaward end of Bishopston Valley. Like the purple contour in the image above, the 75 m OD white contour distinguishes high ground that may have remained beyond the reach of waves during the Late Pliocene. The more widely developed marine planation level here is at about 60 m OD. Both Anglian and Devensian glacial ice flowed across here. The enigmatic boulders discussed below occur on the west side (left) of Pwll-du Bay. Karst landscape and periglacial features following recession of the Anglian ice are implicated in explanations of the enigmatic boulders, below.

Known sources in Pembrokeshire of Anglian igneous erratics

Figure 3. Foreground perched boulder of gabbro on St David’s Head (SM722 279), which, with nearby Carn Llidi and the northern Bishops and Clerks skerries (part seen far right), supplied distinctive gabbros. The highest part of Ramsey Island (centre) yielded the highly-distinctive silicic volcanic rock known as the Cader Rhwydog Tuff, while other prominences and skerries are related silicic lavas and intrusions that sourced distinctive crystal-rich erratics.

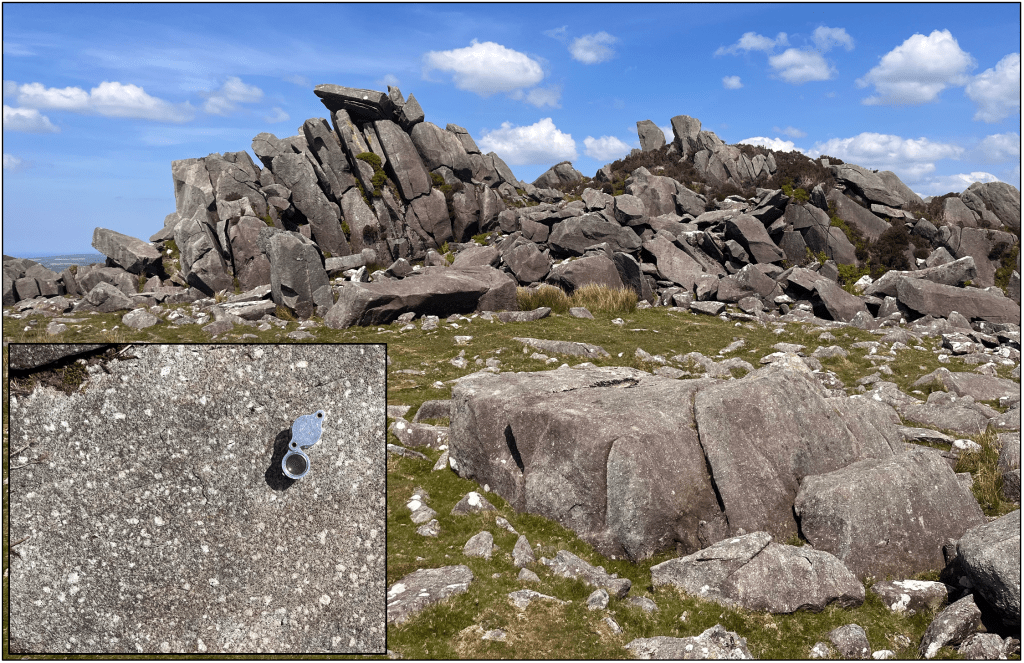

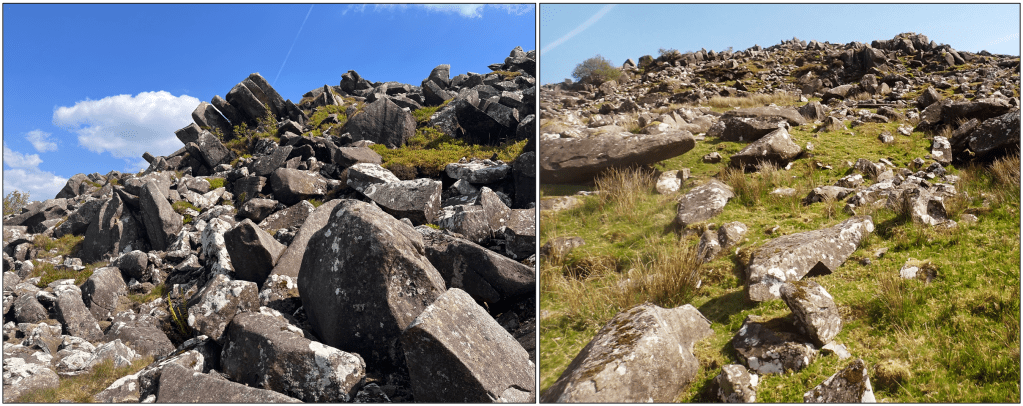

Figure 4. A typical craggy summit outcrop of spotted dolerite at Carn Menyn, eastern Preseli (SN141 325). The rock naturally breaks into slabby monoliths with flat surfaces along original joints and rounded shoulders and sides where ‘weathered’ over millennia, conceivably for more than 450,000 years. The white spots are original plagioclase crystals or crystal clusters that became hydrothermally altered to clumps of fine-grained secondary minerals, which, in turn, were recrystallised during regional burial and heating. (See explanatory note.) This rock type occurs locally as erratics and is the most common of the Stonehenge ‘bluestones’. It has not been found as erratics on Gower or farther east in old Glamorganshire.

Figure 5. Outcrop of spotted dolerite at Carn Goedog (SN128 332). The slope abounds with naturally formed and fallen slabby and polyhedral (multi-faceted) columnar, weathered monoliths. Dolerite intrusions like these in the Preseli hills are common widely in western and northern Britain and everywhere their upland outcrops break, weather and collapse in similar fashion, without any human intervention.

The altitudes of the spotted dolerite outcrops, which form most of the highest and main peaks in the eastern Preseli hills, are Carn Menyn – Carn Gyfrwy 365-350 m OD (Fig. 4), Carn Breseb 320 m, Carn Goedog 300 m (Fig. 5), and Cerrigmarchogion 360-410 m. The outcrops occur in an area of roughly 4 km2 and probably represent a single intrusion, although the ground between them is partially covered by superficial debris. Thorough mineralogical and geochemical analyses by Richard Bevins and colleagues effectively ‘fingerprint’ these outcrops as the unique source of the spotted dolerite bluestones at Stonehenge, which has led those favouring human transport to seek and infer one or more quarries here from which the stone was deliberately carried away.

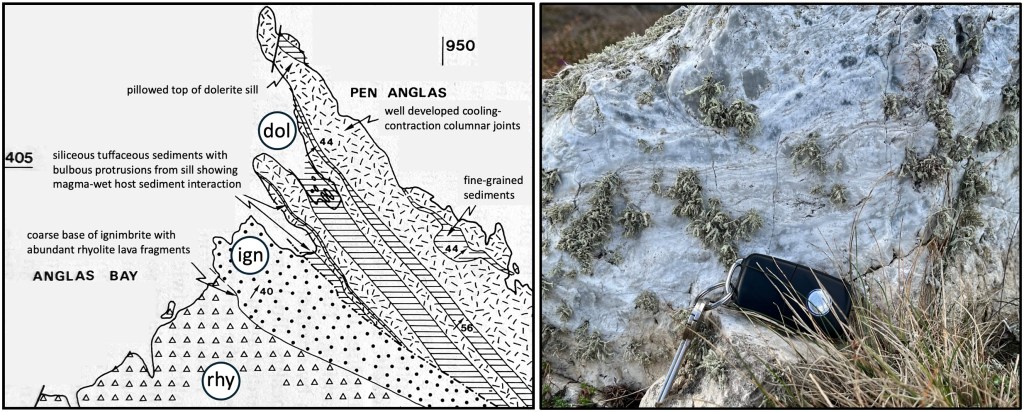

Figure 6. West of Fishguard, the prominent headlands Penfathach, Y Penrhyn and Pen Anglas (shown here) expose large craggy, sea-cliff outcrops of diverse rhyolites, silicic ignimbrites and non-spotted dolerite that must have contributed to the erratic load of the overpassing Irish Sea Ice Sheet and can be visually matched with samples from Gower. The most prominent headland, with the fog-horn housing and pillar-monument, comprises columnar-jointed dolerite sheets (dol) intruded into volcanic sediments, while the middle of the section is silicic ignimbrite (ign) and the main exposure to the right is variously banded, nodular and brecciated rhyolite (photo on right). This coast faces north and the smoothly rounded headland surface profile here almost certainly registers erosion by the Anglian Irish Sea Ice Sheet that was forced up and over here. Exposure-age dating (McCarroll et al. 2010, p. 1849) registers little or no reworking by Devensian ice around here. (Map from Kokelaar et al. 1984, p. 308).

Spot the difference

What is ‘spotted dolerite’? Igneous rocks form from molten material – known as magma – which can either be erupted via volcanoes at the Earth’s surface, where it tends to cool quickly, or be intruded at depth to cool more slowly. Magmas may initially partly crystallise so they contain individual free crystals (phenocrysts) or clusters of them (glomerocrysts). Preseli dolerites represent magmas intruded as sheets beneath erupted lavas of similar composition (Fishguard Volcanic Group) and within what had been sea-floor sediments, at the time probably retaining some water. Some of the magmas contained cm-scale free crystals of plagioclase, others did not. In the case of the developments of ‘spots’, it appears that late-stage volatiles and heat from the magma caused hot-water circulation (i.e., hydrothermal) that affected the cooling and crystallisation of the intrusion. Here fresh large crystals of plagioclase in the cooled magma became replaced by fine-grained secondary minerals. Later, during deeper burial with regional heating and increased pressure, owing to ‘mountain building’, the minerals recrystallised finally to form the spots we see today (Bevins et al. 2021). The Preseli spotted dolerite outcrops only occur in one small area of the eastern Preseli hills, forming the highest summits and conceivably belonging to a single intrusion now partially masked by superficial deposits.

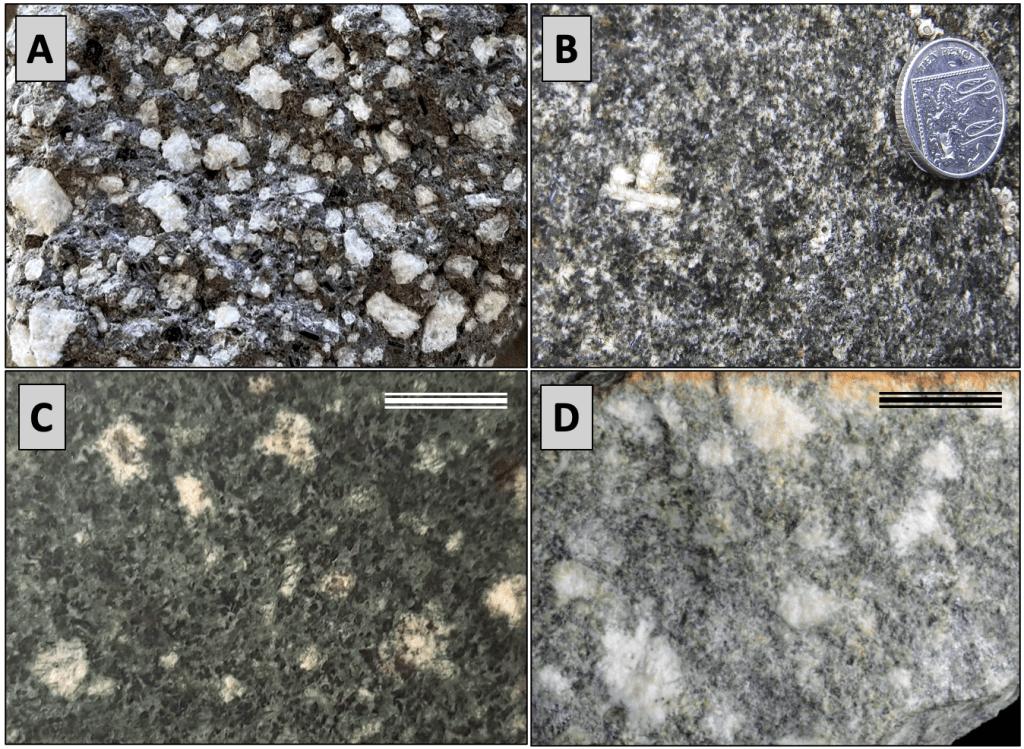

Figure 7. A. Perfectly fresh plagioclase crystals (phenocrysts) with sharply defined edges in a fine-grained lava matrix (collected from a Chilean volcano). B. Rather dirty-looking recrystallised plagioclase crystal cluster in the Limeslade dolerite erratic on Gower (Fig. 11), considered to be typical of crystal-bearing but non-spotted dolerites derived from Pembrokeshire. C and D. Examples of Preseli spotted dolerites showing the fuzzy outlines characteristic of an early phase of hydrothermal alteration. Scale bars are 1 cm. (Photos C and D courtesy of Richard Bevins).

Reworked Anglian igneous erratics of Gower beaches

The following pictures (Figs 8-11) show the truly remarkable diversity of igneous-rock erratics found on Gower, currently more than 20 distinct types. None of this represents new research findings, but it is a unique pictorial compilation; many erratic types have long been known to record erosion of distinctive rock outcrops that occur in Pembrokeshire. Although it is impossible to locate sources precisely, several rock types unmistakably come from known relics of ancient volcanoes and their sub-volcanic plumbing systems*, i.e., their associated magmatic intrusions, in Pembrokeshire. Thus R below is from a unique volcanic unit on Ramsey Island and certain gabbros with distinct mineralogy and texture derive from the major headland and skerry-forming intrusions centred around St David’s Head. Along with the volcanics that form Skomer Island and sea cliffs west of Fishguard (e.g., Fig. 6), the igneous rocks evidently formed tough and upstanding obstacles within the flowing ice, then perhaps beneath the ice and/or as nunataks (partly exposed) and now widely remaining as sculpted prominences arising from the marine-eroded coastal platform. *(The author has mapped in detail Ramsey Island, the St David’s Head intrusions, and the coastal section west of Fishguard, and is familiar with the Skomer volcanics).

