This section started life simply reporting my ‘visit out of interest’. I had collected Anglian erratics on Gower that clearly had been transported by glacier ice on its way ‘towards Stonehenge’ from Pembrokeshire (see previous section)… So I thought it would be interesting to see what is there. The report, however, developed into something of an essay, from trying to find out and write down what really is known about the Stonehenge ‘bluestones’. I found a jumble of confusing claims, counterclaims and manifest nonsense, with a good measure of misleading media hype thrown in. Heaven only knows what truly interested people in general think about how the bluestones got to Stonehenge; most people I talk to innocently subscribe to “remarkable human transport”, because that is what the BBC and several newspapers have sold, repeatedly. To save the reader from any suspense here, perhaps, cutting away some nonsense and applying Occam’s Razor (i.e., simplest tends to be best), I come out in favour of “mostly transport by ice”. (I apologise for the unavoidable use of some technical terms, which I try to minimise or explain; I have favoured illustrations instead of text where possible. Reader please be aware that this is work in progress – substantially incomplete and liable to change! I am open to constructive criticism and discussion of my ideas – see the section on feedback – and would hope to be properly acknowledged if they are recycled.)

A visit to see the Stonehenge ‘bluestones’

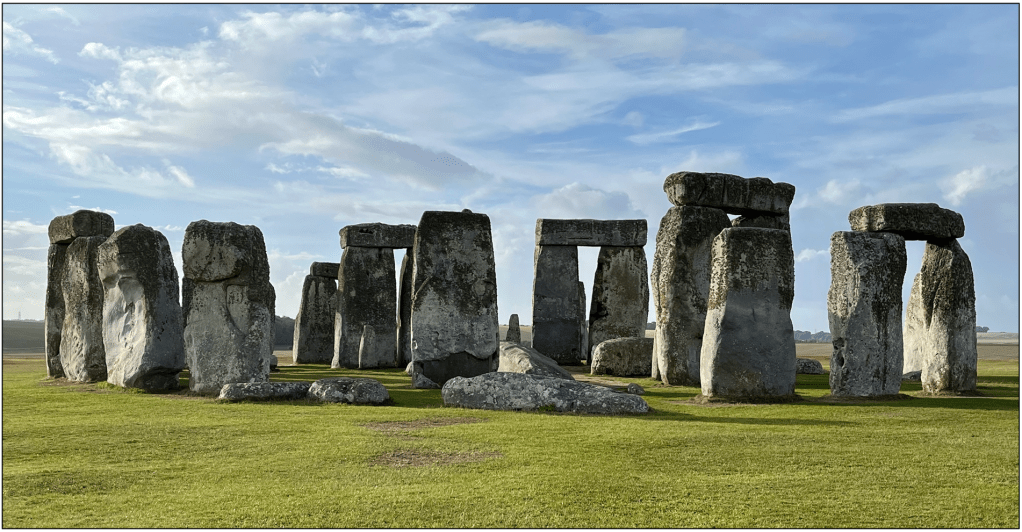

September 1st 2025: with wonderful early morning light and a brief respite from persistent thick cloud and thundery showers, an ‘English Heritage Inner Circle Experience’ afforded a close look at Stonehenge and in particular its enigmatic bluestones. (‘Bluestones’ is a bucket term for the rocks there that aren’t sarsen sandstones.) Main impressions: it is worth the cost to be free to roam amongst the stones before the hordes arrive ‘outside’, most of the the bluestones are familiar friends from Pembrokeshire, and the common ‘spotted’ dolerite is not a rock type found amongst Gower erratics.

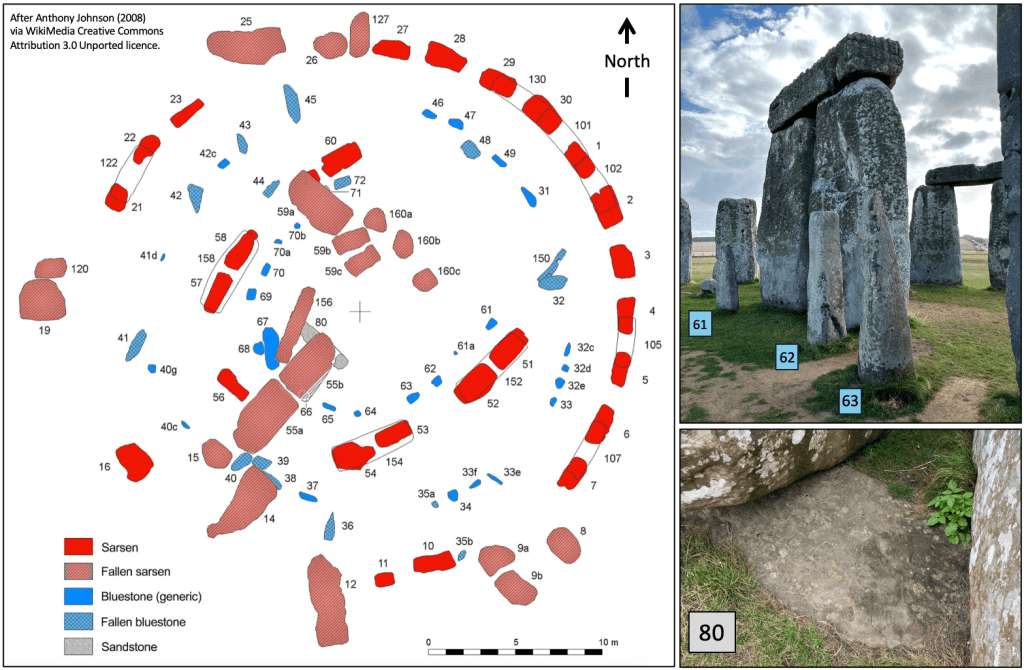

Figure 1. The site is dominated by the huge ‘sarsens’ of tough sandstone while the bluestones form a circle and a horse-shoe pattern within the megalith periphery. Anthony Johnson’s map gives the conventional stone numbering, locating, e.g., 80 as the only exposed non-sarsen sandstone. This one is known as the Altar Stone and is of Scottish origin, although, like the bluestones, its ‘path’ to Stonehenge is debatable (see below).