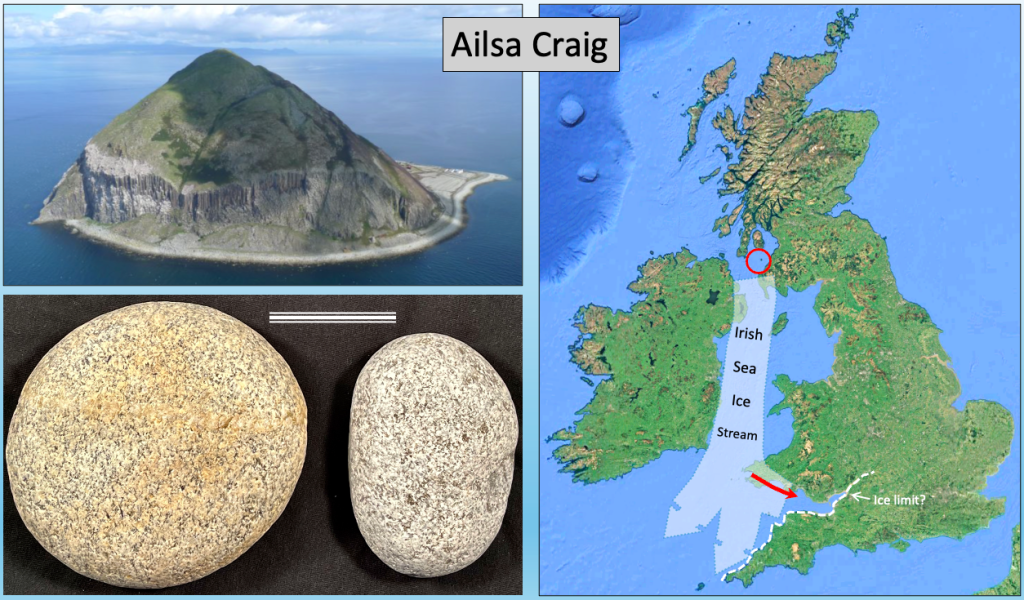

That said, there is a bewildering array of erratic exotica of unknown origin, with just one exception being cobbles of a fine-grained granite known to come from Scotland, specifically the steeply cliffed island of Ailsa Craig in the Firth of Clyde. This erratic type, named ‘riebeckite microgranite’ (Fig. 10), was recognised on Gower by TN George (1933), with Ailsa Craig already known then to be the sole source of such rock, quarried, cut and polished to make curling stones. South Gower remains its southernmost known natural occurrence.

The Ailsa Craig erratics are particularly important because they confirm that the transporting ice came via western Scotland, before moving south through the Irish Sea and deflecting eastwards into what is now the Bristol Channel. This major flow of ice is known as the Irish Sea Ice Stream (Fig. 12). The Ailsa Craig erratics also allow that several other Gower erratics probably also come from Scotland and/or Northern Ireland, where various other similar-looking igneous and foliated rocks abound. Again, this is not new. Jehu (1904) recorded diverse erratics found in northern Pembrokeshire and, better informed than myself, he recognised more specifically their sources in southwest Scotland, Northern Ireland and western Scotland. Recently, the author found at Horton on Gower (SS475 855) two erratics rocks, one characteristic of the Grampian Highlands, and the other probably from the Hebrides, both north of Also Craig. (See account concerning the Altar Stone in the section on Stonehenge).

(Note: Exotic rocks that arrived on Gower beaches as jettisoned ballast are generally easy to distinguish from reworked glacial erratics, as they occur in clusters close to the low-tide limit where they were dumped from boats, near to known limestone quarry sites. Most of the erratics illustrated below occurred as very sparse constituents of storm embankments at or above the normal limit of high tides. They represent the erosional reworking of Anglian glacial deposits that remained on Gower after the major ice sheet melted away some 450,000 years ago.)

(Scale bar is always 5 cm)

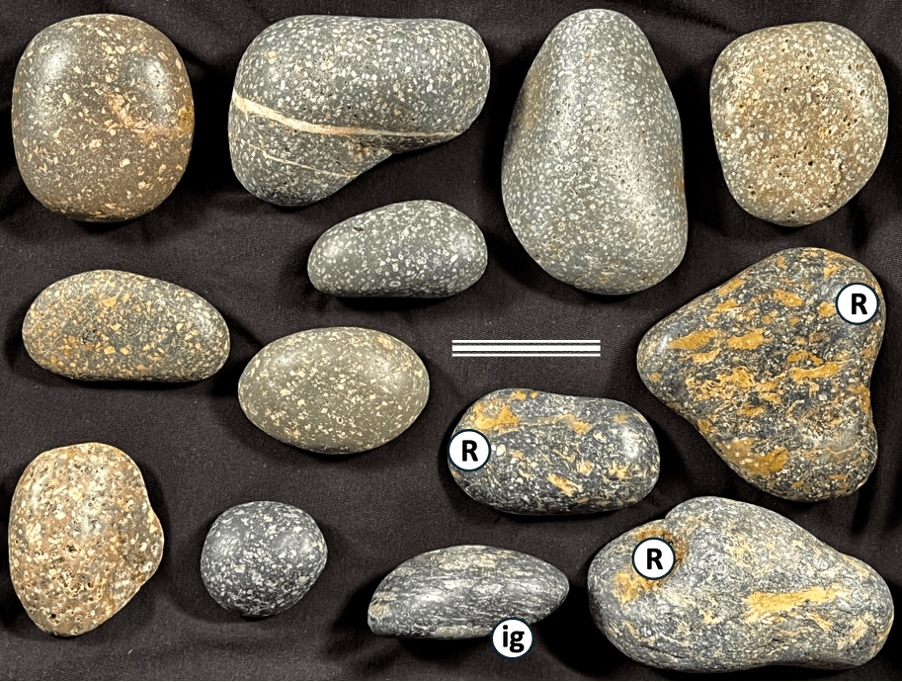

Figure 8. Silicic volcanic and shallow-intrusive rocks: (All collected from Ram Grove SS429 865). R is the distinctive ignimbrite (Cader Rhwydog Tuff) exposed on Ramsey Island; ig is welded ignimbrite, probably also from the Ramsey volcanic centre. The reminder is plagioclase-phyric (mostly) silicic lavas or shallow-emplaced intrusions like those of Ramsey Island rhyolites and microtonalite.

Figure 9. Mafic intrusive and extrusive rocks: (Top two rows collected from Horton SS475 855). Top row gabbro and coarse dolerites are probably from St David’s Head / Carn Llidi / Bishops and Clerks intrusions. Middle row and bottom left (latter collected from Ram Grove SS429 865) are successively finer dolerites akin to sills of coastal north Pembrokeshire but are of uncertain specific origin. Bottom middle and right are amygdaloidal* basalt, possibly from Skomer (collected from north Rhossili SS405 923; accompanied there by plagioclase-phyric silicic volcanics). * (Amygdales are mineral-filled original gas bubbles in lava).

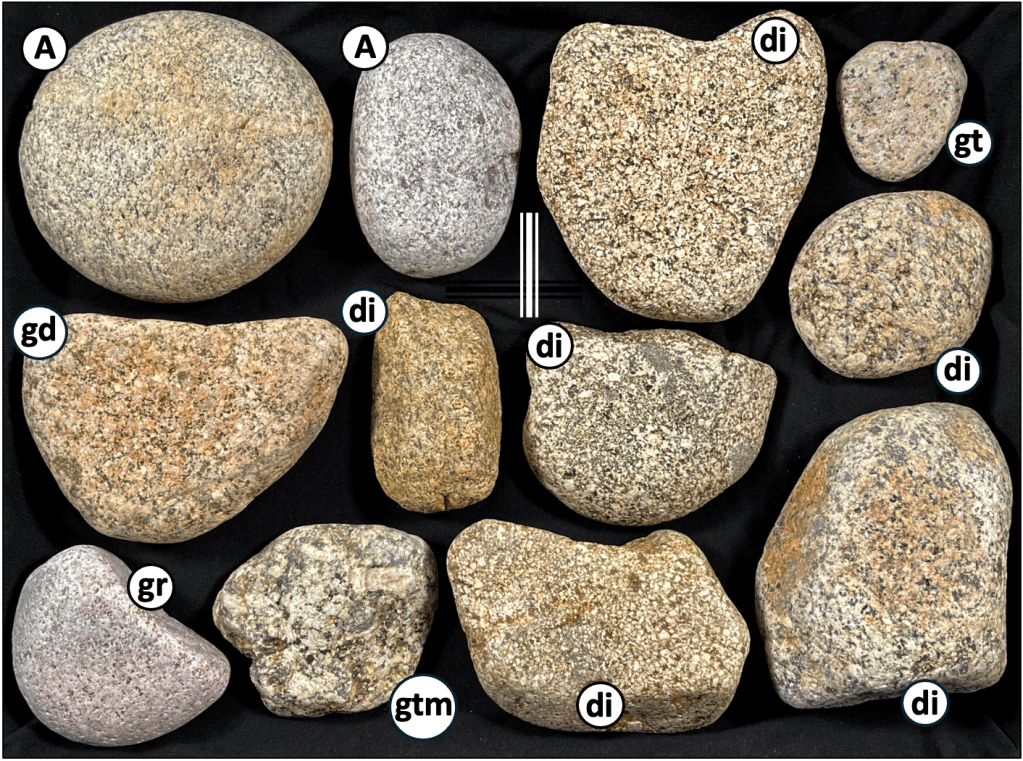

Figure 10. Silicic and intermediate intrusive rocks: A is riebeckite microgranite transported to Gower from Ailsa Craig in the Firth of Clyde, western Scotland, di are diorite-quartz diorite (with dark patches that are mafic inclusions), gd is granodiorite, gt is granite, gtm is a 2-mica granite, gr is granophyre (samples collected from Ram Grove SS429 865, south Oxwich Point SS500 850 and Horton SS475 855). All except A are of unknown origin.

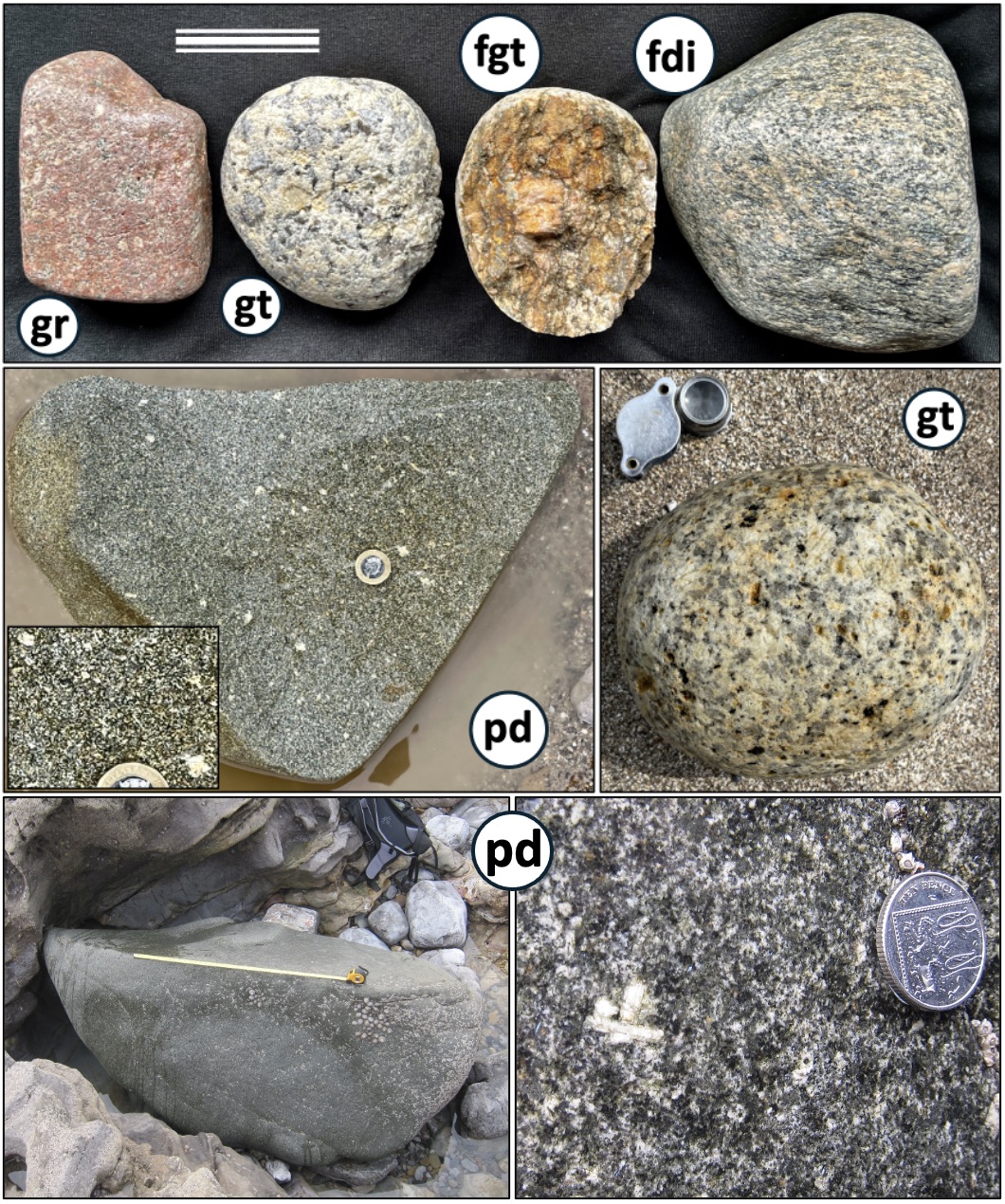

Figure 11. Diversity of igneous erratics: (Top row collected from Horton SS475 855). gr is granophyre, gt is granite, fgt is foliated granite and fdi is foliated diorite; both foliated varieties are possibly from Scotland. Middle row gt is from Bantam Bay SS5743 8668 (Pwll-du) and pd is porphyritic (non-spotted) dolerite from Horton SS475 855. Bottom is the porphyritic dolerite boulder on the intertidal platform at Limeslade (SS624 870), weighing roughly 4 tonnes. Tape measure shows 1 m. Probable Skomer silicic volcanic conglomerate occurs as similarly large boulders below Western Slade (SS484 855; Kokelaar 2021, Fig. 57).

Figure 12. Top. Map of the Bristol Channel area showing in yellow the most probable Anglian ice-transport path based on unequivocal occurrences on Gower and farther east of igneous erratics transported east-southeastwards from Pembrokeshire by the Irish Sea Ice Stream. ‘Spotted dolerite’ characteristic of Preseli summit outcrops is not found as erratics within the main trail (shaded yellow) whereas it does form many of the Stonehenge bluestones. This relationship, between glacial-ice movements manifestly “towards Stonehenge” and the lack of a clear glacial trace right up to Stonehenge (the contentious reach) is the root of the controversy around glacial versus human transport of the bluestones. The ‘Likely Local Welsh Ice’ (pale blue arrows) would probably have been of variable reach during the two main glaciations (Anglian and Devensian) and it is conceivable that the ‘Limit of Preseli spotted dolerite erratics’ (shown in green) reflects local ice of the later glaciation that partly buried Anglian deposits, as occurred on Gower (Kokelaar 2021, figure 46 and below). Bottom. The Ailsa Craig erratics on Gower prove transport from western Scotland via the Irish Sea Ice Stream. Other exotic erratics on Gower probably also came the same way, including metamorphic rocks from the Grampian Highlands and from the Hebrides… (See discussion of the Altar Stone origin, below).

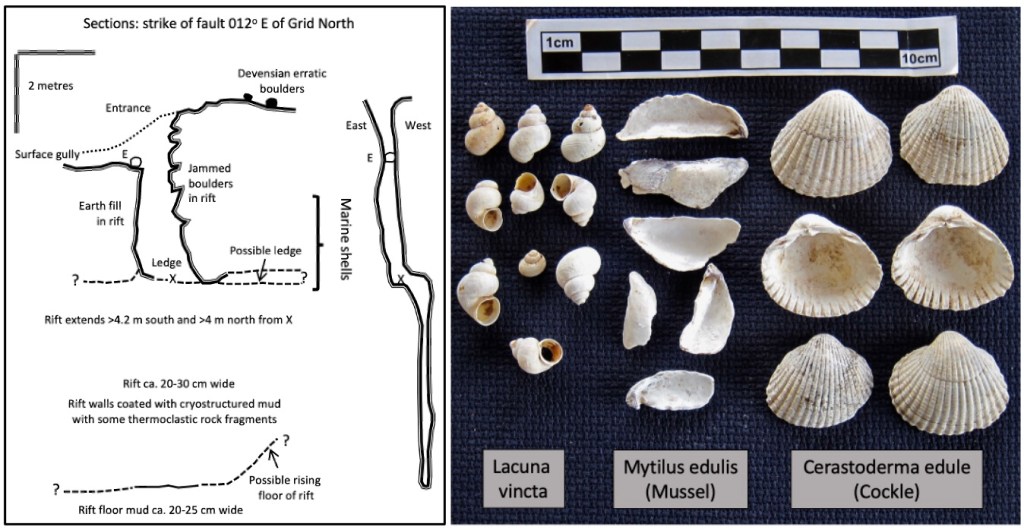

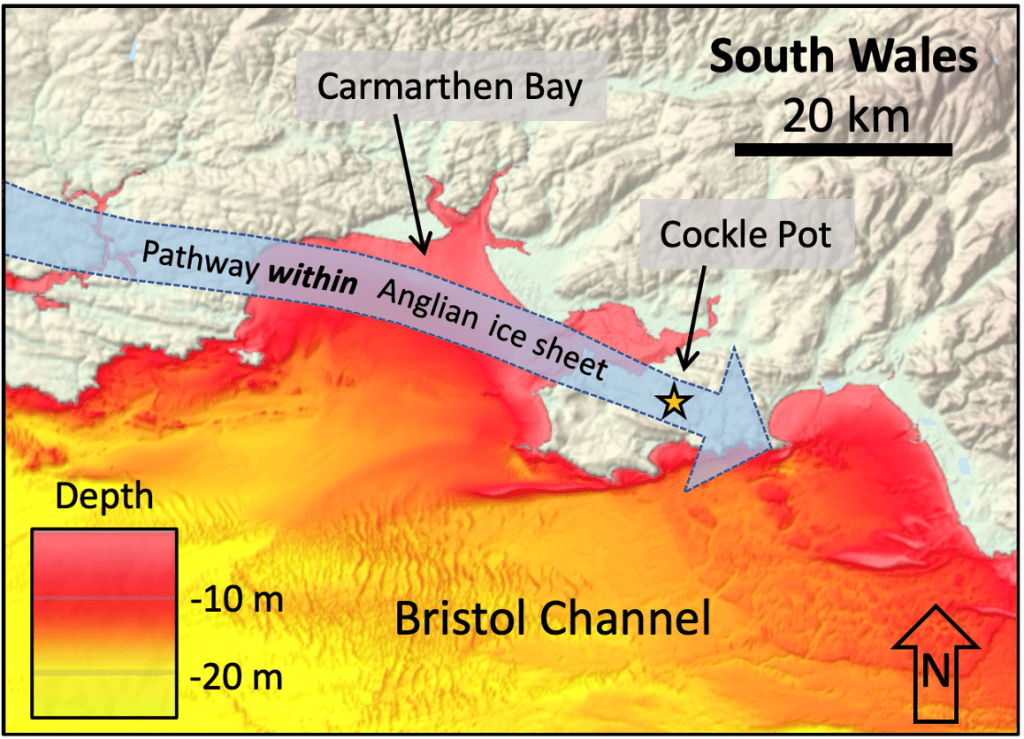

Cockles track the Anglian ice

This cockles evidence is culled from my book (Kokelaar 2021, pp. 160-161). In one of our attempts to recover access into Llethrid Swallet cave, in March 2021, we started a new dig where we had found a strong draught from a narrow fault-controlled fissure that was partly filled with debris from the surface. It became known as Cockle Pot, unsurprisingly named for cockles excavated there. Initially it seemed we might be digging into a Romano-British midden; there are relics of this occupation nearby and a hoard of Roman coins had been discovered very close to this site. Soon, however, it became clear that the shells were dispersed in freeze-thaw textured till-cum-soil to at least 4 m below the surface. Further, there were other marine shells present showing that they do not represent any deliberate collection for food. The ground surface around there is littered with Devensian north-crop glacial erratics, but these are absent in the underlying cockle-containing fissure fill.

Figure 13. Cockle Pot fault-fissure sections (SS53065 91147; at 70 m OD) and representative marine faunal remains collected 1-4 m below the surface. These shells conceivably are some 0.5 million years old.

Figure 14. Probable course of the Anglian ice that delivered the marine shells to Llethrid. The pathway shown is notional and a narrow part of an extensive ice sheet advancing on a broad front. At that time, 450,000 years ago, the sea coast would have been far to the southwest of here, with relict marine sediments subaerially exposed to the advancing ice not only in the Carmarthen Bay area but also widely across the valley that would become the Bristol Channel. (Base image from EMODnet 2019).

Setting aside Noah’s flood, the shells (Fig. 13) can only have been delivered to Llethrid by the Anglian ice, which came from the west-northwest across Gower. Such ‘fossiliferous’ Anglian deposits are rare. Clearly the shell assemblage registers shallow marine to estuarine conditions, like those of the mouth of the Loughor Estuary and in Carmarthen Bay today. The Anglian ice must have picked up the material in crossing ancient equivalents of today’s deposits, but at a time when sea level would have been nowhere near there. The shells must record marine conditions that predate the Anglian glaciation and so could be some 0.5 million years old. They tell us that the Anglian ice crossed relict shallow marine to estuarine deposits that had been left high and dry when tundra and freezing conditions developed ahead of the glaciation.

Cave system formed under the Anglian ice

A new cave discovered

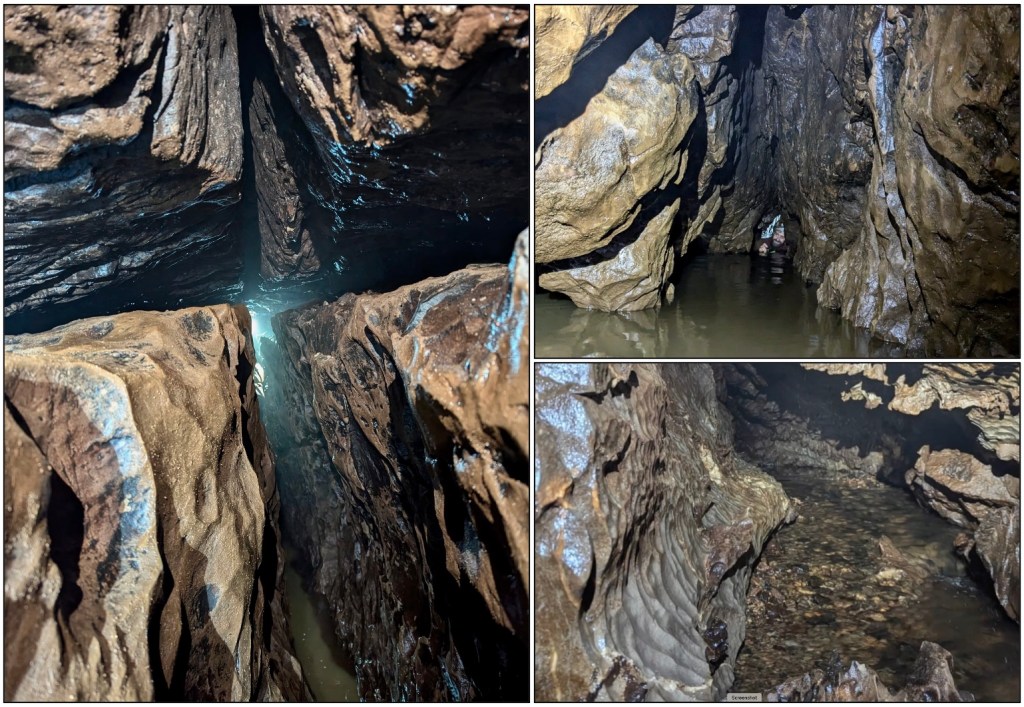

Ogof New Park, in north Gower, was ‘dug’ into and continuously ‘developed’ in 2024 by an intrepid team of caving friends, led by Andy and Antonia Freem. It is the first significant cave find on Gower in recent decades, at about 400 m long. It proved to be a serious and strenuous undertaking to penetrate fully, with its ‘difficult’ character proving to be a feature of scientific interest – as explained here (Figs 15-19). We currently do not know if it can be pushed farther. The target was to follow intermittent flood drainage within a large sinkhole-cum-collapse pit. Initial attempts to follow the sinking stream were thwarted by floods and wall collapse so that eventually a mostly debris-filled series of cracks in solid limestone was cleared and considerable volumes of rock broken out and removed to enable continuation downwards. At this early stage I decided that being fat was a great advantage so, while I could, I helped pull a few buckets up from the top of the ominously tight hole… Far better than the read below, the Youtube video ‘Discovering a new cave in Gower: Ogof New Park’ https://youtu.be/fZIL388uo9Q by Andy and Antonia is the best way to see the cave and its exploration; it includes appropriate credits to the entire team.

Geologically, the known cave penetrates northwards through successive beds in the middle part of the Carboniferous Limestone (British Geological Survey, 2002), while the stream itself emerges on the north Gower coast from the top of the succession, at Staffal Haegr (Fig. 22). The limestone beds, typically of metre-scale thicknesses and with some shaley partings, vary in original type and texture so that the nature of the passages and their styles of corrosion (wall dissolution) change down stream. Difficulty of access was, however, more or less physically unrelenting and required protracted dry conditions. Occasional floods from rapid rainfall runoff across the extensive catchment of impermeable glacial till lead to temporary pond development in the sinkhole and most cave passages clearly then fill to the roof, as marked by froth.

Figure 15. Drone-vertical view of the entrance shaft and hauling rig. This excavation-enlarged hole followed one of the many crevices that took flood water from across the floor and also in low banks of the host ‘collapse pit’, expecting it to become confluent with wider passages downwards. (For the record, I admit here that I thought it would not ‘go’. There were many setbacks, but remarkable camaraderie and perseverance paid off and happily proved me wrong.) Each step farther into the cave amounted to a breakthrough and despite persisting tightness of passage, commonly with obstacles broken out to get through, the hard labours did repeatedly access special spaces. The exceptional Birthday Passage (for Sarah) is beautifully ornamented, here (right) showing classic stalactites, stalagmites and flowstone-cemented cobbles, with crystal-rimmed pools and rare centimetre-scale cave pearls.

Figure 16. Most penetration farther into the cave involved extremely uncomfortable and tight-space writhing over and under and between unusually spiky, bladed and sharp-edged limestone flanges and spines. Progress typically involved breaking off blocking flakes and learning the body contortion required to get through ... hats off indeed to the larger team members! These characteristically sharp and tortuous limestone-surface forms of the cave are interpreted as reflecting the pronounced effect of a solutional (dissolving) process that readily occurs under an ice sheet, i.e., ‘mixing corrosion’ – as explained below. Further suggesting subglacial cave development, irregular roof-pendant limestone shapes, as seen in the lower two images, typically mark times when aggressive water was forced to flow along the roof contact because of sediment infill beneath. This upwards directed corrosion, called paragenesis, is common where caves are influenced by nearby glacial erosion that produces copious sediment, which can fill passages but then may be subsequently washed out.

Figure 17. The cave mostly lacks the classic rounded tubes that characterise continuous cave development beneath a more or less stable water-table, i.e., the phreatic phase of all-round wall dissolution. On the left the active (non-flood) stream follows a gravel bed in a narrow steep fissure dissolved along an initial steep fracture (joint), while limited dissolution has barely opened and widened the bedding discontinuity that crosses it at 90o. The ‘Canal’ (top right) was barely passable by ducking and in non-flood conditions probably registers a local (perched) water table that drains down slowly. Towards the current limit of the cave exploration (bottom right), the stream flows freely again where medium-sized wall scallops register moderate open-channel (vadose) water flow velocities, probably involving some mechanical bed erosion.

Figure 18. A classic feature of caves that are or were susceptible to periodic sediment infilling and then flushing out, is that speleothems (calcite formations) once formed on dry surfaces become corroded and vestiges of the passage-infilling sediment that became cemented to walls are now all that remains after the passages were mainly flushed clear of the sediment. The top image shows remnants of a drip pit that was carved into gravel, then calcite-cemented, and then eroded to leave the stuck-on assemblage where a large rock fragment later became trapped. The basal thin flow-stone reveals an earlier cycle of speleothem development and sedimentation. These are records, hard to read precisely, of marked ‘climate’ and sedimentation fluctuations in cave development, which are particularly characteristic of glaciated limestone terrains. Lower left shows flowstone that had draped a dry surface but was then undermined and left hanging by renewed limestone corrosion. Lower right shows a stalagmite that grew on a dry surface but was subsequently corroded by renewed overflow of aggressive water.

Figure 19. The cave preserves numerous examples of infill involving typical north-crop erratics (of the 23,000 year-old Devensian glaciation), here mostly coated in black manganese oxide and in places with sandy matrix. These show that the cave was developed largely as-is before the Devensian glaciation delivered this debris. The cobbles, many of north-crop quartzite, are jammed at various levels throughout Ogof New Park and, given the features suggesting subglacial development, prove its predominantly Anglian-age development. Given that we know that many Gower caves existed before the Quaternary Ice Age, we should anticipate that the pre-Anglian limestone landscape around here was already karst with sink-holes, collapse pits and underground conduits, but the extraordinarily tight and gnarly New Park system seemingly requires the special circumstance of having mainly formed under thick Anglian ice.