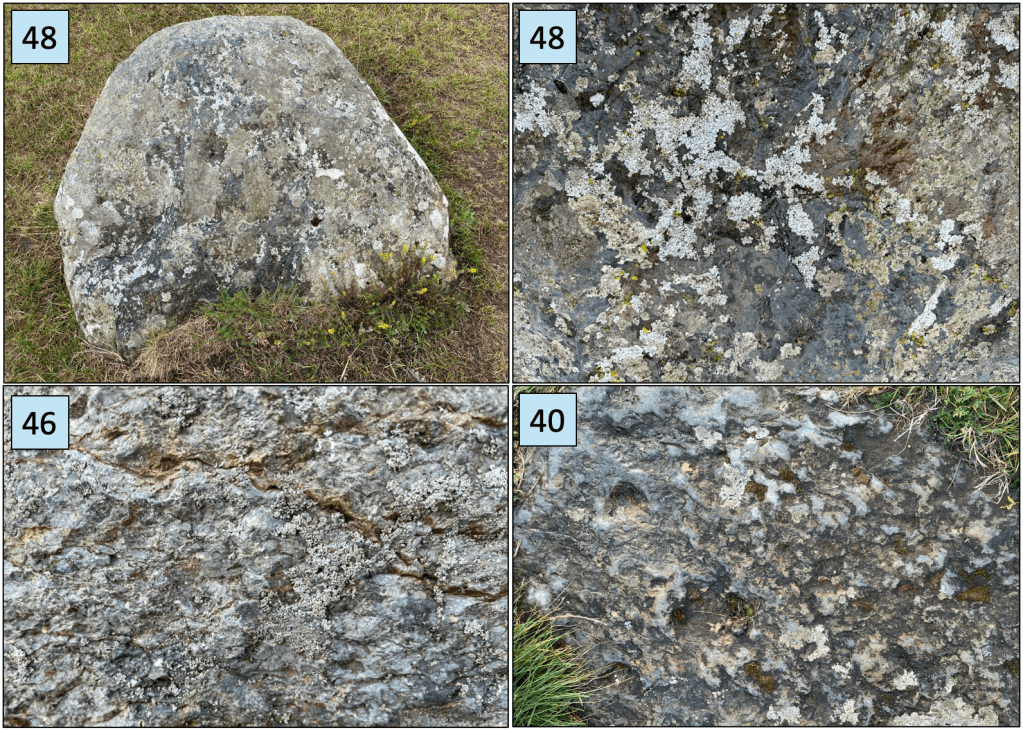

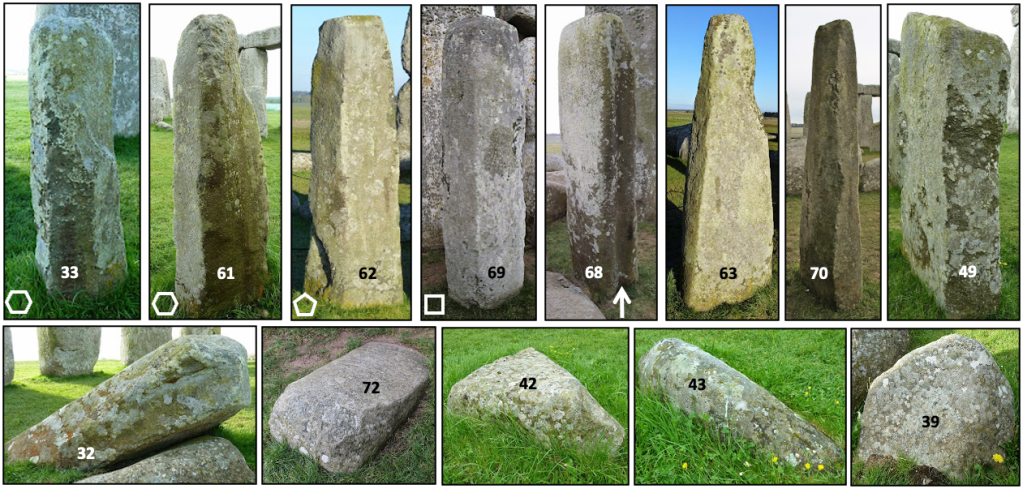

Stonehenge bluestones (Figs 2, 3 and 4) are mostly of spotted and unspotted dolerites, averaging more than 1 tonne with several perhaps up to about 3.5 tonnes. These occur with a few significantly smaller stones, of rhyolite, foliated rhyolitic tuff (silicic ignimbrite), and volcanic breccia. All these stones derive from rock outcrops in Pembrokeshire (e.g., Bevins and Ixer 2018). The broken slab of pale green sandstone known as the Altar Stone weighs about 6 tonnes. Rock fragments matching the monumental stones are abundant in the vicinity of Stonehenge and those nearby have been interpreted to indicate manual ‘dressing’ (shaping) at the construction site. Although there are no ‘dressed’ rhyolite stones, some analysed fragments match and are interpreted to derive ultimately from a rhyolitic tuff outcrop at Craig Rhosyfelin (SN1167 3615), also in Pembrokeshire. The so-called Newall Boulder excavated at Stonehenge and the buried stump of Stone 32d share this apparent origin (Bevins et al. 2023). Sandstone fragments also occur, similar to buried stones (40g and 42c), and on fossil evidence these originate elsewhere in north Pembrokeshire (Ixer et al. 2017, 2020; Bevins et al. 2020). Evidence of shaping of the dolerites, which are exceptionally tough rocks, is scarce, although small fragments of both spotted and non-spotted varieties have been found (Bevins et al. 2023). Sockets in dolerite lintel Stone 150 were hand made, while a groove in Stone 68 seems enigmatic, not clearly shaped by hand. Quite a few of the Stonehenge dolerites closely resemble the polyhedral (flat-faced and sharp-edged) joint columns and blocks that occur naturally amidst and fallen around their source outcrops in the eastern Preseli hills, but many of the bluestones are to an extent rounded, with some unquestionably of abraded round shapes like classic erratics (Fig. 4). As noted by many authors (e.g., Thorpe et al. 1991), the bluestone assemblage in its entirety is a mix that one would expect to have been deposited at the limit of an ice sheet, where large rocks had been transported on top (supra-glacially) with smaller more rounded stones having travelled within or at the base of it.

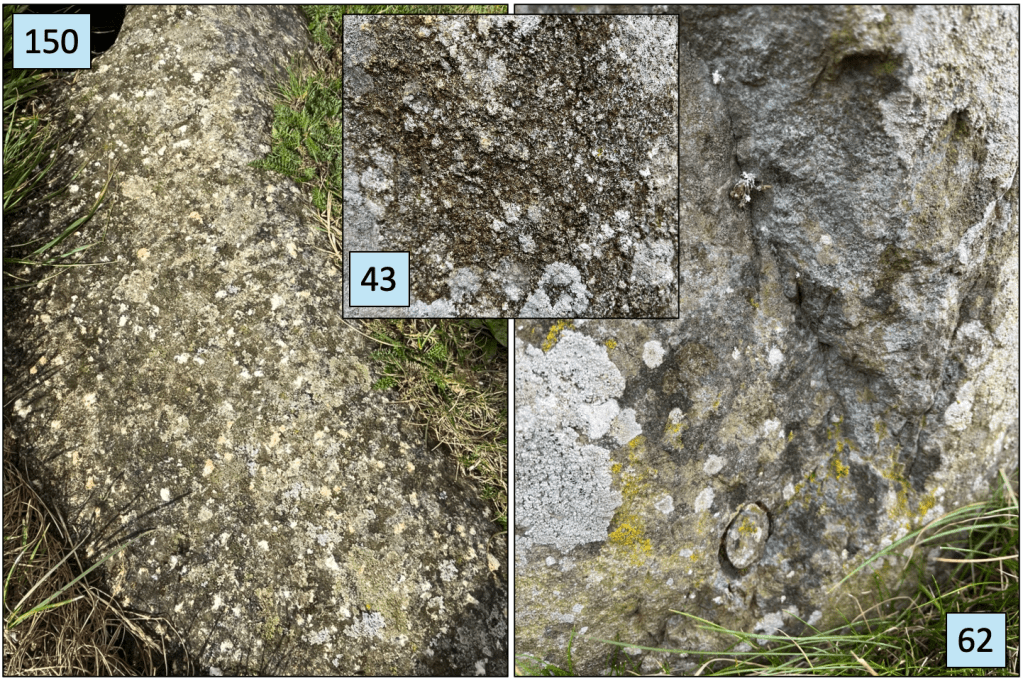

Figure 2. Stones 150 and 43 are of the common ‘spotted’ dolerite, while 62 is one of the only three non-spotted dolerites (the others are fallen Stones 44 and 45), with the cut ring showing where a core was taken for analysis. Above the core site the dolerite is freshly broken revealing some clean rock; elsewhere the surfaces are widely obscured by centuries of weathering and by diverse lichens. Stone 62 has been found to be compositionally similar to the eastern Preseli natural dolerite outcrop of Garn Ddu Fach (SN151 332). It is geochemically unlike a group of non-spotted stones 7 km west of there that was inferred to be part of an early monumental site and incorrectly interpreted to be its source for transport to Stonehenge (see below).

Figure 3. Broadly speaking*, Pembrokeshire igneous rocks are compositionally of two main types, dominated by the relatively silica-poor basalts, dolerites (as found here) and gabbros, with less abundant relatively silica-rich rhyolites and dacites. Stone 48 is a well-rounded erratic of rhyolite, with 46 being the only other exposed rhyolite (Stone 32d, a broken stump, is buried) but in this case with an indistinct foliation (left to right here). Stone 38 (not shown) is a poorly exposed, rounded, silicic volcanic erratic, and Stone 40 is another silicic rock, apparently a volcanic breccia and reported as dacite. *(There are intermediate compositions, but volumetrically they are far less abundant).

Figure 4. Twenty-four of the known forty-three bluestones at Stonehenge. These are sufficiently well exposed to show the range of original shapes, from polyhedral cooling-contraction-jointed columns of dolerite (top left) through to well-rounded erratics (bottom right), including the two rhyolites. Stone 150, perhaps originally a lintel bridging across upright stones, shows a hollow made to receive a locating boss (red arrow). A groove in the side of Stone 68 (white arrow) is of unknown origin. Photos cropped from Simon Banton’s ‘The Stones of Stonehenge’ http://www.stonesofstonehenge.org.uk licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

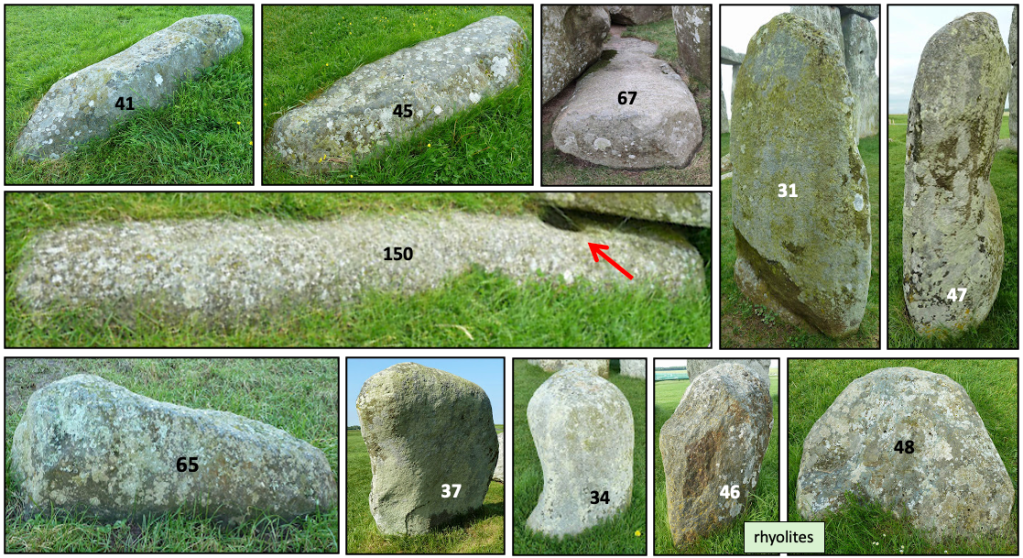

In the following sections I outline some of the propositions regarding the transport histories of the Stonehenge bluestones. There is robust geochemical evidence that the bluestones, except for the Altar Stone, were derived from rock outcrops in Pembrokeshire. Similarly, there is no doubt that the Pembrokeshire source region of igneous rocks was over-ridden by glacial ice, much of it clearly part of the Irish Sea Ice Stream that also advanced over Gower and parts of old Glamorganshire some 450,000 years ago. I have no certain knowledge of how the bluestones arrived at Stonehenge, whether by ice, by human power, or perhaps by some hybrid of agents, but I do offer a simple model as a possible explanation. I do know, however, that the ‘debate’ has involved somewhat alarming instances of serious subjectivity and media hype unlikely to promote the lay person’s trust in ‘expert opinions and methods’, probably to the contrary.