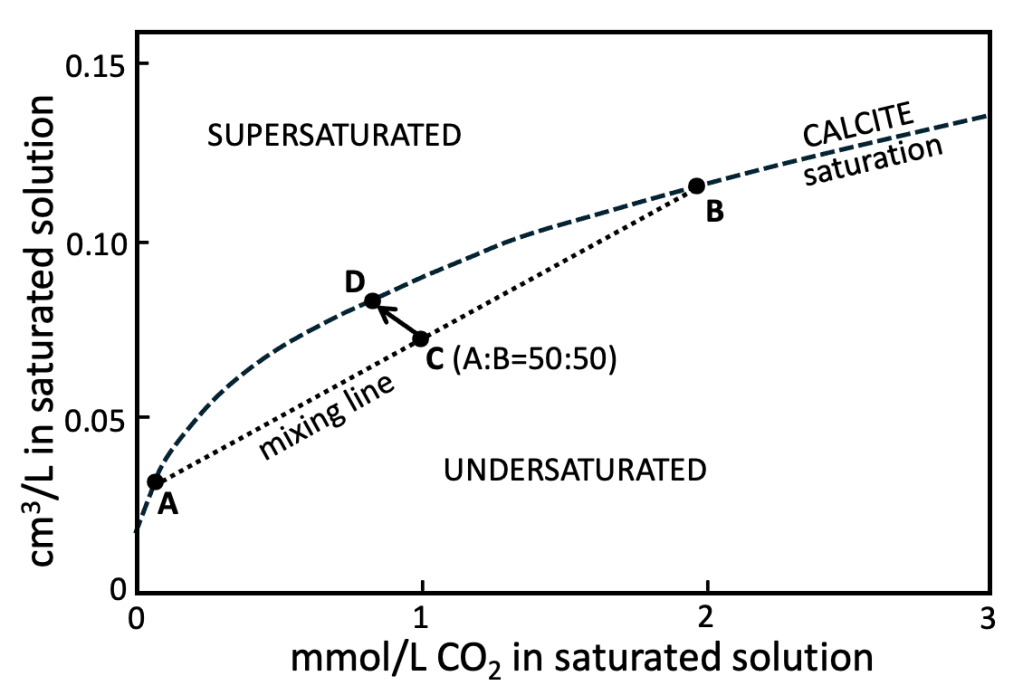

Mixing corrosion explained. Bögli (1964, 1980) recognised that because the saturation of calcite in mildly acid aqueous CO2 solutions is non-linear, mixing of two differing saturated solutions would produce an unsaturated mixture that could then be ‘aggressive’ and cause further calcite corrosion. Figure 20 shows that, for example, mixing of solutions A and B – in this case in equal amounts 50:50 – would create the solution C that could then dissolve more calcite until reaching saturation at D. The mixing corrosion phenomenon is well known at and downstream of the confluence of underground streams with differing chemistry and it can be favoured especially beneath an ice sheet that feeds diverse waters widely down into karst substrate with confluent drainage.

Figure 20. Mixing corrosion as explained by Bögli (1964, 1980).

The case for cave development under the Anglian ice sheet

Ogof New Park (ONP) contains abundant Devensian erratic material, evidently jammed into pre-existing voids and although widely washed out it forms most of the present stream-bed sediment. The inner flanks of the collapse pit into which the ONP stream drains are plastered in Devensian till and the geophysical survey undertaken above the cave (Figs 22 and 23) shows thick parts of the Devensian recessional Welsh Moor – Oldwalls – Fairy Hill moraine as part of the till cover. Logically, although still an active cave system, ONP predates the 23,000 year old cover of the Last Glacial Maximum.

In terms of maximum age of development of through-going conduits, sinkhole-drain systems like ONP most probably formed initially in the marine planation surface that was cut in the Late Pliocene, before onset of the Quaternary ‘Ice Age’ 2.58 million years ago. There is no evidence of glaciation on Gower before the Anglian event at 450,000 years ago, so one may imagine a 2-million-year evolution of a karst surface with subterranean conduits during that time of successive glacial and interglacial episodes. Ogof New Park appears to record an original three-dimensional fracture and bedding network that was linked to the karst surface via several routes, the main ones draining the main local collapse pit. Its main development then appears to have occurred beneath the Anglian Irish Sea Ice Sheet, with only minor more recent modifications since the Devensian glaciation.

Here it is proposed that Ogof New Park is a distinct ‘sinkhole-drain’ type of cave and that it is the youngest of three distinct generations and types of Gower cave.

1. Latest Triassic caves, about 200 million years old, represented by sediment-infilled phreatic tubes on Worms Head and Oxwich Point. The extensional faults of the Late Trias did not develop solutional caves because there was practically no persistent water in the desert environments of that time (there were flash floods and waddis). Only when sea levels rose ahead of the Liassic marine transgression did trapped meteoric ground water form stable water tables and thus caves, where fossils of herbivorous reptiles are found now in identical settings in South Glamorgan (Fig. 21) and farther east (Mendips).

Figure 21. Occurrences of caves known to have formed at the end of Triassic times, with the Worms Head locality shown as a red star and previously identified sites in green. Key to appreciate here is that despite open faults forming in Late Triassic time, dissolutional caves did not form as there was barely any persistent water in the desert environments. The coincidence of herbivore fossil remains in karst caves shows the end-Triassic development of both vegetation and water tables, held in the ground by advancing sea level just ahead of marine conditions.

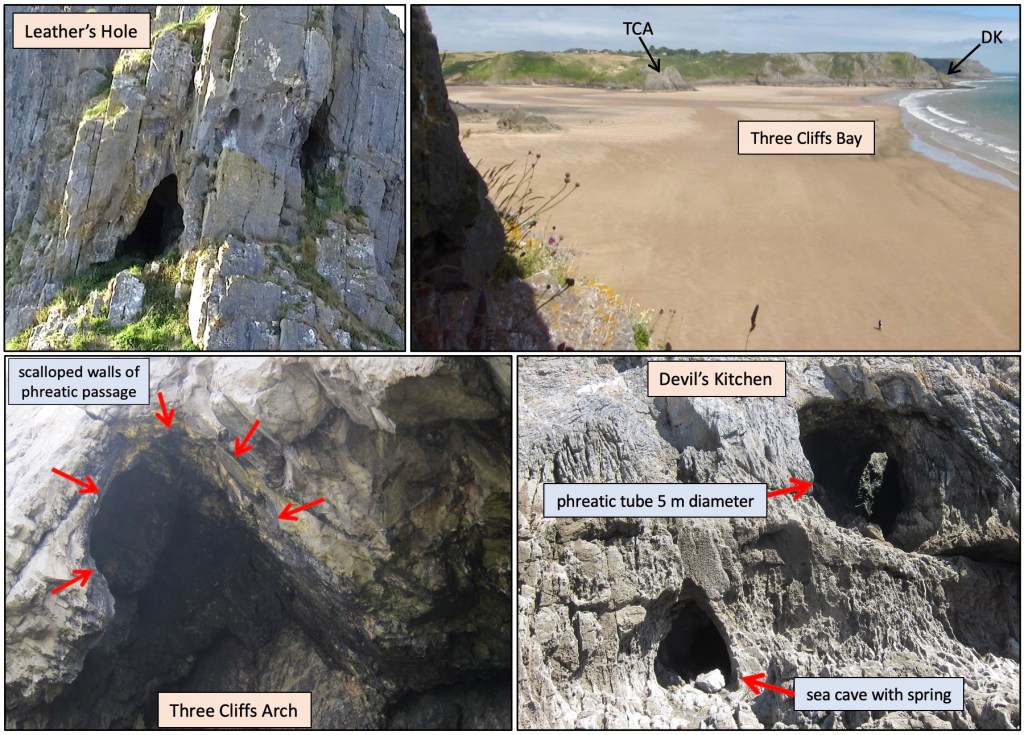

2. Classic limestone-massif caves. The majority of known human-penetrated and cliff-exposed caves are of this type, initially largely phreatic. These have been developing ever since the Gower limestones were first exposed by Paleogene-Neogene uplift and, as readily deduced, must have been forming at least 10 my ago. Llethrid, Tooth and Ogof Ffynnon Wyntog are well known examples with long histories, but other examples are those exposed in cliffs today, as at Leather’s Hole, Three Cliffs arch, Devils Kitchen and Bosco’s Den.

3. Sinkhole-drain caves are the youngest caves, of Quaternary age, Ogof New Park (ONP) being the prime example, but probably also the drains at Freedown, Llwyn y Bwch, Moormills and Caswell Valley. These formed initially in the Late Pliocene marine planation surface and on the basis of ONP were significantly developed by the Anglian glaciation of 450,000 years ago. (Possibly also Stembridge, Bovehill Pot, Hardings Down…. most barely penetrable, except for the potholes).

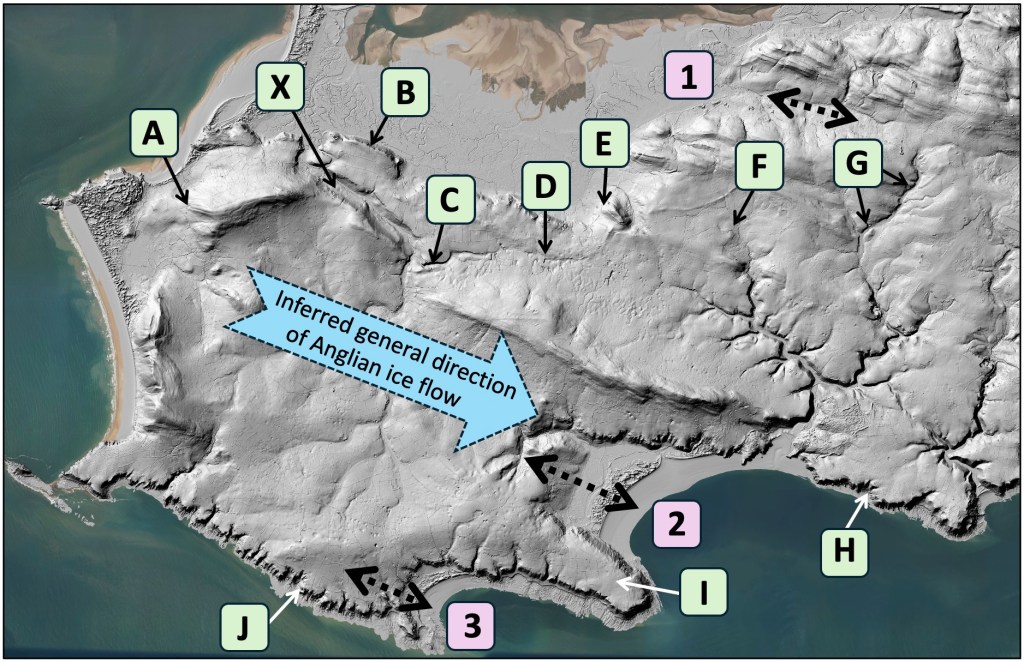

Anglian landforms on Gower

The following points are speculative, some extremely so. They arise from a long-term preoccupation with development of the Gower landscape, and in particular with features due to the Devensian glaciation. The latter glaciation widely destroyed or obscured pre-existing Anglian features, but it cannot explain everything seen. What follows is a list of some of the previously unexplained features that would be quite consistent with passage of the Anglian ice over Gower. We might reasonably assume that here the Irish Sea Ice Sheet would have been 250-300 metres thick during its maximum advance into what is now the Bristol Channel, and ‘warm-based’, i.e., not frozen to the ground and with abundant liquid water at its base.

Figure 34 (Base image: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/). A. The southwestern shoulder of Llanmadoc Hill is a steep slope without any obvious geological cause, possibly over steepened by ice from west-northwest. B. The area inland from the cliff tops (Tor-gro) steepens up towards northeast, rather than being a uniform gently inclined marine-cut platform as occurs elsewhere. Ice constrained to ascend from Carmarthen Bay and flow between here and Llanmadoc Hill may have eroded the less robust limestones beneath the cliff-forming Oxwich Head Limestone (see panel below).

C. Melins Lake subglacial channel cut in solid rock with misfit stream (see section below). D. Ogof New Park subglacially formed cave system (see previous section). E. The southwestern side of Cilifor (hill fort) is a steep slope without any obvious geological or hydrological cause; although sandstone beds occur in the ridge crest the main slope and ‘valley’* are in relatively soft mudstone: possibly over steepened by ice from west-northwest. *(The southeast end of this valley is partly filled with the Devensian Welsh Moor recessional moraine). F. Deep, narrow gorge cut in mudstone capped by Devensian till. As at G, this cutting through a barrier of relatively soft rock has no obvious original headwater drainage and is currently fed from a minor spring (mapped as ‘rises’). It is possibly a subglacial streamway. G. Gorge cut through sandstones and mudstone, currently with a misfit stream meandering in Devensian glaciofluvial outwash (Kokelaar 2021, p. 103). Devensian till apparently fills a pre-existing rocky channel, which possibly is a subglacial streamway. H. Ice-sculpted sea cliffs (see section below). I. Oxwich Point differs from the gently sloping marine platform elsewhere in being a ridge that slopes evenly on either flank, to southwest and northeast. It is draped in Anglian till and conceivably was shape-modified between thick ice on either flank flowing east-southeast. J. Ice-sculpted sea cliffs (see section below). X. This most striking of channel features was probably initiated under the Anglian ice but is, however, known to have been a drain from beneath the Devensian ice (Kokelaar 2024) so that its original form and course remain a mystery (compounded by a buried channel towards Landimore!) .

It is a coincidence that the folded rock layers of Gower trend (strike) generally west-northwest, which on the evidence from erratics, and cockles, is roughly parallel to the inferred direction of flow of the Anglian ice sheet from Pembrokeshire over Gower. There is absolutely no direct evidence in respect of the following points 1-3 (see Fig. 34), but the inferences are physically plausible and perhaps stimulate a little thought regarding possibilities in the evolution of our landscape.

1. Morlais River valley is floored by relatively soft and erodible Middle Coal Measures mudstones and is flanked by ridges largely composed of robust sandstones. The river clearly is a misfit (too small) as there is no obvious drainage that could have carved the valley. The valley and its flanks are draped by Devensian till and are inferred to have been exploited and partly shaped by the passage of Anglian ice. 2. Oxwich Bay occupies a syncline (down-fold) where relatively soft and erodible mudstones of the Marros Formation lie between more robust, cliff-forming limestones. The syncline plunges southeast, so the mudstones die out to northwest and get deeper to southeast. The bay has long been interpreted as reflecting preferential erosion of the mudstones, but here it is speculated (only) that the Anglian ice must have contributed to the depth of the embayment. 3. Port Eynon Bay, just as at Oxwich Bay, is underlain on its southwest side by a narrow folded layer of Marros mudstone, so that the same speculation is made for this bay too, i.e., ice is likely to have eroded down beneath it.

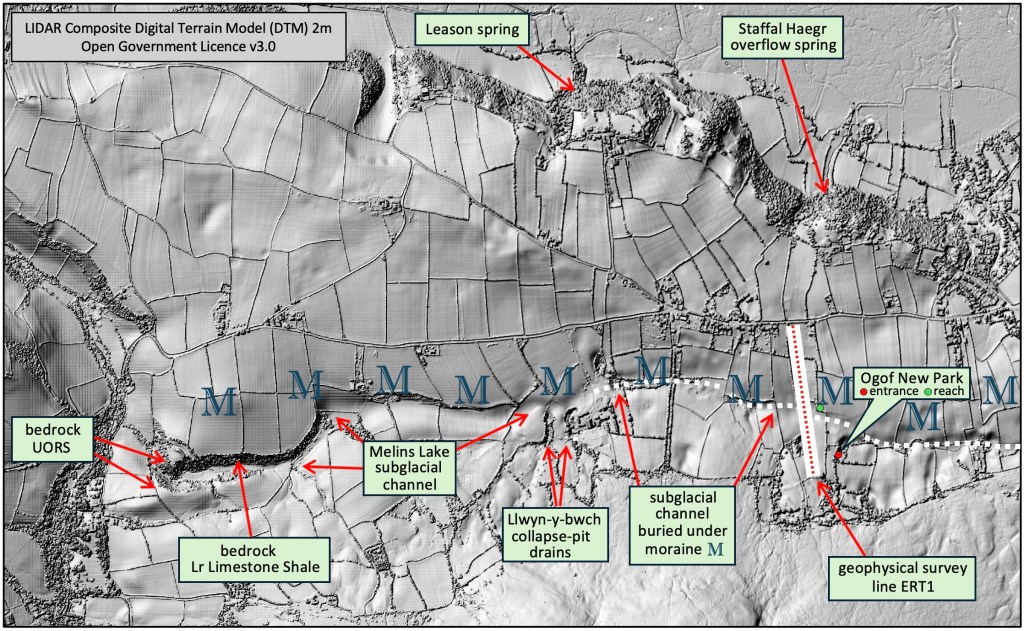

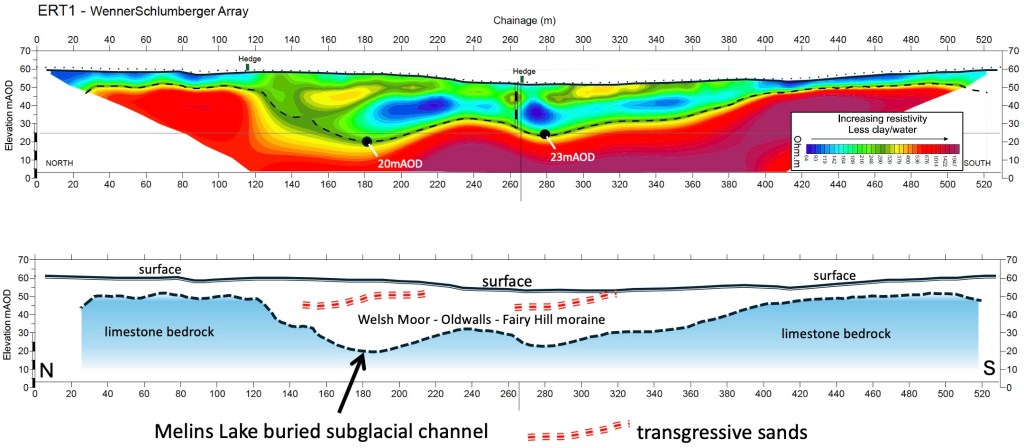

A prominent sub-glacial channel

The most prominent topographic feature on Gower formed during the Anglian glaciation is the Melins Lake channel (Fig. 22). It is traceable for almost 3 km, as a striking gorge cut in solid bedrock towards the western end while it becomes partially buried and obscured by the Welsh Moor – Oldwalls – Fairy Hill moraine towards the east. Almost certainly it would have continued northwest via the valley of the Burry Pill, but this was exploited subglacially during the later, Devensian, glaciation, so that its earlier form is unknown. Melins Lake is the name of the misfit present-day stream on the OS Six Inch map, dated 1888-1915. Lake is an old term for stream. It presently drains westwards, but the original flow direction is uncertain since under ice that is 100s of metres thick there will tend to be a water table within it and the hydraulic gradient can cause basal water locally to flow up hill.

Figure 22. Trace of the Melins Lake subglacial channel eastwards from fully exposed in bedrock to substantially obscured by till and the Welsh Moor – Oldwalls – Fairy Hill moraine (letters M) above the Ogof New Park subglacially formed cave system.

Figure 23. View towards east, the gorge is cut in solid rock with the Melins Lake stream clearly a misfit (i.e., not of a scale sufficient to have eroded the channel feature).

Figure 23. Geophysical resistivity survey across the Melins Lake subglacial channel where it is largely infilled by thick deposits of the Devensian recessional Welsh Moor – Oldwalls – Fairy Hill moraine. The oblique features shaded yellow within the infilling moraine are sandier parts that as the moraine was built up advanced (transgressed) farther southwards, i.e., upwards left to right in this section. The survey and processing were kindly provided by friends Alex Lewis and Kathrin Zorn of Terradat (UK) Ltd.

Ice-sculpted cliffs

Figure 33. South Gower limestone cliffs predominantly of well-bedded High Tor Limestone overlain by well-bedded Hunts Bay Oolite. Top. Common Cliff towards Blackhole Gut (SS44701 85308). Strata dip inland at about 45o. Middle. Heatherslade towards High Tor (SS55553 86965). Strata dip seawards at 66o-38o. Bottom. Ice-sculpted arête below West Cliff, Southgate (SS55133 87218). Strata dip seawards at 66o.

The key features shown are that the cliff slopes are more or less smoothly rounded, cutting across and barely reflecting the limestone bedding while widely shallowing in slope towards the low-tide to shallow-offshore shelf/platform. In the bottom image, two ice-sculpted slopes intersect to form a well-defined arête that drops from about 60 m to 20 m OD. The profiles are smoothest where the limestone beds are thin, thicker beds commonly forming ribs or steps. The smooth slopes are unlike those where beds are thick or where nearly horizontal or very steep, in which cases steep cliffs tend to reflect marine erosion and collapse, and/or plucking by ice. These smoothly rounded slopes are taken to record effective abrasive erosion, or sculpting, that occurred beneath the thick Anglian ice sheet.

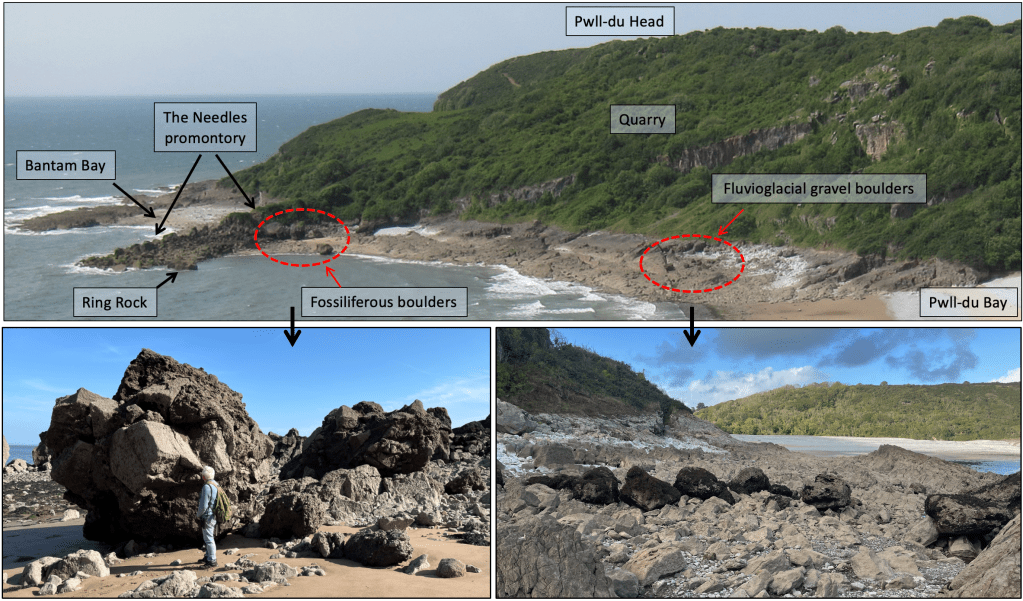

Enigmatic boulders at Pwll-du

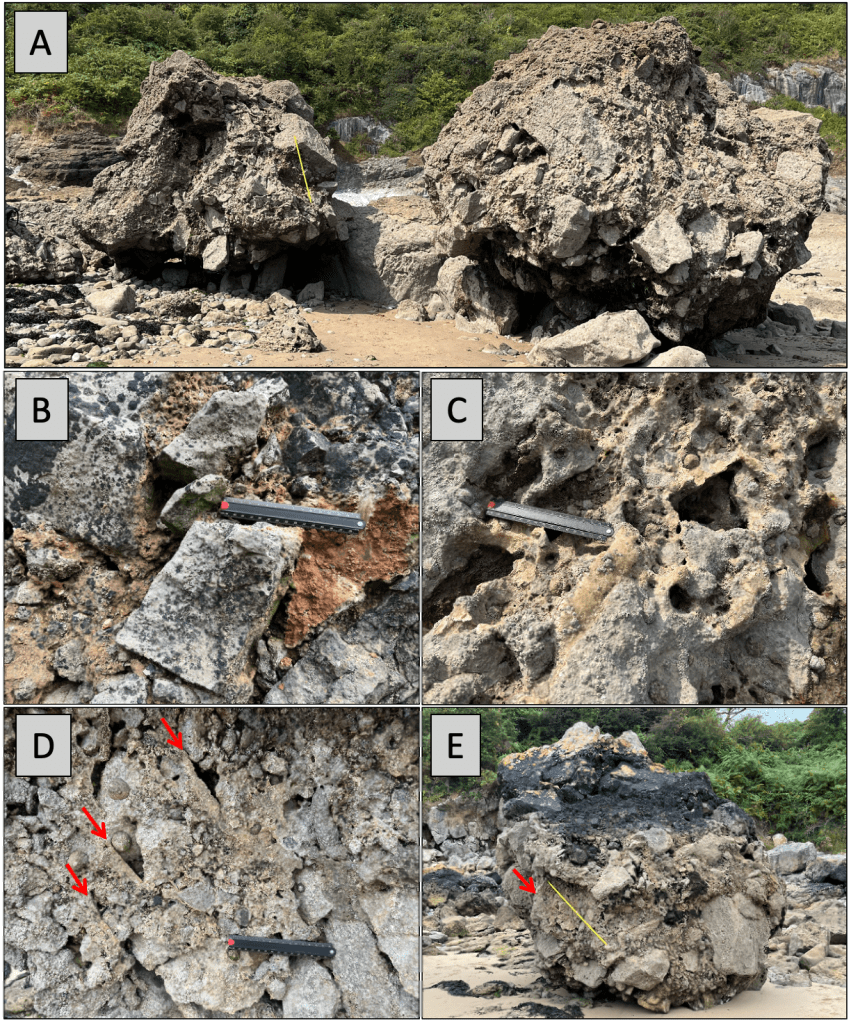

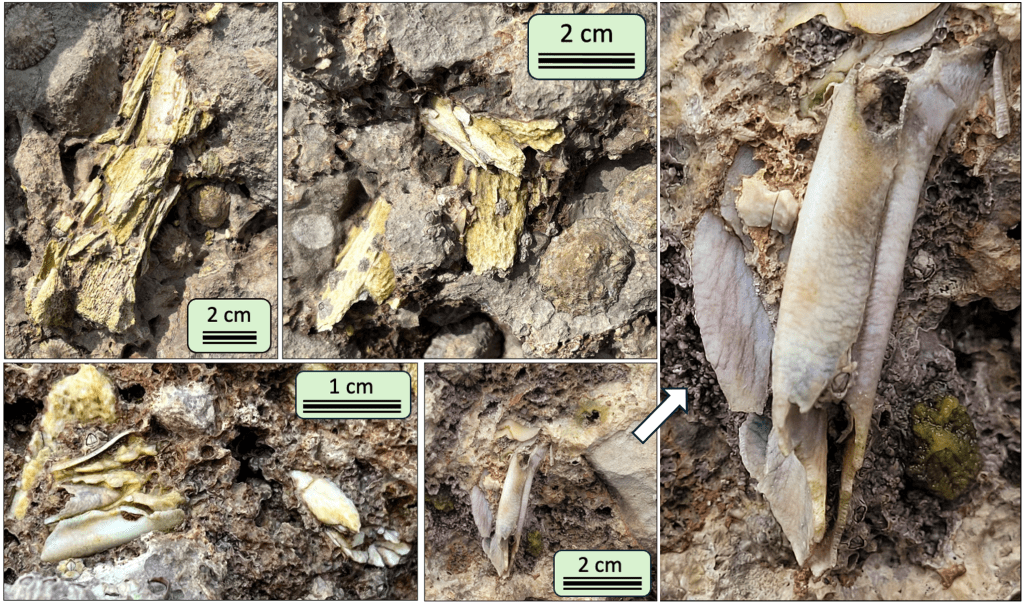

On Thursday 26th September 2024, at 11.05, I received an email from Professor Paul Griffiths, who asked if I knew anything about a small cluster of boulders in Pwll-du, largely covered with seaweed and composed of “hard conglomerate … not noticed on any other beach…”. At the time I was starting out on the Anglian glaciation of Gower and I really had nothing to offer about the boulders. I definitely had no idea that Paul’s findings would lead us to appeal to just that cold episode. Narrowly missing April Fool’s Day, Paul at last showed me his discoveries on 31st March, 2025 – a cluster of boulders of rock I had never seen before, and a fossil in different huge boulders close to the Needles promontory.

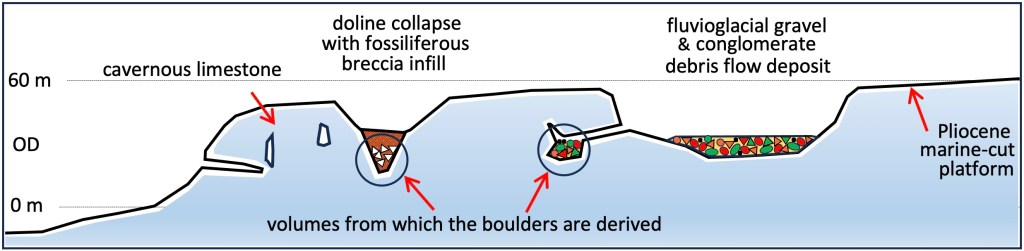

Perhaps best shown via pictures, what follows is an inexorably bizarre series of inferences that together paint a picture of a Gower karst landscape that occurred during the melting back of the Anglian ice sheet (deglaciation) and, seemingly, then evolved to post-glacial milder conditions. Cutting to the chase, the seaweed-obscured boulders appear to be of energetically emplaced fluvioglacial gravel originally preserved in a karst depression or cave, while the fossiliferous boulders record a limestone karst pit collapse (a doline) involving one or more medium-sized mammals, followed by speleothem deposition.