Figure 5. Top. Map showing the penetration of the Irish Sea Ice Stream into what is now the Bristol Channel and, in yellow, the probable Anglian (450,000 years BP) ice-transport path based on unequivocal occurrences of Pembrokeshire igneous erratics on Gower and farther east as far as Flat Holm (see previous section). The ‘contentious reach’, which is between the proven ice penetration and Stonehenge, is an area where bluestone fragments are widely dispersed and interpreted by some as glacial debris and by others as human-scattered detritus. Bottom. Overland and sea routes proposed as alternative ways that humans transported bluestones from the Preseli sources to Stonehenge (modified from English Heritage Stonehenge by Julian Richards, p. 8, and the English Heritage Stonehenge website). An additional suggested sea route that circumnavigates the entire southwest peninsula, around Lands End, seems sensibly ignored. The blue arrow shows the likely path of bluestones transported high within the ice or on top of the ice (supra-glacially) from source outcrops forming one or more nunataks near the summits of the Preseli hills (see below).

Glacial progress

There is little point in reviewing all of the claims and counterclaims made in the previous century regarding the transport of ‘bluestones’ to Stonehenge (initially Judd in 1902 by ice, then Thomas in 1923 by humans). Scourse (1997) provides a usefully comprehensive review before an analytical discussion of the glacial transport hypotheses. The latter analysis comes out not to favour ice, seemingly because there is no clear evidence of glacial transport all the way to the vicinity of Stonehenge. He discusses the paucity of material evidence on Salisbury Plain, such as in unequivocal erratics, till or substrate scour marks, and a lack of evidence for ice having surmounted and somehow modified the Mendip Hills or the Wiltshire Downs escarpment and Chalk strata ‘on the way’. But these perceived problems all go away if glacier ice, at its relatively thin and wasting maximum reach, really did deliver large robust rocks near enough to warrant their collection and removal to the ceremonial site… Here, now, this last remark may look like a special plead, but, when all of the claims for human transport are stripped away for being without any foundation, ice is the only obvious agent, even if the last reach of it is not obviously or unequivocally recorded. Largely because of the media hype, which persistently favours the “extraordinary human endeavour”, ice transport currently gets practically no mention (e.g., BBC’s Countryfile on Stonehenge of 14th December 2025), but that is misleading. Ice transport warrants the light of reasonable consideration.

What follows here in no way settles the transport dispute. For the foreseeable future both sides will be able to claim a “dearth of direct evidence”, but what follows offers an extremely simple explanation seemingly overlooked before. It is glaciologically fairly sound and makes it easy to shelve human transport, with all its difficult-to-imagine and impossible-to-disprove elements, and its once-claimed ‘evidences’ now debunked (e.g., Parker Pearson et al. 2010; John et al. 2015; Bevins et al. 2022). Occam’s Razor springs to mind. Later we will recall some of the media’s misdirected presentations of the human transport view as if it was well supported by archaeological or scientific facts. This has been a bizarre distraction at least, if not damaging.

Little bits of background. It is important to consider that if ice delivery to within reach of Stonehenge occurred 450,000 years ago then rocks stranded there and exposed to the elements for so long would be thoroughly weathered, with the less robust types probably rendered to small fragments (‘chippings’), small weathered stones or soil in the interim, e.g., the 77 pieces of ‘granodiorite’ totalling 22 kg excavated at West Kennet, Avebury (Ixer et al. 2025). That long interval here involved several extremely cold (glacial-periglacial) and relatively warm (interglacial) episodes. Periglacial freeze-thaw shattering (thermoclastic fragmentation) typically produces angular stone chips and part of the Stonehenge transport controversy concerns whether or not the widely extensive occurrence of many thousands of bluestone and other fragments on Salisbury Plain (e.g., Ixer and Bevins 2010) registers glacial delivery with subsequent periglacial material degradation. There has been a strong tendency to interpret all fragments of monolith stone types as reflecting ‘dressing’ by human hands and thus to refer to them as ‘debitage’. This might be justified in the vicinity of the monuments, but the interpretation potentially involves circular reasoning. As carefully detailed by Thorpe et al. (Table 2, 1991), the occurrences widely scattered, e.g., 30 km north around Avebury and 3 km south near Lake, and the combination of pieces of known erratic types in Barrow Amesbury 39 (a burial site), which pre-dates erection of the large stones of Stonehenge, suggest a natural distribution and render associated claims of human scattering special pleading. Also, amongst the thousands of fragments there are non-bluestone rock types, such as basaltic tuff (e.g., Ixer and Bevins 2010), which occurs in Pembrokeshire but is not known at the megalith site and would not have made robust monumental stones. Further, from my own experience of mapping glacial deposits on Gower, one simply should not dismiss field clearance of stones that superficially looks like original absence. Centuries of land clearance on Gower has led to piles of Devensian erratics being formed into field-boundary banks (one of which I initially mistook for a moraine), and significant clearance over millennia is to be expected on the Wiltshire Downs.

Relatively recent excavations around Stonehenge (Allen et al. 2016; Leivers 2021) have revealed a very extensive tract of monumental ground – “Sacred landscape” – and, for our particular interest, also an early bluestone henge site from which our stones apparently were removed to Stonehenge. The excavations found bluestone chips as well as areas of “periglacial frost-heave (cryoturbation) features primarily created by in situ freeze-thaw alteration of the chalk…”. These frost features are well described and known to occur widely on the gentle chalk slopes of Wiltshire. So we know of typical periglacial conditions here and that the bluestones seemingly were moved to be reused at the present site as if they were not readily available for supply.

If the stones were glacially delivered, it would explain why experts on Stonehenge archaeology have commented that the site was never fully completed although repeatedly restructured (Late Neolithic ca. 2950 BC to Early Bronze Age ca. 2,100 BC; Parker Pearson 2023). Based on the irregular gaps (Fig. 1) and the use of rather unremarkable and mixed types of small and rounded stones, it has been inferred that the source of substantial dolerite bluestone megaliths became “used up”, so that a full pattern of pillars was never completed. There are 43 stones known today; filling the gaps hypothetically yields 80.

One might guess that any actual quarry selection and transport by humans would have produced something more uniform or regular, and not as it seems to be, i.e., exactly what one would expect from a natural distribution, not all of robust dolerite, and of varying shapes from columns to rounded irregular weathered forms (Fig. 4). However, we are reminded that we should not presume to know the Neolithic (2,500 BC) mind set… But, the huge effort, the very real physical risks, and the considerable time that would be taken in transporting so many unremarkable heavy rocks so far inexorably seems contrary to our modern common sense. Repeated re-use of the seemingly insufficient bluestones over many centuries also does not suggest their derivation from known accessible quarries or pre-existing monuments. Further, the argument that bluestone erratic material should exist in river gravels if it was ever delivered by ice, is spurious, because there is no need to claim an original thick or widely extensive till cover reworked and eroded off Salisbury Plain. All that is needed is the collection and removal of a few prominent weathering-resistant stones across periglacial terrain from their unrecognised area of glacial deposition, with weathered remnants remaining unlocated and/or removed in millennia of ground clearance. The recent paper on residual zircons and apatite in 4 samples of river sediments from around Salisbury Plain (Clarke and Kirkland 2026) finds robust age spectra consistent with the Laurentian basement of northern Britain, just like the Altar Stone (see below). However, it argues that the material was derived from mass wasting of originally overlying strata (Thanet Formation 59.2-56 Ma old), and, that the paucity of more southerly-derived material (despite one of Ordovician age of ~464+/-16 Ma consistent with bluestone provenance) indicates that ice transport was not involved. The arguments are tortuous, subjective and closed to ice, but in any case the mineral samples do not derive from farther west where ice could have dumped bluestones to be collected. It was interesting to me to find that igneous erratics from the potential southerly sources of the English Lake District and Snowdonia have not been found on Gower, while Scottish rocks do occur (see previous section and below).