Figure 24. West side of Pwll-du Bay showing the separate locations of the different boulders discussed here. The western neck-end of the Needles promontory and the nearby cliffed back of Bantam Bay are bedrock limestone riddled with solution tubes (small caves) and crevices, locally with linings of cave-deposit speleothems, particularly so-called flowstone. Not at first obviously related, this cavernous bedrock, the fossiliferous boulders and the cluster of fluvioglacial gravel boulders can be interpreted in terms of an ancient karst terrain …

Fluvioglacial gravel boulders

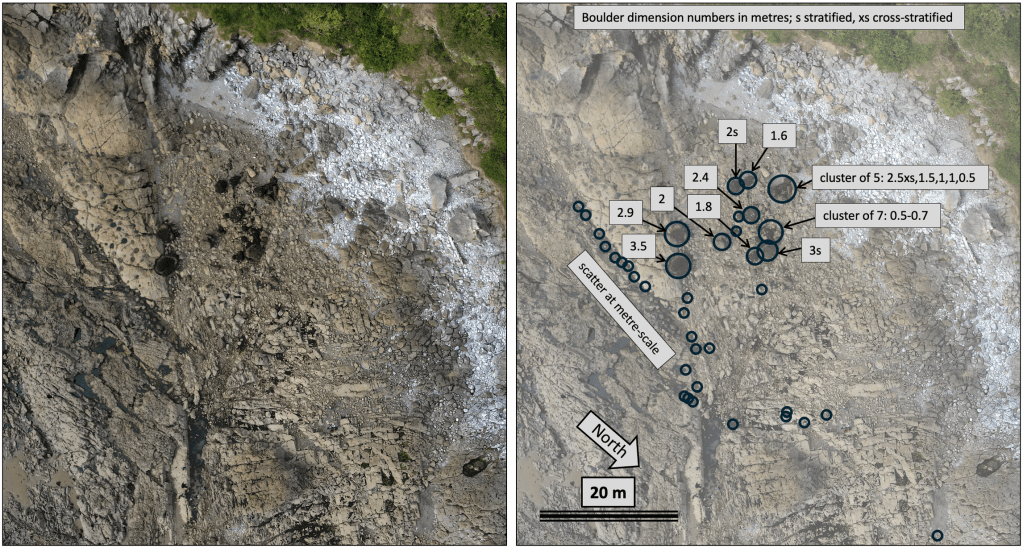

Figure 25. Drone photo vertical view of the mainly seaweed-clad gravel boulders, with overlay map (right) showing the close clustering of this unusual rock, with some of the larger dimensions of them given in metres. The close grouping and limited scatter of smaller fragments suggest that the boulders are parts of an original singular occurrence somehow isolated and stranded on the modern limestone beach platform. (Drone photo courtesy of Andy and Antonia Freem).

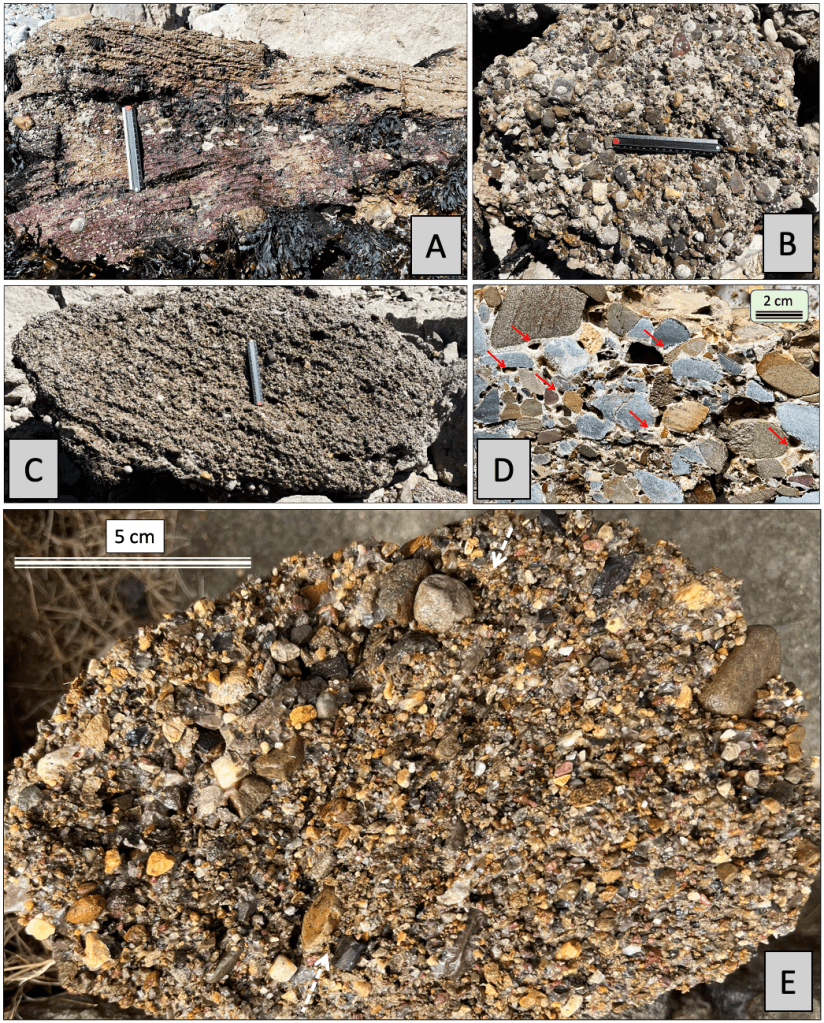

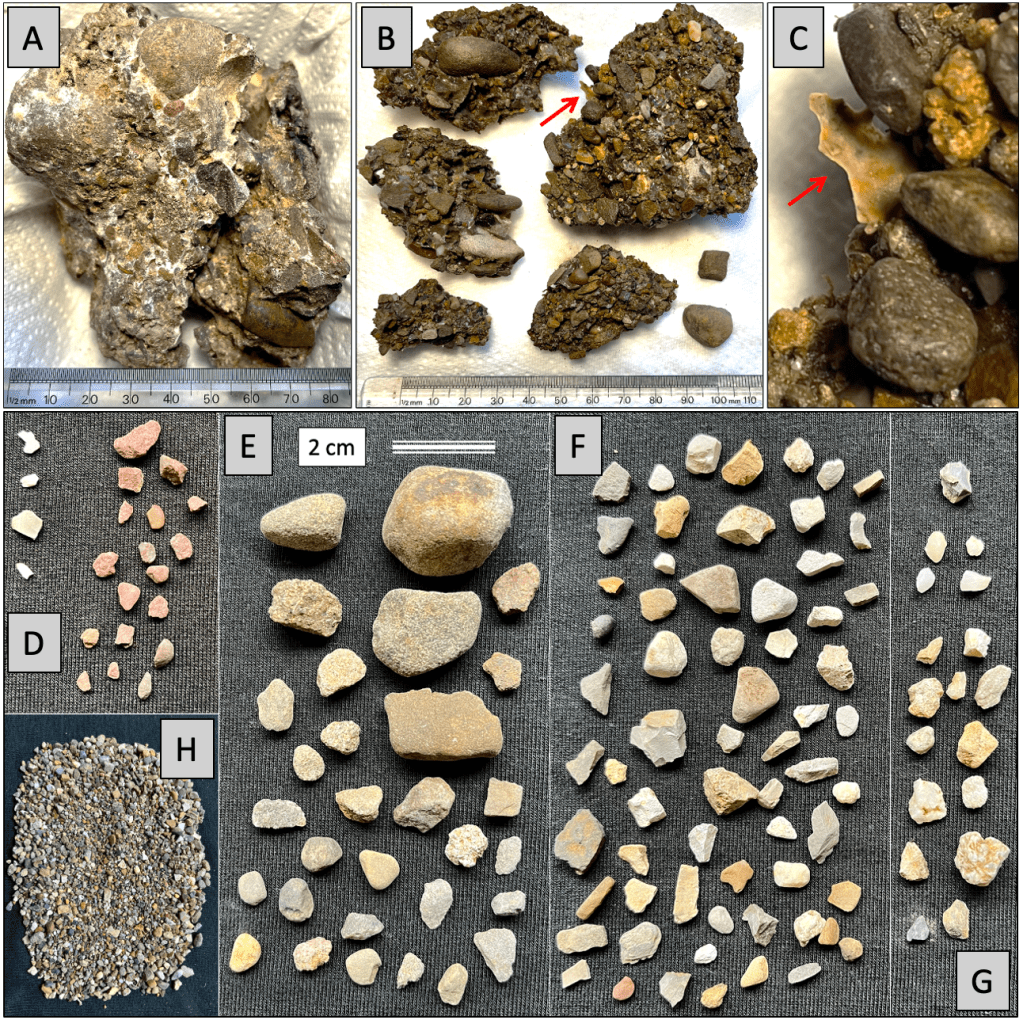

Figure 26. A-C. Natural surfaces of the enigmatic boulders; ruler is 15 cm. A. Uppermost parts of the deposits in places are coarse, pebbly sandstone, here showing cross-stratification indicative of deposition from a moderately strong flow of water. B. Weakly stratified, poorly sorted pebble gravel-conglomerate. C. Moderately stratified and weakly cross-stratified pebbly gravel. D. Cut face of pebbly gravel showing calcite cement partially infilling original voids (red arrows) between pebbles mostly of Pennant sandstone. Calcite clearly grew from pebble surfaces, in many places leaving crystal-lined voids. Quite speculatively, this porosity, peculiar to the these enigmatic boulders, may be how seaweeds colonise the surfaces unlike elsewhere on adjacent impervious limestone surfaces. E. Acid-etched broken-cobble surface, showing poorly sorted gravel and pebbly gravel with indistinct stratification (parallel to the line between white dashed arrows). The mix of rock types and of rounding versus angularity is shown in Figure 27 D-H below, which is of this sample with its calcite cement completely dissolved away.

Figure 27. A-C. Calcite-cemented pebble conglomerate with partially dissolved counterparts showing well-rounded pebbles with embedded organic ‘flake’ (arrows) taken to be (insoluble) bone or tooth material, primarily calcium phosphate as the mineral apatite or hydroxyapatite. D-H. Completely disaggregated constituents of the rock shown in Figure 26 E; scale bar applies to D-G. D. Insoluble organic mineral flakes (left) and assorted red sandstone and siltstone fragments (right) with variable angularity/rounding, probably mostly Old Red Sandstone. E. Mostly Pennant sandstone including well-rounded pebbles but also mostly smaller angular fragments. F. Assorted fine-grained sandstone and siltstone including all variations from well-rounded to highly angular; several of the rock types are not recognised and the sources of all are unknown. G. Fragments of chert (possibly flint at top), quartz-sandstone and vein quartz. H. Sand and gravel remainder of sample.

The two figures above show the make-up of the enigmatic boulders. The rounding of the pebbles and some small pea-sized gravel fragments requires energetic fluvial action, while the extreme angularity of the thoroughly admixed material is characteristic of the freeze-thaw (thermoclastic) fragmentation that is typical of periglacial areas. The poor sorting and indistinct cross-stratification indicate rapid, concentrated sediment flow while the cross-stratification near the top is more like that developed in energetic rivers. Hence the boulders are interpreted as composed of fluvioglacial deposits that were rapidly emplaced from flood-like flows that picked up surface-weathered material and were capable of carrying abundant large fragments. Late-stage aqueous flow transported and finally deposited the gravel and coarse sand. A few angular blocks of limestone occur near the inferred top within the deposit and, as foreign material, appear to have been ‘accidentally’ incorporated in the flood-like flow.

Interim interpretation. The enigmatic boulders seem compositionally unique and the origin of their fragments is unknown, except that the abundance of Pennant sandstone fragments requires derivation from the north, somewhere in the broad outcrop within the South Wales Coalfield. The boulders themselves appear to have survived the attrition, abrasion and dissolution that typically affects the local coastal limestones, conceivably because they are largely composed of resistant (insoluble) Pennant sandstone. The close grouping and similarity of the boulders suggest they were once a continuous deposit that became cemented with calcite, which partially filled original pore spaces (holes), before it was broken up.

There is no indication of original surrounding contacts of the gravel-conglomerates and the inclined dips of the bedding within them shows that they have been freely rotated, although the large boulders on the northwest side have similar dips and crude stratigraphy. It is inferred that the deposits are of material that rapidly flowed into an underground cavern where it was trapped. The cross-stratified ‘top’ of the deposit has no different material on it, but instead indicates vigorous aqueous to waning-flow sedimentation suggesting deposition in an enclosed space not directly leading to the surface (see explanation of the other boulders).

Fossiliferous boulders

Close to the Needles promontory there are several enormous boulders, the main feature of which is their content of large, angular blocks of limestone. Cutting to the chase immediately, these are typical of cavern or doline (pit) collapse breccias, with a doline favoured owing to evidence of connection to the surface in the form of mammalian bone remains. Rather like the other boulders discussed above, these form a localised scatter not obviously related to the adjacent Pinnacles, which is a naturally broken-up part of the quarried limestone layer, nor are they obviously derived from nearby cliffs. Like the fluvioglacial deposit boulders, these seem to rest near to where they were originally formed but somehow have become isolated now from the limestones that once must have contained them. This problem is leading to what is now recognisable as a massive amount and rate of limestone mass removal by dissolution and mechanical erosion through time, which is explained more fully in a separate section below.

Figure 28. (Scales are a 1 m measure and 15 cm ruler). A. The boulders comprise a jumble of angular blocks of all sizes widely up to around 1 m in diameter. Original spaces between the blocks are in some parts infiltrated by red-brown (limonitic) silt-sand sediment (B), and elsewhere are heavily cemented together with calcite (C), locally showing crystal-lined voids with originally horizontal floors (red arrows in D and E). Patches of calcite flow-stone occur locally in voids.

Figure 29. Bone and possible tooth fragments occur in several boulders, appearing to have been broken before and/or during the breccia collapse since they are randomly mixed with the rock fragments. The fossils are probably of one or more medium-sized mammal, suggesting that the surface environment was to an extent vegetated and hence probably post-glacial and relatively warm. The warm interglacial episode following the Anglian glacial time is referred to as the Hoxnian, dating around 425,000 years ago. Flowstone sampled by this author in Leather’s Hole in Great Tor gives a robust age of 425 ka, which would fit with the calcite cementation and flowstone abundant at this similarly set locality….

Figure 30 below offers a somewhat bizarre but self-consistent explanation of the Pwll-du boulders. The inference of a fluvioglacial debris-flow deposit is absolutely consistent with the discovery of such material that penetrated the caves – Tooth Cave and Barns Cave – at the top of Green Cwm, by Llethrid (Kokelaar 2021 pp. 124-149). This event was related to a catastrophic flood of glacial outwash that occurred during retreat of ice of the Last Glacial Maximum (Devensian). It flooded down the pre-existing valley, diverting its river and penetrating some 1 km underground. There is no (known) relic of such an Anglian-age debris flow in the local terrain, but this would have been thoroughly reworked and eroded away since 450,000 years ago. Thus the boulders found by Paul Griffiths and “not noticed on any other beach”, seem to be an exceptional remnant from the Anglian glacial recession.