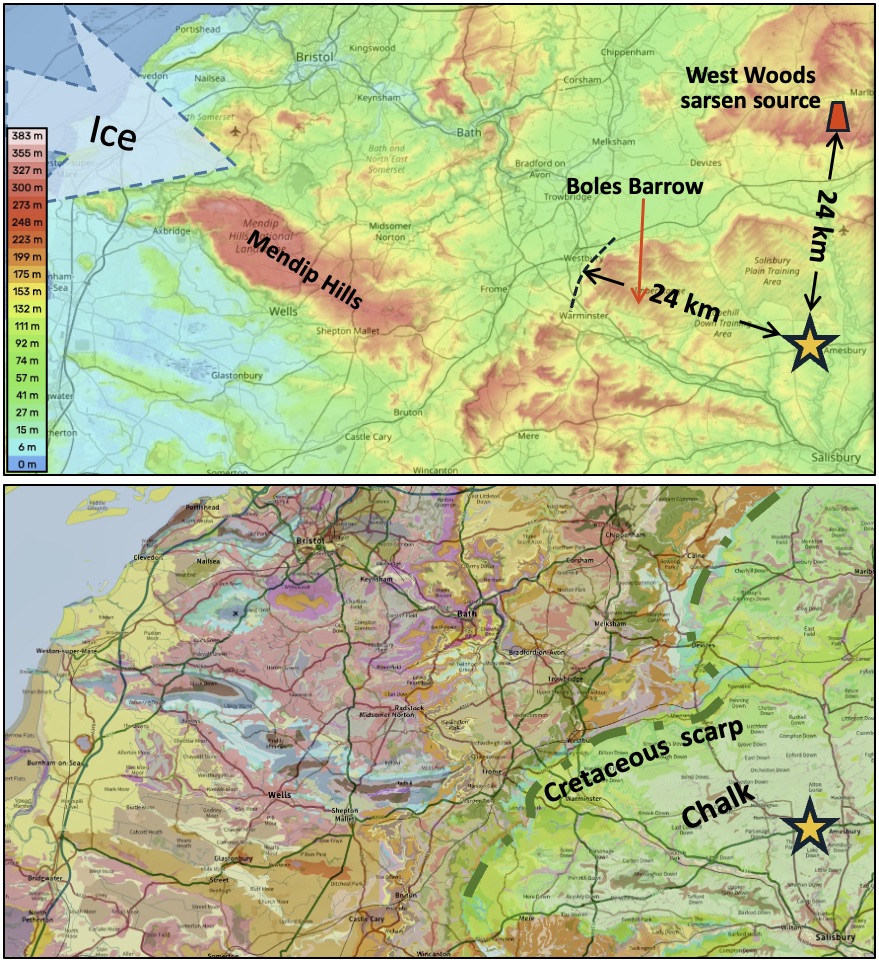

Conversely, in the human-transport view, Stonehenge would be the only known ritual site where numerous (at least 43) pieces of non-local and not especially remarkable material, up to 3.5 tonnes in weight, were carried several hundreds of kilometres (overland some 300 km / 186 mi and by water 435 km / 270 mi). There is no known field record of this anywhere. We do know, however, that prominent, weather-resisting stones lying around within a largish area – perhaps 10s of kilometres away – definitely were commonly collected, brought together and carefully erected. Some of the Stonehenge sarsen stones, a few over 30 tonnes, are thought to have been collected from about 24 km away (Field et al. 2015; Harding et al. 2024; Daw 2025). In the Preseli area spotted dolerite stones were only used where they occurred locally, near to where they are found today, and there exists no evidence of them being especially revered. Motivation for the “stupendous feat” in human transport has always been a problematic weakness in the case, earlier attributing fantastic reasons like magical powers or sonic properties to the stones, or later mistakenly claiming reverence for them in sites of previous circles that then acted as sources for removal and transport (e.g., Parker Pearson et al. 2021). Fantastic claims, including inference of active quarrying to produce the stones at rock outcrops that are actually typical of natural jointing, weathering and collapse, are now, with sensible geology and geomorphology, and with robust geochemical evidence, thoroughly debunked. So, no quarries and no uprooting of former monuments (Bevins et al. 2022; John et al. 2015; John 2025).

It doesn’t really matter. Perhaps most notorious in the ‘debate’, and illustrating how confusing it can be if one is trying to understand what actually is known, is the recorded finding of a spotted dolerite boulder (80 cm diameter, ~340 kg) built into the structure of Boles Barrow (a burial mound) 19 km west-northwest of Stonehenge. It was found by William Cunnington who excavated the barrow in 1801 and apparently it occurred together with other boulders of sandstone akin to the Stonehenge sarcens. Contemporary letters note that sarcen boulders are common in the vicinity and also, from a sample flake sent to HH Thomas of the Geological Survey (he of human-transport conviction), that “There is no doubt at all that the specimen … is of the spotted Prescelly type and identical with the spotted Blue stones of Stonehenge.” (Cunnington 1924). Critically, the barrow’s construction predates Stonehenge by some 1000 years so that this boulder seems sensibly interpreted as an erratic and thus evidence of ice transport as far as there. However, the range of convoluted and contradictory claims made through time, not helped by the boulder being temporarily lost and including the suggestion that it was transported to Stonehenge and then stolen for a garden ornament (subsequently refuted), is astonishing and mind-numbing (for a fair reflection, search Boles Boulder in Brian John’s blog https://brian-mountainman.blogspot.com/ and see Burl (1999) and the Cunnington (1924) paper at https://archive.org/details/wiltshirearchaeo421922192/page/n483/mode/2up). Similarly, there has been considerable ‘debate’ as to whether the so-called Newall boulder, of rhyolite (22x15x10 cm) excavated at Stonehenge in 1924 and known to originate on the north flank of the Preseli range (Craig Rhosyfelin), is a weathered erratic or a weathered fragment from a human-transported stone (Bevins et al. 2023, 2025; John 2024). It was in a collection of small rock fragments that included spotted dolerite, dolerite, andesite, rhyolite and sandstone, and even 100 years ago these were of disputed origin – thought by Newall to be erratics. The abundant fragmental rhyolitic debris at and around Stonehenge that also apparently is derived from Craig Rhosyfelin and taken to be waste (debitage) from stone reworking (Bevins et al. 2012), also suffers from unknowable transport to the site. However, these contentious and ambiguous cases are not materially relevant to any human- versus ice-transport judgement. Similarly irrelevant is the inferred human transport of the Altar Stone, a (broken) sandstone slab interpreted to have come from northeast Scotland. As explained below, this stone is likely to have come from western Scotland, and, like the Ailsa Craig erratics, delivered via the Irish Sea Ice Stream. The ‘evidence’ is always ambiguous, so perhaps a really simple model explanation could be favoured…

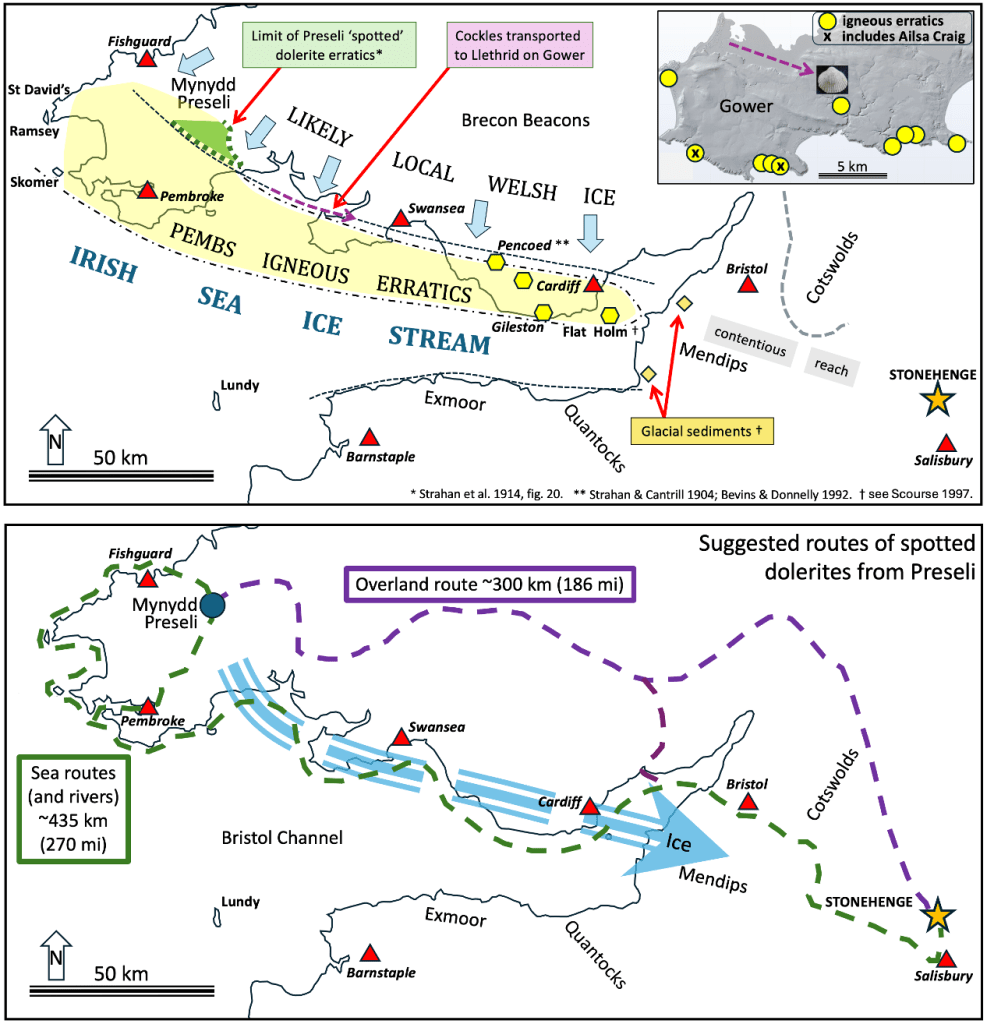

The far-fetched Altar Stone

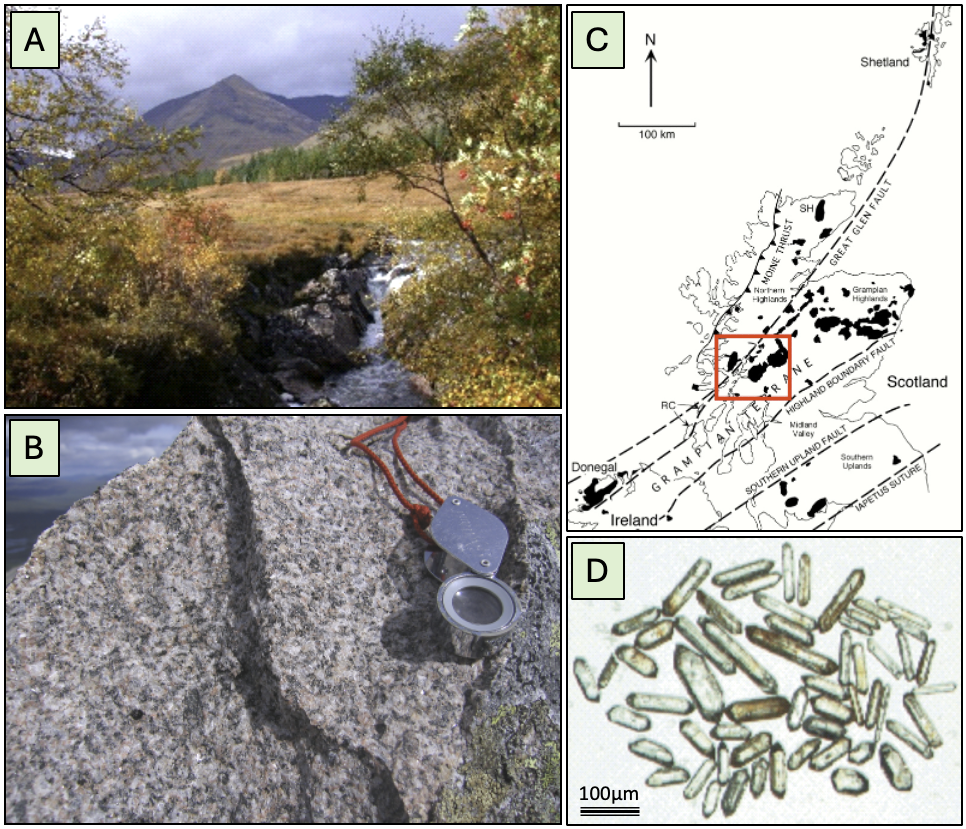

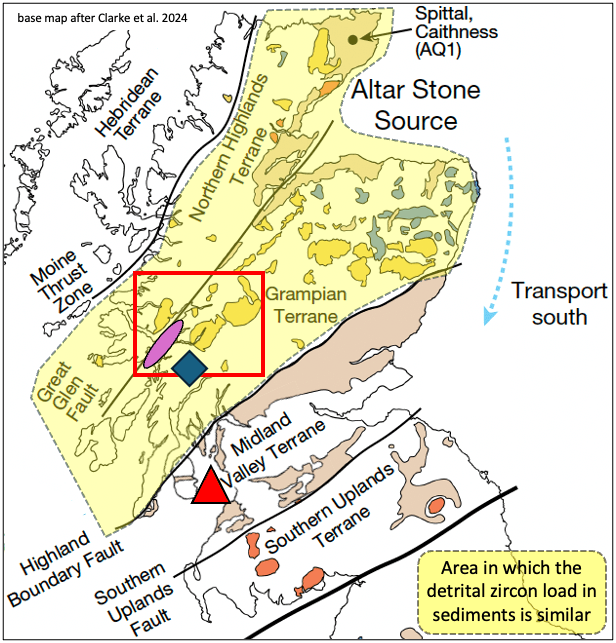

This broken 6 tonne sandstone slab has been considered as one of the bluestones since it was first thought to come from Pembrokeshire along with the others. Cutting through a great deal of painstaking work that was done to locate a source, finally, in 2024, its Scottish origin was reported (Clarke et al. 2024; but see also Bevins et al. 2024). There was considerable media attention, primarily centred then on the colossal apparent transport distance from north-easternmost Scotland to Stonehenge. Human transport by sea was favoured rather than such a great distance over land. The Scottish origin is not disputed here, as it was reasonably founded on the close similarity of age spectra found in zircons of the Altar Stone and in Scottish sandstones that occur on both sides of the Great Glen Fault (see below). However, the colossal distance of some 750 km for human transport, far greater than ever contemplated previously, is fairly simply dismissed as improbable in the light of overlooked geology. The figures and their captions below hopefully tell the story.

Figure 6. These are illustrations from my studies in the Grampian Highlands of Scotland together with PhD student Joanne Neilson (Neilson 2008; Neilson et al. 2009). A shows the peak of Clach Leathad (1099 m OD), which is composed of a beautiful monzogranite (B). Our work was to determine the history of volcanoes and the intrusions of granite (s.l.) into them, within the Grampian Terrane of Scotland. The study area is within the red box in C. Our rock samples yielded zircon crystals (D) from which ages of intrusion were determined by Uranium-Lead (U-Pb) dating. The zircon crystals, which are extraordinarily robust and persistent through geological time, were found commonly to contain ancient cores within them that had been picked up (inherited) from the deep crustal source where the molten material originated (see also Oliver et al. 2008). These inherited crystal cores confound the analyses and have to be excluded if possible, as they preserve their original chemistry and older ages. (My further attempts to date lavas here failed because of this inheritance.) However, we know that rapid crustal uplift and erosion of the volcanoes and intrusions here caused these zircons to become free detrital grains in the associated sediments. These are just the same sediments that are supposed to form the Altar Stone, but here they occur in the southwest Grampian Highlands… We know, because they involved the same deep crust of Scotland, that ‘our zircons’ contain the same ‘fingerprints’ (age spectra involving inherited cores) as those that Clarke et al. (Figure 4, 2024) used to invoke the northeastern Scottish source for the Altar Stone. While those authors made comparisons with other crustal terranes of Britain, they did not consider sediments with similar age spectra that are widely exposed in the same terrane in southwestern Scotland.

Figure 7. Top. This shows the area (yellow overlay) in which sediments derived from erosion of the mapped Highland igneous rocks can be expected to have formed sediments containing zircons bearing the same compositional fingerprint. It includes the Orcadian Basin sediments in the far northeast, which Clarke et al. (2024) claimed as the “Altar Stone Source”, but it also shows the area of our detailed study to the southwest, in the red box, within which the purple ellipse locates sedimentary rocks known to be similarly derived and a fair possibility for a southwestern source. The red triangle marks Ailsa Craig and the blue diamond the general vicinity from which the Dalradian metamorphic rock (below) is derived. Bottom. The stone on the left closely resembles the poly-deformed and metamorphosed Dalradian rocks of the Grampian Terrane. It shows an early foliation (E) overprinted by a later pronounced fabric (L). It is characteristic of the so-called Dalradian Supergroup of rocks and, containing small garnets, is closely akin to central Grampian metamorphic basement referred to as the Argyll Group. This rock type is exposed southeast of the purple ellipse (top image), part of the way towards Ailsa Craig. The boulder on the right most probably is of Lewisian granitic gneiss ultimately derived from even farther north, somewhere in the Hebridean Terrane of northwest Scotland. Both of these rocks and other gneisses were recently collected from Horton beach (SS476 855), on south Gower.

Finally on this topic, it should be clear now where this is leading. Sandstones with the zircons characteristic of deep Grampian crust occur in southwest Scotland. Anglian ice known to form the Irish Sea Ice Stream has brought Ailsa Craig and seemingly also Lewisian and Grampian rocks to Gower and so it would seem far simpler to invoke glacial transport of the Altar Stone from Scotland to South Wales, and then on … ‘towards Stonehenge’. Occam’s Razor is still not too dull!