Figure 30. Cartoon (not to scale) explanation of the origins of the enigmatic boulder of Pwll-du. It has to be inferred that ‘normal’ processes of erosion of the limestone – dissolution and abrasion – removed the containment of the differing boulders, probably in the process lowering them to the modern beach platform and causing limited breakup. Although this seems hard to imagine, in the following section the scale and rate of loss of limestone by erosion are revealed as remarkable, so the inference here is quite reasonable.

We know that many Gower caves have existed from long before the Ice Age, so here we may consider a pre-Anglian karst terrain, widely planed by the Late Pliocene seas some 3 million years ago and with valleys and dolines or sink holes. This landscape of platform, holes and cliffs necessarily will have been modified by the passage of the Irish Sea Ice Sheet, probably of several hundred of metres in thickness. The Pwll-du boulders perhaps provide a glimpse of conditions during retreat of that Anglian ice.

More….

Missing limestone – a lot of it

It is extremely difficult to appreciate fully how much rock is missing from above the surface we are so used to seeing today. In the book (Kokelaar 2021) I explain that we must be missing at least a one kilometre thickness of rock that once overlay our Gower of today, due to uplift with erosion since some 60 million years ago. But let us focus here on what our modern limestone cliffs and platform of the peninsula tell us.

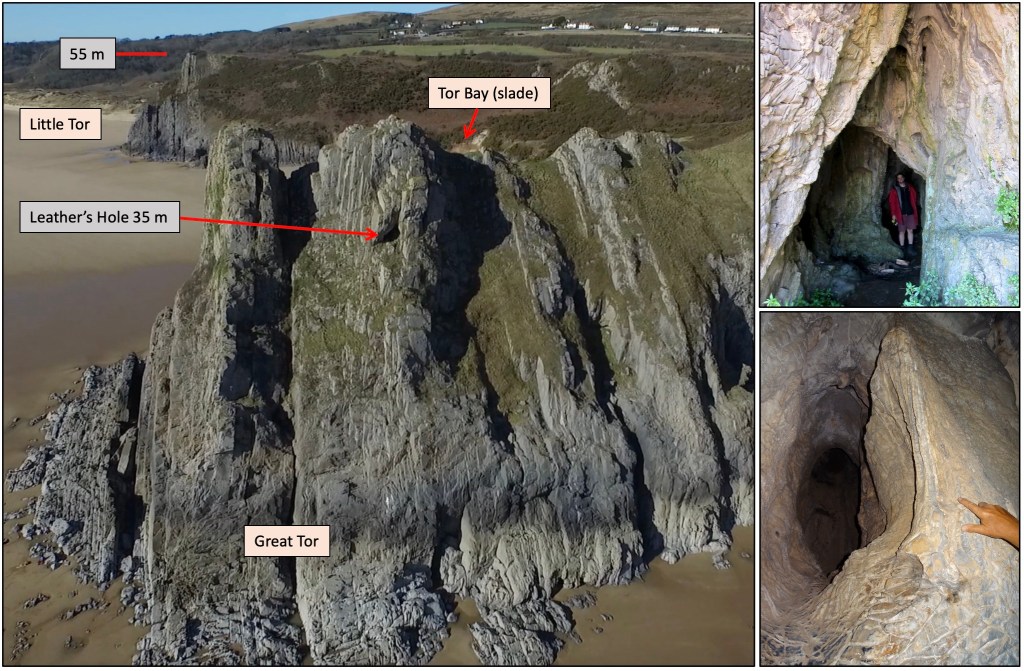

Gower’s main extensive active cave systems, Ogof Ffynnon Wyntog, Llethrid and Tooth Cave, all have considerable reaches of passage that formed beneath a water table – the phreatic rounded-tube-forming phase. Most telling perhaps are the numerous occurrences exposed in our cliffs of phreatic tubes that have drained long ago, truncated in open space and inactive. Using Leather’s Hole in Great Tor as an illustration (Fig. 31), we can be sure that most of its passages originated beneath a water table. But, obviously, the cutting of the cliffs, which formed between valleys, or slades, on either side must have drained that water. We know that the slades were ‘beheaded’ by the Late Pliocene marine erosion of about 3 million years ago, so the slades that did the draining must have formed earlier… In this way we deduce that the time when the water tables were held within a limestone massif, necessarily before the slades were cut, was probably at least 10 million years ago.

Figure 31 alone ‘speaks’ of a huge amount of missing limestone of the original water-holding massif, but when viewing from Leather’s Hole towards the east (Fig. 32 top), the missing amount becomes awesome.

Figure 31. Leather’s Hole comprises a small network of caverns and tubes that now emerge in the cliff faces but must have formed within a water table. Tor Bay is a slade (valley) the sides of which are truncated at about 55 m OD by the Late Pliocene marine platform, which formed some 3 million years ago.

Figure 32. Top right is the view from the larger entrance into Leather’s Hole across to Three Cliffs and the cliffs containing Devil’s Kitchen. All were once embedded in a continuous limestone massif that was deeply eroded to form the present 60 m OD platform, as well as the existing sea cliffs and the valley that emerges at the bay. Bottom right neatly shows a characteristic near-cylindrical phreatic tube, formed beneath a water table, in contrast to the sea cave with typical A-form owing to most mechanical wave-related erosion being lowest down.

The arch (through passage) in Three Cliffs retains part of a large phreatic tube (Fig. 32) while farther east Devil’s Kitchen is a large tube that turns from vertical downwards to emerge horizontally in the cliff face, and there are numerous other similar relics along that coast. One may begin to grasp the scale of erosional removal of the limestone when considering the view from Leather’s Hole across the bay to Three Cliffs and the cliffs around Devil’s Kitchen (Fig. 32), and then realising that these caves were all once embedded within an original continuous limestone massif. Not only was the limestone cut by the valleys and truncated by the marine platform we see, but also the present cliffs are remnants of the pre-existing massif. So, we now observe the end product of massive removal of limestone during 10 million years or more – a rate we may only vaguely begin to imagine.

But, for our Pwll-du boulders we know that they were once material embedded in cavernous limestone less than 450,000 years ago. The evident isolation of the boulders in Pwll-du then is only a minor reflection of the striking erosional cutting that was a very much longer-lived process. The Pwll-du cases give us some insight into what can happen in less that half a million years… Most conservatively, taking the minimum limestone cliff retreat to leave the enigmatic boulders, the coastal erosion back to form the present platform and cliffs – in this bay – is some 100 m.

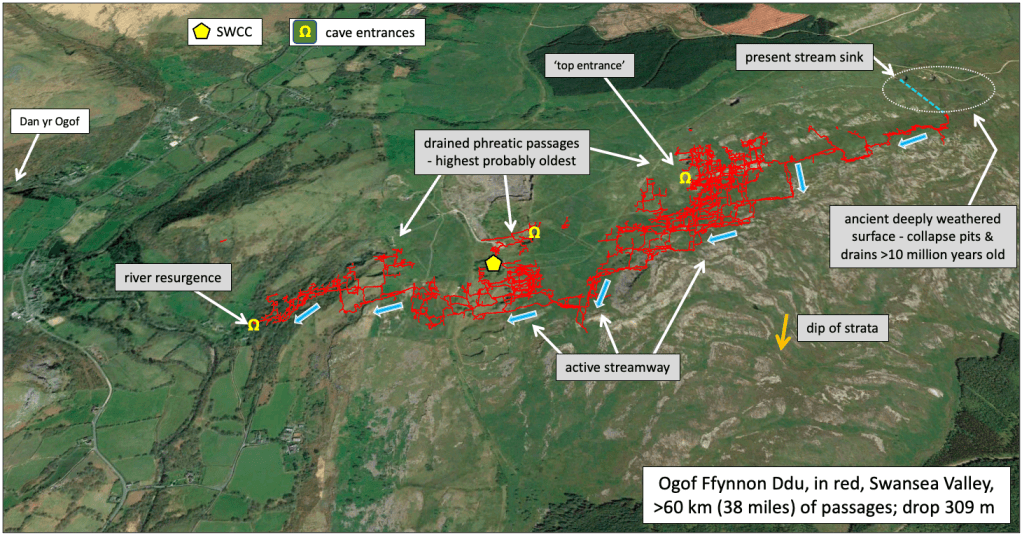

Understanding Gower’s missing limestone by looking at a Swansea Valley cave system

Here I try to demonstrate that vast amounts of limestone have been eroded away from previously existing high ground during the marine planation of Gower ~3 million years ago, and also that the comparatively recent (Holocene; 11,500 years until now) rise in sea level has caused access loss at low levels where significant cave rivers originally drained freely. To do this I use the northern outcrop of the same Carboniferous Limestone unit where uplift-related erosion of upper parts remains clear to see (not affected by marine planation), and where sea level has not advanced to cover and block cave exits. The case centres on Ogof Ffynnon Ddu (OFD; Cave of the Black Spring) on the east flank of the Swansea Valley, opposite the well-known major cave Dan yr Ogof.

Cavers, principally from the South Wales Caving Club, have over many years thoroughly surveyed OFD, fixing its known vertical extent at 309 m. Its lowest levels, from sink to resurgence, are occupied by the active streamway and its tributaries, which have long abandoned the upper passages they once occupied. ‘We’ used to think that the cave mainly developed during and since the past Ice Age (Pleistocene 2.58 million years), but the uplift and erosion governing its formation have occurred over 10s of millions of years (Kokelaar 2021, e.g., pp. 14-15). This is plainly evident on Gower…

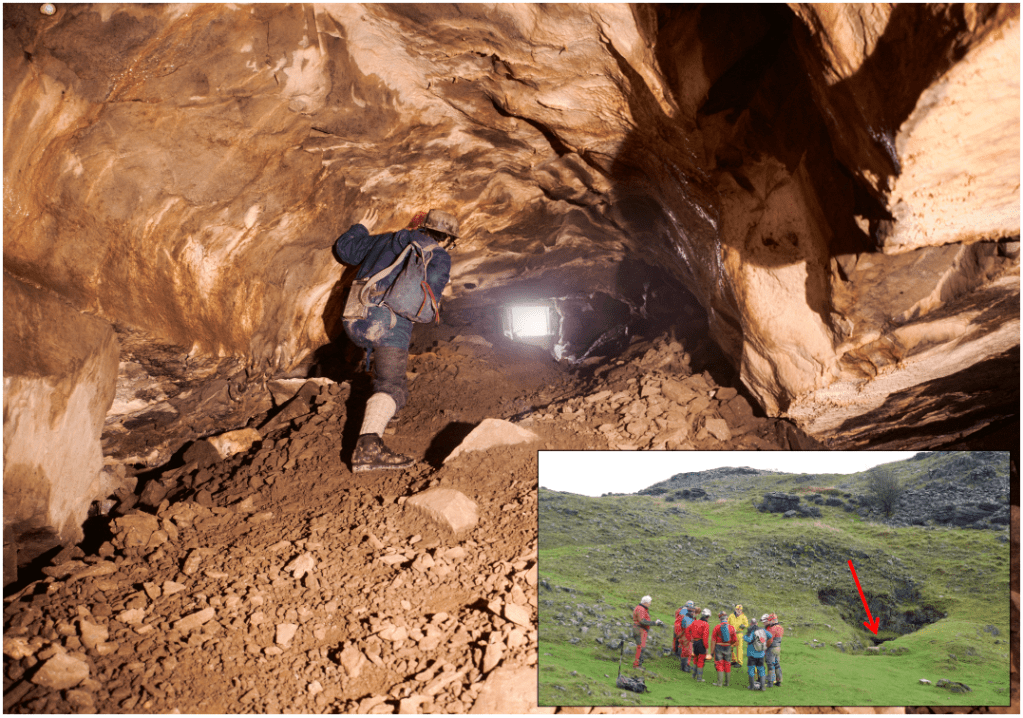

Figure 33. In red is a recent survey of Ogof Ffynnon Ddu (OFD) ‘placed within’ the limestones around the South Wales Caving Club head quarters (SWCC; SN854 158). The main active streamway is primarily fed from a stream sink top-right with the valley-bottom river resurgence mid-left. The main point is that the cave falls 309 m from sink to resurgence and has for millennia been migrating downwards by limestone dissolution with some mechanical erosion, leaving earlier passages stranded and dry nearer the ground surface. However, because of 10s of millions of years of uplift and surface erosion, the present surface intersects cave passages that originally formed beneath a water table. For example, the ‘top entrance’ passage several metres wide and showing phreatic (within-water table) development (Fig. 34) now projects into space above the hillside. Base image: GOOGLE EARTH display of OFD Survey. (KMZ) – copyright South Wales Caving Club.

Figure 34. ‘Top entrance’ of OFD showing it to be originally a large phreatic passage, formed beneath a water table, now truncated at the surface through substantial uplift and erosion. (The passage now has partial fill of talus. Main photo courtesy of Paddy & Sue O’Reilly; inset Helen Nightingale).

It is practically impossible to imagine where the original surface exposure of limestone was when caves initiated here many millions of years ago. The limestones dip southwards and here are locally covered by gritstones. The original contact of water with limestone 10s of millions of years ago was probably much farther north than the present sink and at an elevation now in the sky. The main takeaway is that all of the present OFD system originally formed beneath a water table but the water table now is at the level of the active streamway governed by the resurgence level in the main valley. This demonstrates the substantial uplift with associated river incision recorded in the existing limestone, never mind that previously stripped away from above it (see Freem & Kokelaar pp. 141-150 in Collings-Wells 2025).

Existence of OFD as substantially formed before the Ice Age is evident in the recorded presence of sediments that temporarily filled passages but then were mostly washed out. The substantial amounts of sediments almost certainly were formed by glacial ice action upstream and overhead; they leave their signature erosional imprints widely around the level of the ‘top entrance’ (Fig. 35).