A revised glacial transport model

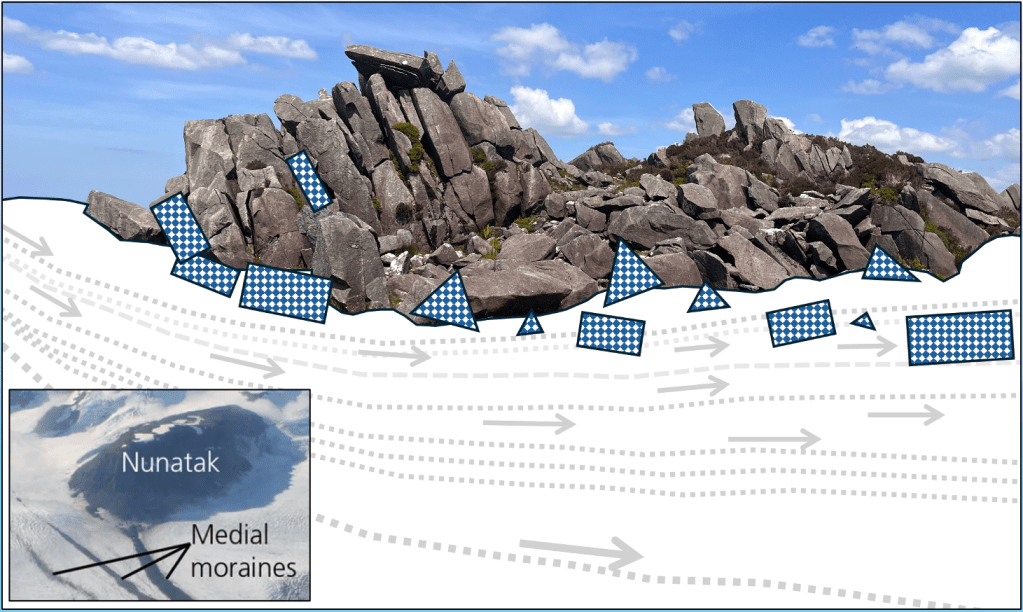

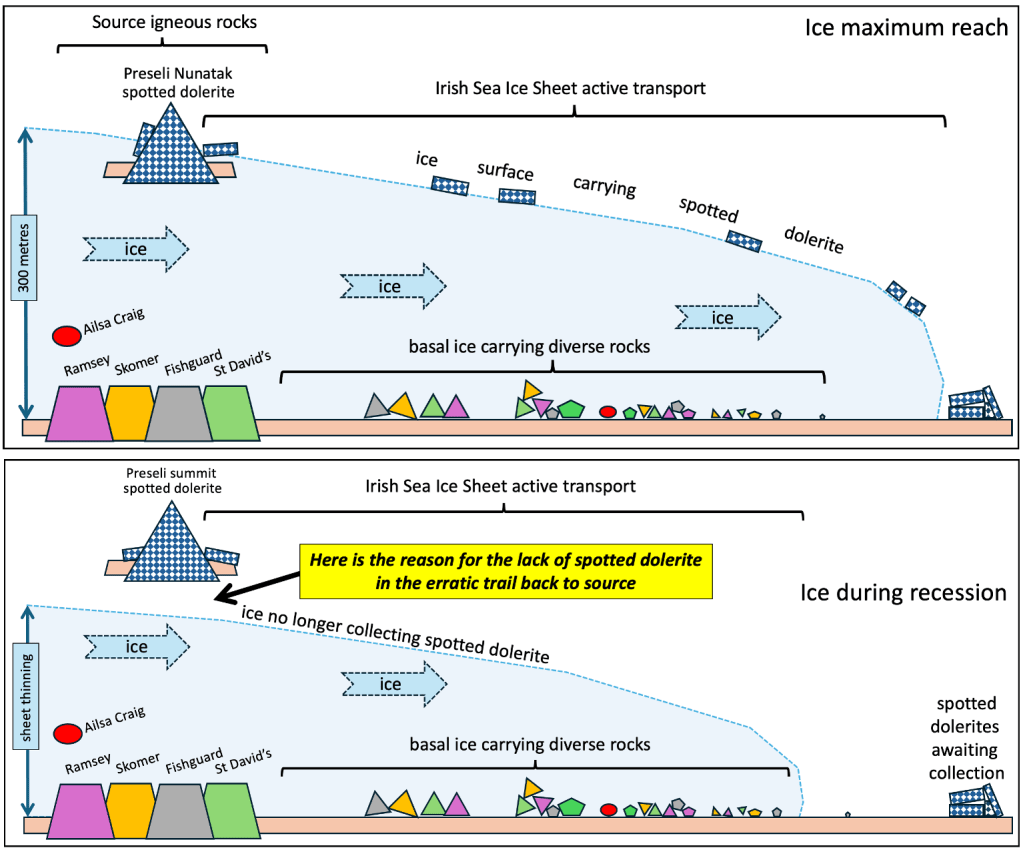

Scourse (1997) discusses at some length the glacial transport favoured and explained by Thorpe et al. (1991). They had advocated transport as free boulders on top of the ice (supra-glacially) from the Preseli summits, having been collected there from nunatak(s) of the spotted and non-spotted dolerites, and with any fines lost through meltwater drainage. That notion was deemed theoretically reasonable by Scourse but seemingly fell at the hurdle of ‘no clear evidence of transport all the way to the vicinity of Stonehenge.’ Thorpe et al. also noted this apparent problem.

But, supra-glacial transport from Preseli nunataks only when the Irish Sea Ice was at its maximum development and thick enough to reach up there, would explain why the spotted dolerite, specific to the high flanks of the Preseli summits, is absent in the otherwise well-populated trail of other Pembrokeshire erratics across Gower and south Glamorgan to Flat Holm. We know ice-marginal sediments* occur in Somerset, so ice transport most of the way seems perfectly reasonable. And physically, irrespective of the basal topography passed over by an ice sheet, ice will flow according to the slope of the top surface. At Preseli the inferred source nunatak(s) are at about 300 m OD, while between the Mendip Hills and the Cotswolds elevations widely are less than 100 m (Fig. 7). The Bristol Channel lobe of the Irish Sea Ice, at its maximum reach and within the sheet’s ablation zone (not added to by snowfall), would have thinned eastwards to some extent before completely wasting away. Crucially, during recession, the thinning ice sheet would have ceased to collect rocks from the high Preseli flanks so it no longer delivered any spotted dolerite supra-glacially eastwards from the source, and thus never added any to the erratic trail back to Pembrokeshire.

*It is a common mistake to interpret “ice-marginal sediments” as necessarily deposited at or beyond the maximum reach of an ice sheet. They will be deposited also throughout ice-sheet regression, in some instances with the outwash streams and solifluction erasing evidence of the full advance. This has happened on Gower… Erasure similarly applies where ground once covered by ice tends to be reworked under periglacial conditions of frost heave and material shattering before ultimately becoming vegetated.

Figure 8. Physical context of the contentious reach west of Stonehenge showing the range over which huge stones could be moved and the location of Boles Barrow, where the unequivocal erratic of spotted dolerite (80 cm diameter and ~340 kg) is recorded as having been found as part of a burial mound that was built some 1000 years before Stonehenge. Perhaps not so contentious after all? (Maps: https://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright).

A really simple glacial model

There is not a shred of evidence that humans transported any ‘bluestones’ all the way from Pembrokeshire to Stonehenge. The human-transport view was initiated with HH Thomas (1923) and thereafter centred on the lack of spotted dolerites in the erratic trail beyond Pembrokeshire, plus the seeming absence of evidence of ice movement onto Salisbury Plain. The supposed quarries and previous-monument sources have been disproved and the bizarre embellishment concerning the transport by cattle similarly is unwarranted. The Altar Stone transport from Scotland most sensibly did not involve humans either, while it is readily consistent with the known Irish Sea Ice Stream behaviour of Anglian times. We know that ice did transport rocks from Pembrokeshire towards Stonehenge and that it certainly penetrated at least as far east as what is now Flat Holm in the Bristol Channel (Fig. 5). Thus, in the absence of any evidence to the contrary and with ice reaching so close, surely all this begs attempting to explain the selective ice transport and the possible reach of the ice.

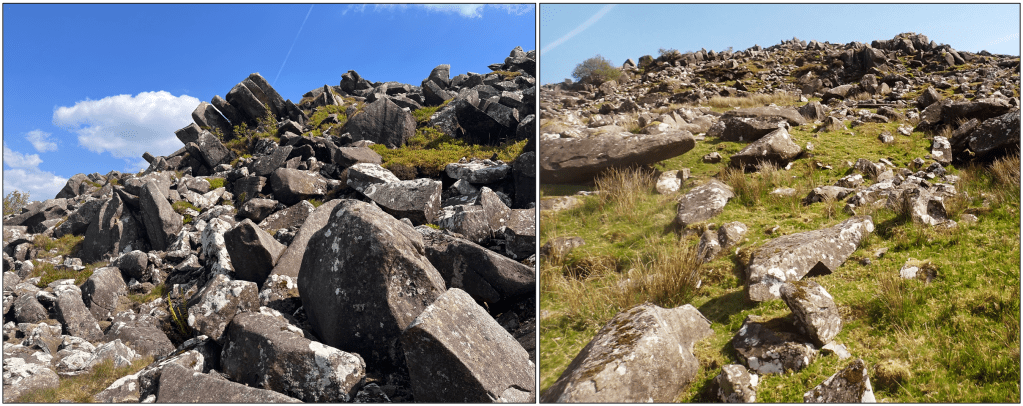

The fact that the majority of Stonehenge bluestone megaliths come only from the high flanks of Preseli speaks volumes regarding their transport. Most of the Pembrokeshire erratics on Gower and farther east clearly come from the low-ground sources Ramsey, Skomer, and St David’s. The lesser shapes and sizes of the rhyolites and dacites at Stonehenge could come from unidentified sources in the Fishguard Volcanic Group and their rounded forms speak of transport within or at the base of the moving ice. Any visit to the eastern Preseli summit area outcrops (e.g., Figs 9, 10 and 11) reveals abundant loose rocks with joint-fracture faces defining blocks, slabs and columns of the same general scale as the Stonehenge dolerite megaliths. The spotted dolerite is unique to these near-summit outcrops and open spaces between them are smoothly rounded by the erosive passage of ice (Fig. 11).

Figure 9. Outcrop of spotted dolerite at Carn Goedog (SN128 332). The slope abounds with naturally formed and fallen slabby and polyhedral (multi-faceted) columnar, weathered monoliths. Dolerite intrusions like these in the Preseli hills are common widely in western and northern Britain and everywhere their upland outcrops break, weather and collapse in similar fashion, without any human intervention.

Figure 10. Illustration of the specific collection and transport of erratics from a nunatak (inset is in Alaska, NPS). Spotted and non-spotted dolerites at Stonehenge all derive from the high craggy upper flanks in the eastern Preseli hills. The source outcrops naturally yield blocks, slabs and columns with flat-angled facets (angular polyhedral shapes), some of which arrived little-modified somewhere on or near Salisbury Plain (Fig. 4). The size-range of the dolerite blocks is characteristic of the cooling-contraction jointing that formed them; there are no bus-sized unfractured blocks and so never any huge dolerite erratics.

Figure 11. Glacially eroded and smoothed slabby outcrops occur between the craggy outcrops of the Preseli dolerites, recording the north-to-south passage of ice (right to left here).

Figure 12 (obviously not to scale). Cartoon model following the inference by Thorpe et al. (1991) that the spotted dolerite bluestones were transported on or near the ice surface (supra-glacially) from the Preseli summit source when it was a nunatak (i.e., an outcrop of rock standing proud of surrounding ice). This collection from the nunatak(s) could only occur when the ice was sufficiently thick to reach up there. Throughout the glacial activity erratics picked up from lowland sources become rounded and reduced downstream in the base of the ice (sub-glacially). During recession, however, ice-sheet thinning halted the collection of spotted dolerite from the Preseli nunatak, explaining why it is absent in the erratic populations found back towards Pembrokeshire. This model allows delivery of large bluestone erratics close enough to be collected and taken to build the various versions of arrangements near or at Stonehenge. The model also can account for the apparent insufficiency of ‘decent’ stone to finish the circle(s) and the need then to use the various lesser stones, such as the rounded erratics of rhyolite.

The problem of knowing how far the ice delivery of spotted dolerites penetrated towards Stonehenge remains ‘difficult’ and warrants further research. Perhaps so many people have taken it for granted that transport was by humans that there has been little recent focus on the glacial-periglacial geomorphology. But, if one takes away all of the disproved ‘evidences’ of human quarrying and transport, then much of the abundant so-called ‘debitage’ so widely distributed across Salisbury Plain, together with the odd contentious occurrences of small stones and boulders, all naturally becomes glacial in origin. And the Boles Boulder now safely on display in Salisbury Museum, at 340 kg and mostly well-rounded just like a large erratic, albeit with bit broken off, simply is just that… A smoking gun?

As previously admitted, this view will not settle the transport dispute, because of a “dearth of direct evidence”, but it certainly is about time that transport by ice gained its warranted recognition as by far the more likely on available evidence.

Headless chickens

From sublime to ridiculous. What follows is a brief review of some of the extraordinary headline claims made about Stonehenge, particularly involving Pembrokeshire and the bluestones.

“Recent excavations at two … bluestone sources – one for rhyolite and one for spotted dolerite – have identified evidence of megalith quarrying around 3000 BC” (Parker Pearson et al. 2017, 2020).

Fair enough, since Preseli outcrops are the long-recognised sources of Stonehenge dolerite megaliths, one would expect dedicated Stonehenge archaeologists to go and see them. However, nothing about those virtually pristine igneous rock outcrops could lead a field geologist to consider them anything other than naturally formed, including their aprons of fragmental debris. There are hundreds of such dolerite outcrops in the high grounds of British hills. They typically show jointing-related break up, involving freeze-thaw mechanical processes and weathering for tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of years, and with probable ice-related movement, plucking and scattering blocks. The extreme toughness of the rock is reflected in the fact that many of our high summits and prominent crags are of dolerite. Most of the Preseli tops are dolerite, while classic examples form the summits of Cader Idris (south Snowdonia), Moel Siabod (central Snowdonia) and Tal y Fan (north Snowdonia), and so on across northern England (e.g., the Whin Sill beneath Hadrian’s Wall), Northern Ireland (e.g., Fair Head, on the Antrim coast) and widely in western Scotland. To ‘inform’ the BBC-viewing public that quarrying by humans broke out the pillars ready for transport, especially when standing at the very summit of a perfectly natural outcrop, is ridiculous (Fig. 11). (Would remove clips from the programme and modify prose/pictures).

Figure 13. The 2021 BBC Lost Circle Revealed commentary is being delivered at the site of the yellow arrow above the outcrop at Carn Goedog. There are hundreds of perfectly natural outcrops of jointed dolerite like this dotted throughout upland Britain, some quite nearby too, and of course also abroad. Surely many thousands of years of freeze-thaw mechanical break-up cannot be overlooked? From this nonsense, ignoring simple natural processes and geology and by implication suggesting ancient quarry sites all over the country, there apparently can have been no scientific-editorial oversight and advice for the archaeologist(s). Gross mis-pleading like this, on a television channel that prides itself in distinguishing the truth, surely undermines simple enquiry and learning, undermines the credibility of actual experts, and, given the n-fold repetition of the BBC programme, is effectively misleading a host of people. Thankfully numerous sensible people have taken issue with the programme and the ‘quarries’ have been debunked and abandoned amongst aficionados, although the BBC continues the promotion. Also thankfully, most of the ground excavation has been restored to nature.

The Craig Rhosyfelin outcrop also features as a bluestone megalith quarry, in this case of rhyolite (foliated rhyolitic tuff), despite there being no known megaliths from there, just a buried stump and a few lumps and many chips recovered at Stonehenge. The provenancing is robust, for its geochemistry and rock texture, but again, despite extensive and time-consuming excavations, no quarrying could be proved. Despite objections made regarding the ‘quarries’ (e.g., John et al. 2015), there was no retraction while the focus shifted to removal and transport to Stonehenge of stones from pre-existing monuments (Parker Pearson et al. 2021). In the now infamous BBC ‘Stonehenge: The Lost Circle Revealed’ (2021) a long search eventually ‘found’ the site of a dismantled circle at Waun Mawn that was claimed to have sourced Stonehenge stones. This was proved for viewers by the imprint of a removed stone at Waun Mawn that fitted a stone at Stonehenge “like a key in a lock”, with computer-graphic confirmation. The stone that was supposed to fit is Stone 62 (see Figs 1 and 2). The interview based on this ‘clinching discovery’ invoked a revolutionary new view of collaboration between ancient societies. The trouble is, however, that robust data show that the Waun Mawn stones came from a local source (Bevins et al. 2022) unlike anything at Stonehenge, while Stone 62 came from the eastern Preseli hills not far from other known natural sources. So the whole programme, with its intense and dramatic revelations of quarrying and removal from a former stone circle, proved to be spectacularly wrong. One might say that hindsight is a wonderful thing, but contemporary expert advice was always available and ignored, and the media show on what is known to be a topic of wide interest was an information disaster.

The nonsense carried on. After the Altar Stone saga in 2024, in 2025, just this last year, there came another remarkable gem of mis-information. British Geological Survey Press (20/8/2025): “Scientists uncover secrets of Stonehenge’s mysterious cattle” and next day BBC News: “New analysis of a Neolithic cow’s tooth found at Stonehenge shows the animal likely came from Wales, reinforcing theories that cattle helped transport the enormous stones”. And “You can tell that the animal had been grazing on Palaeozoic rock, typical of those found in Wales, particularly in and around where bluestones are found… We’re beginning to see so many connections between Wales and Stonehenge. Not only is it the closest rock, but there are other links as well.” The italics are mine; nothing supports these contentions, which are false and are sheer hype.