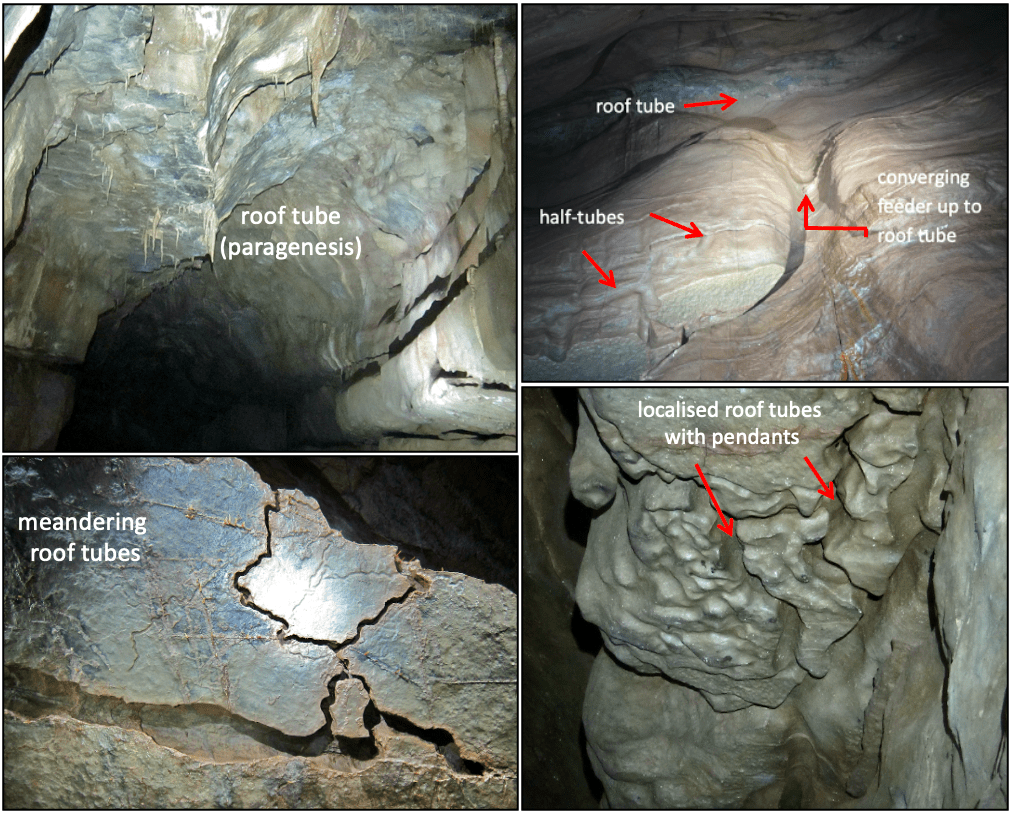

Figure 35. Dry upper-level passages in OFD widely show that previously they were temporarily filled with sediments, almost certainly glacial in origin; vestiges of this infiltrated sediment remain in places cemented to passage walls or incompletely eroded out and forming banks. Where passages are sediment-filled water tends to percolate along contacts with the limestone. Where water flows on top of sediment the limestone dissolution forms a roof tube and the passage enlarges upwards. This is known as paragenesis. Half-tubes and feeders etched in limestone map the main contact watercourses where sediments existed but are no longer in place. These features warrant research in terms of timing, of the initial phreatic development and the subsequent sediment infilling and washing out reflecting glacial cycles. (Precise scales of the images are hard to demonstrate but the fields of view of the two top images are approximately 5-6 m wide and the lower two about 2 m wide).

Figure 36. Diagrammatic illustration of the successive stages of uplift, erosion and flooding of Gower limestones. A. As everywhere across western Britain, all rocks were episodically uplifted for 10s of millions of years, here, including the Carboniferous Limestones, by at least 1 km. The local limestone massif would have eroded normally with valleys and gorges that influenced the level of the contemporary water table. Caves initially formed beneath a water table would successively drain as the water table lowered during uplift and incision, much as is recorded in ODF today (see above). B. At around 3 million years ago marine planation truncated the massif to form the gently sloping platform we see today, along much of our coast at around 60 m OD (Fig. 1). Original valleys and gorges were ‘decapitated’ leaving what we call the ‘headless slades’ today – erosional features with no headwater catchment now. Large valleys that formed before 3 million years ago were enlarged during the ‘Ice Age’, probably both beneath ice and by rivers in interglacial episodes. Similarly, cliffs were eroded back in successive stages and at various levels. All these erosional developments revealed previously developed caves, many becoming relics far removed from the original water courses. Active cave rivers resurged freely as normal. C. Sea-level rise caused sediment choking of active resurgences, forcing waters to emerge from misfitting tight springs above the previous open passages, and burying original outlets beneath estuarine and marine deposits. This local evolution explains the difference with inland, north-crop Carboniferous Limestones… Whereas cavers exploring systems like OFD had a full 300+ metres of sink-to-resurgence limestone to explore, here we were left with only some 75 m thickness as maximum, with old upper parts removed and more youthful lower parts choked and inaccessible! No wonder cave exploration on Gower suddenly practically died in the 1960s when Swansea Valley caves were revealing their vast and extensive secrets…

Geology and ice flow

Current end of draft….

Bögli A (1964) Mischungskorrosion: Ein Beitrag zum Verkarstungsproblem. Erdkunde 18, 83-92.

Bögli A (1980) Karst Hydrology and Physical Speleology, 284pp, Springer-Verlag: Berlin.

British Geological Survey (2002) Worms Head. England and Wales Sheet 246. Solid and Drift Geology. 1:50 000 Provisional Series. (Keyworth, Nottingham: British Geological Survey).

Collings-Wells P (2025) Ogof Ffynnon Ddu – a photographic exploration of the deepest cave in the UK (with 34+ contributors), WhiteSpringBooks and Gomer Press, 170 pp.

Jehu TJ (1904) The glacial deposits of Northern Pembrokeshire. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 41, 53-87.

Kokelaar P 2024 Gower’s inland flooding: Legacy of the last glaciation of Wales. Gower Journal 75, 6-11.

Kokelaar BP, Howells MF, Bevins RE, Roach RA 1984 Volcanic and associated sedimentary and tectonic processes in the Ordovician marginal basin of Wales: a field guide. In Kokelaar BP, Howells MF (eds) Marginal Basin Geology. Spec. Pub. Geol. Soc. London, 16, 291-322.

McCarroll D, Stone JO, Ballantyne CK, Scourse JD, & 3 others (2010) Exposure-age constraints on the extent, timing and rate of retreat of the last Irish Sea ice stream. Quaternary Science Reviews 29, 1844-1852.

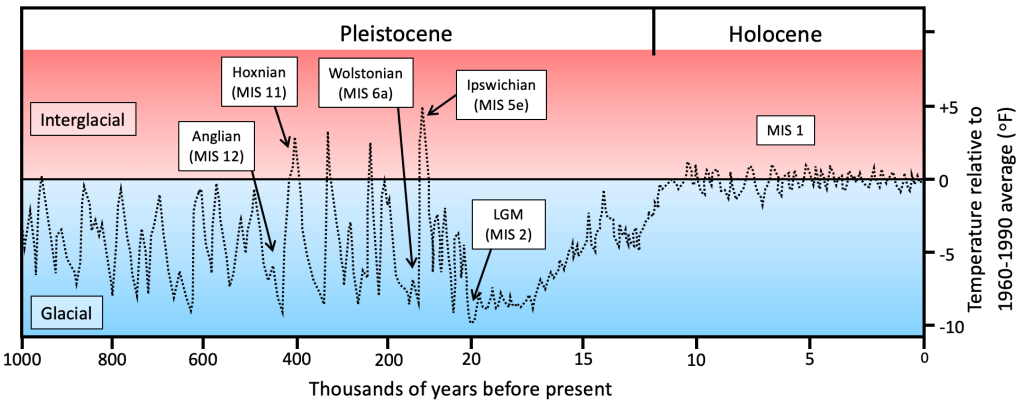

Global temperature fluctuations of the last 1 million years; note the timescale change at 20,000 years. The Pleistocene trace is a hybrid of Antarctic and Greenland data modified to represent global conditions (Lisiecki and Raymo 2005; Jousel et al. 2007). Global temperature estimates over the ~12,000 years of the Holocene are from Marcott et al. (2013). LGM is Last Glacial Maximum; MIS is Marine Isotope Stage.

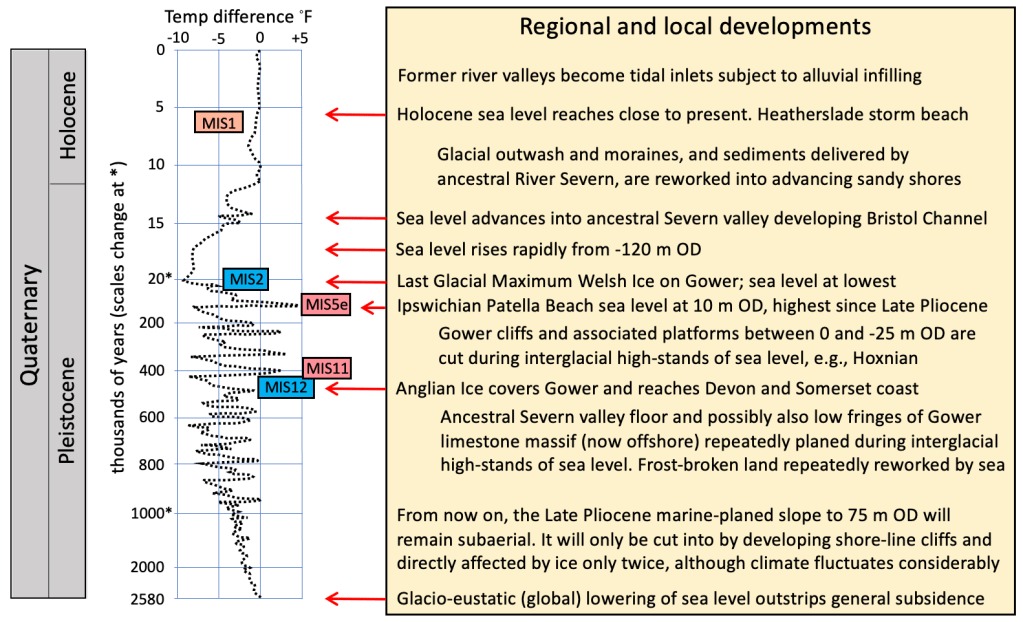

Quaternary global and regional developments related to Gower landscape evolution. The temperature variation curve is redrawn from Lisiecki and Raymo (2005), Hansen et al. (2013) and Jouzel et al. (2017).

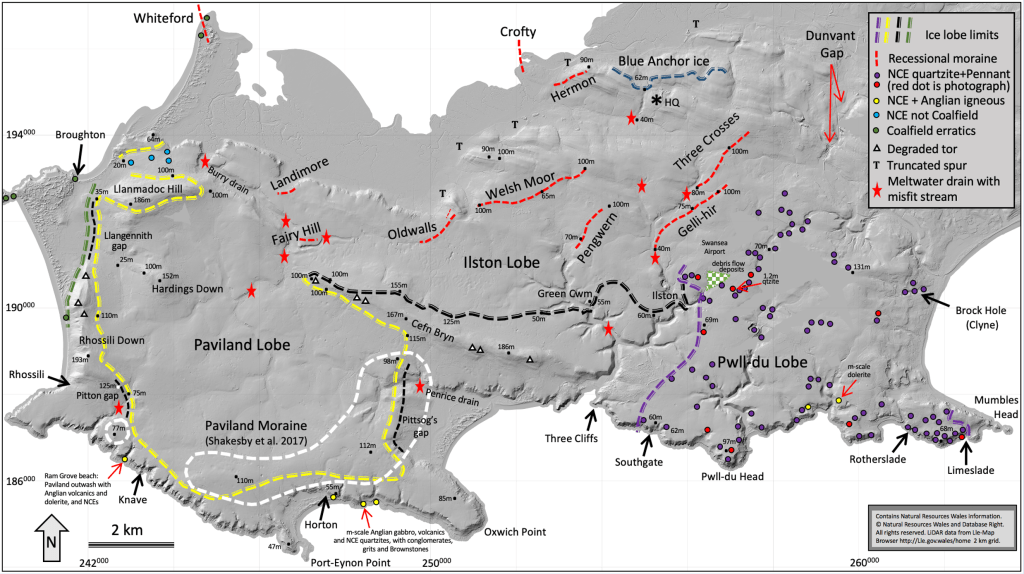

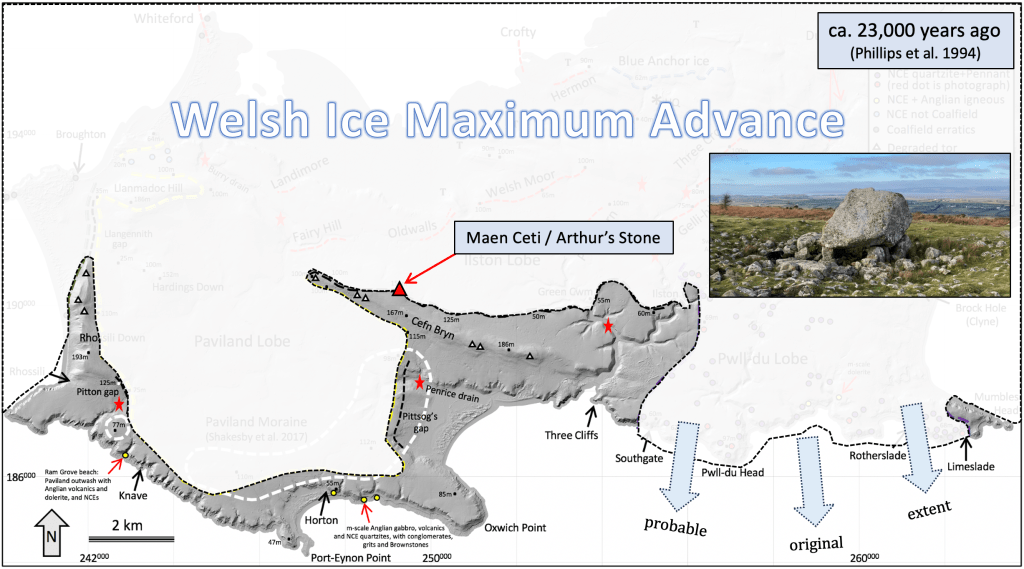

Updated map of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) limits on Gower. (The shaded-relief LiDAR image was processed using base data © Natural Resources Wales). The Paviland Lobe margin is continuous with the Ilston Lobe margin, which traces along the north flank of Cefn Bryn, across Green Cwm to Ilston Cwm. These ice maximum limits probably were broadly contemporaneous.

The Pwll-du Lobe cuts across and is distinctly different from the eastern reach of the Ilston Lobe, being marked by substantially larger quartzitic north-crop erratics (NCEs) with abundant relatively angular Pennant blocks and limestone (only towards the southwest), in addition to ‘normal’ north-crop LORS Brownstones and UORS quartz-pebble conglomerate. The purple and red dots mark the main exposures of the large erratics that distinguish the Pwll-du Lobe.

The most obvious Anglian erratics within the Pwll-du Lobe are dolerite, but Gower-type UORS quartz-pebble conglomerate boulders are also Anglian. Coastal exposures commonly show a mixture of north-crop erratics with a few Anglian erratics and some Triassic sandstone fragments. These coastal deposits show evidence of aqueous and debris-flow transport, with normal steep-slope solifluction, and they represent reworking of the post-LGM landscape during ice recession.

Dunvant Gap is the pronounced cutting through the Pennant sandstone ridges of northeast Gower. Unlike other breaks in the ridge topography, this most prominent breach is not obviously controlled by any faults (British Geological Survey 2011).

Interpretation of the Last Glacial Maximum ice limits based on the map above. Arthur’s Stone marks the high limit on Cefn Bryn; next time you visit there, imagine that to the north across the modern Loughor Estuary and over the hills towards the Gwendraeth valleys you would have seen only the Welsh ice sheet.