The tooth of the cow that had been buried at Stonehenge did yield geochemical evidence of part of its life and whereabouts, primarily in analyses of element-isotopes of carbon, strontium and lead (Evans et al. 2025). We learned from carbon and strontium (C and Sr) that the 6 months or so of the cows existence that was analysed involved a migration and shift of forage while the lead (Pb) was characteristic of ancient rocks (Lower Palaeozoic) widely exposed across Wales. The rider “particularly … where bluestones are found” cannot be justified*. And the Upper Carboniferous Sandstones of the South Wales and Forest of Dean Coalfields have yielded fabulous monoliths that are impressively incorporated in major structures of the Industrial Revolution, and they are significantly closer to Stonehenge. *(A similar claim from strontium isotope analyses of cremated human remains from Stonehenge (Snoeck et al. 2018) places analyses that could originate widely across Wales as “supporting links with west Wales”…”the source of the bluestones…”, only because human involvement in stone transport from Pembrokeshire is accepted.)

The claim that the cow-tooth findings add to confirmation of the “theory” that cattle were involved in transport of the megaliths is udderly ridiculous. Apart from confusing theory and hypothesis in this media hype, the unjustified claims were disturbing as they came from the Press Office of the British Geological Survey; no sane geologist would support them. Actually, the original scientific report of the cow-tooth findings, in contrast to the hype, was quite reserved, acknowledging limitations to interpretations that should be borne in mind. What is it then, really, that causes decent science to be so compromised in the media? There certainly is cavalier ignorance on the part of media producers, whose driver seems to be promotion of viewing figures or sales…

References

Allen MJ, Chan B, Cleal R, French C & 10 others (2016) Stonehenge’s Avenue and ‘Bluestonehenge’. Antiquity 90, 352, 991-1008.

Bevins RE, Donnelly R (1992) The Storrie Erratic Collection: a reappraisal of the status of the Pencoed ‘Older Drift’ and its significance for the Pleistocene of South Wales. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 103, 129-142.

Bevins R, Ixer R (2018) Retracing the footsteps of H.H. Thomas: a review of his Stonehenge bluestone provenancing study. Antiquity 92 363, 788-802.

Bevins R, Ixer R, Pearce N, Scourse J, Daw T (2023) Lithological description and provenancing of a collection of bluestones from excavations at Stonehenge by William Hawley in 1924 with implications for the human versus ice transport debate of the monument’s bluestone megaliths. Geoarchaeology 38, 677-829.

Bevins RE, Ixer RA, Webb PC, Watson JS (2012) Provenancing the rhyolitic and dacitic components of the Stonehenge landscape bluestone lithology: new petrographical and geochemical evidence. Journal of Archaeological Science 39, 1005-1019.

Bevins RE, Pearce NJG, Hillier S, Pirrie D, Ixer RA & 4 others (2024) Was the Stonehenge Altar Stone from Orkney? Investigating the mineralogy and geochemistry of Orcadian Old Red Sandstones and Neolithic circle monuments, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 58, 104738.

Bevins RE, Pearce NJG, Ixer RA, Scourse J, Daw T, Parker Pearson M & 5 others (2025) The enigmatic ‘Newall boulder’ excavated at Stonehenge in 1924: New data and correcting the record. Journal of Archaeological Science Reports 66, 105303.

Bevins RE, Pearce NJG, Pearson MP, Ixer RA (2022) Identification of the source of dolerites used at the Waun Mawn stone circle in the Mynydd Preseli, west Wales and implications for the proposed link with Stonehenge. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 45, 103556.

Bevins RE, Pirrie D, Ixer RA, O’Brien H, Parker Pearson M, Power MR, Shail RK (2020) Constraining the provenance of the Stonehenge ‘Altar Stone’: evidence from automated mineralogy and U-Pb zircon age dating. Journal of Archaeological Science 120, 105188.

Burl A (1999) Essay extract from Glaciers and bluestones of Wales. Yale. British Archaeology 45, June.

Clarke AJI, Kirkland C (2026) Detrital zircon-apatite fingerprinting challenges glacial transport of Stonehenge’s megaliths. Nature Communications Earth & Environment doi: 10.1038/s43247-025-03105-3.

Clarke AJI, Kirkland CL, Bevins RE, Pearce NJG & 2 others (2024) A Scottish provenance for the Altar Stone of Stonehenge. Nature 632, 570-575.

Cunnington BH (1924) The “Blue Stone” from Boles Barrow. The Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Magazine CXL, Vol. XLII, 431-437.

Daw T (2025) The origins of Stonehenge’s sarsen stones: A comprehensive review of provenancing studies. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.28682.1706

Evans J, Madgwick R, Pashley V & 4 others (2025) Sequential multi-isotope sampling through a Bos taurus tooth from Stonehenge, to assess comparative sources and incorporation times of strontium and lead. Journal of Archaeological Science 180, 106269.

Field D, Anderson-Whymark H, Linford N & 15 others (2015) Analytical Surveys of Stonehenge and its Environs, 2009-2013: Part 2 – the Stones. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 81, 125-148.

Harding P, Nash DJ, Ciborowski TJR & 2 others (2024) Earliest Movement of Sarsen Into the Stonehenge Landscape: New Insights from Geochemical and Visibility Analysis of the Cuckoo Stone and Tor Stone. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 90, 229-251.

Ixer RA, Bevins RE (2010) The petrography, affinity and provenance of lithics from the Cursus Field, Stonehenge. Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Magazine 103, 1-15.

Ixer R, Bevins R (2017) The bluestones of Stonehenge. Geology Today 33, 180-184.

Ixer R, Bevins R, Pearce N, Pirrie D & 4 others (2025) Exotic granodiorite lithics from Structure 5 at West Kennet, Avebury World Heritage Site, Wiltshire, UK. Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Magazine 118, 1-18.

Ixer R, Bevins R, Pirrie D (2020) Provenancing the stones. Mapping the Stonehenge bluestones with mineralogy. Current Archaeology 366, 34-41.

Ixer RA, Turner P, Molyneux S, Bevins RE (2017) The petrography, geological age and distribution of the Lower Palaeozoic Sandstone debitage from the Stonehenge Landscape. Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Magazine 110, 1-16.

John BS (2024) A bluestone boulder at Stonehenge: implications for the glacial transport theory. E&G Quaternary Science Journal 73, 117–134.

John B (2025) Carn Goedog on Mynydd Preseli was not the site of a Bluestone Megalith Quarry. Archaeology in Wales 63, 5-18.

John B, Elis-Gruffydd D, Downes J (2015) Observations on the supposed “Neolithic bluestone quarry” at Craig Rhosyfelin, Pembrokeshire. Archaeology in Wales 54, 139-148.

Leivers M (2021) The Army Basing Programme, Stonehenge and the emergence of the Sacred Landscape of Wessex. Internet Archaeology 56. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.56.2

Neilson JC (2008) From slab breakoff to triggered eruptions: Tectonic controls of Caledonian post-orogenic magmatism. PhD thesis, University of Liverpool, 518 pp.

Neilson JC, Kokelaar BP, Crowley QG (2009) Timing, relations and cause of plutonic and volcanic activity of the Siluro-Devonian post-collision magmatic episode in the Grampian Terrane, Scotland. Journal of the Geological Society, London 166, 545-561.

Oliver GJH, Wilde S, Wan Y (2008) Geochronology and geodynamics of Scottish granitoids from the late Neoproterozoic break-up of Rhodinia to Palaeozoic collision. Journal of the Geological Society, London 165, 661-674.

Parker Pearson M (2023) Stonehenge. Journal of Urban Archaeology 7, 147-168.

Parker Pearson M, Bevins R, Ixer R & 3 others (2020) Long-distance landscapes: from quarries to monument at Stonehenge. Megaliths and geology. Boaventura, Mataloto & Pereira (eds), pp 151-169.

Parker Pearson M, Pollard J, Richards C, Welham K (2017) The origins of Stonehenge: on the track of the bluestones. Archaeology International 20, 52-57.

Parker Pearson M, Pollard J, Richards C, Welham K & 6 others (2021) The original Stonehenge? A dismantled stone circle in the Preseli Hills of West Wales. Antiquity 95, 85-103.

Scourse JD (1997) Transport of the Stonehenge Bluestones: Testing the Glacial Hypothesis. Proceedings of the British Academy 92, 271-314.

Snoeck C, Pouncett J, Claeys P, Golderis S & 6 others (2018) Strontium isotope analysis on cremated human remains from Stonehenge supports links with west Wales. Nature Scientific Reports (2018) 8:10790.

Strahan A, Cantrill TC (1904) Geology of the South Wales Coalfield. Part VI. The country around Bridgend. Mem. Geol. Surv. Great Britain.

Strahan A, Cantrill TC, Dixon EEL, Thomas HH, Jones OT (1914) The geology of the South Wales Coalfield, Part XI. The country around Haverfordwest. London: HMSO.

Thomas HH (1923) The source of the stones of Stonehenge. Antiquaries Journal 3, 239-260.

Thorpe RS, Williams-Thorpe O, Jenkins DG, Watson JS (1991) The geological sources and transport of the bluestones of Stonehenge, Wiltshire, UK. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 57, 103-157.