Two contrasting places on peninsular Gower are renowned for flooding – Green Cwm, from Llethrid down to Parkmill, and ‘Llanddewi corner’ on a reach of the Burry Pill. They could hardly be more different. The occasional flooding of Green Cwm ‘dry valley’, which in recent years seems to have become more frequent, results from almost complete saturation of the limestone aquifer and filling of cave passages so that the ground-water level (water table) is at or close to the valley floor and excess rainwater has to flow over the surface. Water level and hence flooding inside Llethrid cave is now monitored continuously (thanks to support from the Gower Society) and is linked to stream level and rainfall recorded nearby. The water behaviour of Green Cwm is extensively described in the Gower Landscape book, although much remains to be understood. Only a brief account is provided here, before discussing Llanddewi.

Flooding of Green Cwm essentially results from the underground system there being unable to take exceptional volumes of rainwater running off its catchment following intense downpours. The Green Cwm cave system before and during the Last Glacial Maximum advance, some 23,000 years ago (see below), probably could have taken a lot more water, but during the ice retreat (recession) a catastrophic flow of glacial debris entered the valley and penetrated far into the caves, substantially blocking them and their original sink holes. For those who know Gower, the pre-glacial Green Cwm would have been similar to the upper reach of Bishopston Valley today, with naked limestone exposing open caverns and pits that take most flood water. The contrasting flat floor of Green Cwm below Llethrid and the large amounts of muddy-pebbly debris underground for at least 1 km downstream together record the late-glacial inundation that constricted the previously open caves. The catastrophic flow of glacial debris most probably resulted from breaching of a lake formed in front of the melting ice as it retreated northwards off what are now the Pengwern, Forest and Welsh Moor commons.

The flooding at ‘Llanddewi corner’ (Fig. 1) similarly has a rather cryptic Ice Age explanation. The right-angled corner in the main road between Knelston and Scurlage used to terrify me as a school-boy-pillion passenger on my friend’s 650 cc motorbike, as he’d drop the bike so far that my footrest scraped along the road surface all the way round… I hoped for flooding that might slow us down! Like Green Cwm, the Llanddewi flood typically follows a period of intense rainfall and is much more than one of the many ephemeral puddles formed immediately by local runoff in heavy rain. It forms along the Burry Pill, can back up 1 km to Scurlage, and is a narrow lake formed across the road and adjacent stream banks for almost 2 km towards Burry, flowing with increasing speed along there.

Figure 1. Llanddewi corner viewed upstream along the road to Scurlage, with the Reynoldston fire engine in characteristically brown, mud-laden water from the saturated fields farther south and west. Photo is a Facebook video grab, courtesy of Neil Barry.

The courses of the Burry Pill drainage seem remarkable in originating over a wide arc close to the southwest coast of Gower, locally only about 1 km inland, and then crossing the peninsula to enter the Loughor (Burry) Estuary close to Llanmadoc on the north coast. Also striking was the sheer beauty of the flora along the course of the stream, especially from Llanddewi to Burry and on to Stembridge. Extensive beds of yellow iris (yellow flag) and meadowsweet were characteristic, regrettably but sensibly now widely cleared out, this being significant…

Flooding and hence blockage of the road by Llanddewi is important for inhabitants of southwestern Gower, because, unless bold enough to tackle the narrow and steep lanes via Hangman’s Cross and Penrice or the back of Oxwich, the main road there is the only way out to Swansea or to the ‘dark side’. It is locally held by some, ‘from decades of experience’, that the flooding by Llanddewi can be related to the sea tides. Notionally in this view, high spring tides correlate with flooding that results from heavy rainfall, with the high tidal water causing backing up of water in the draining culverts and ditches. This is an interesting idea, indeed, but Llanddewi corner is at 40 m OD (131’ above sea level) and extensive reaches of the Burry Pill downstream from there are freely open draining (Fig. 2) and never encroached by the sea. Although the area is underlain by permeable limestones, seawater does not penetrate beneath the peninsula (evidence from Parkmill and Llanrhidian springs) and even if it did tidal depth changes could not affect water more than a few metres above the sea surface level. The likely explanation of the flooding is, perhaps, a little interesting…

Figure 2. Burry Pill downstream from Burry is free-draining with narrow flood-plain banks that are inundated during rainwater floods. Heights above sea level (Ordnance Datum) are given. A. Upstream from Fairy Hill; B. By Western Mill; C. Below Packhorse Bridge; D. Below Cheriton Bridge.

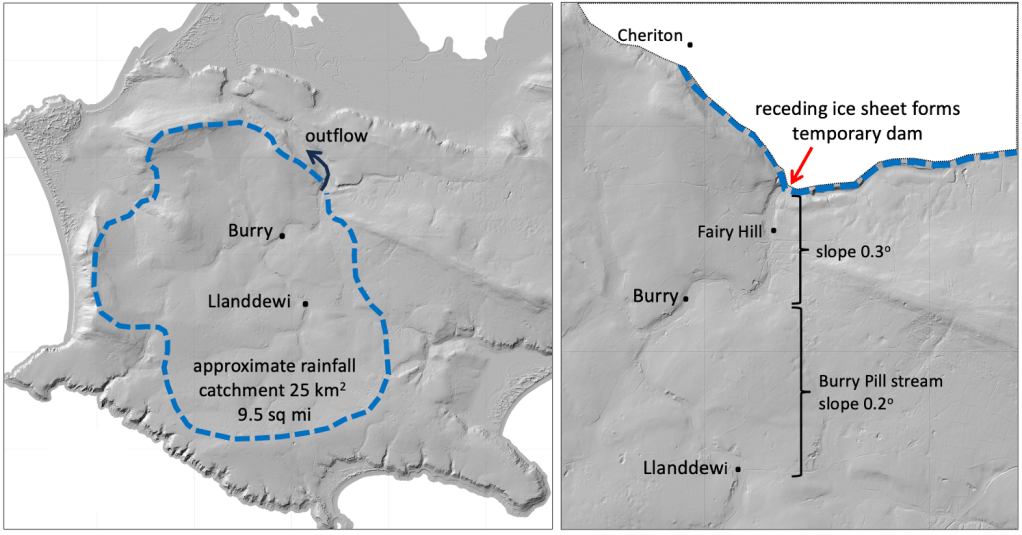

A key feature of the Burry Pill is that it has a large rainfall catchment predominantly floored by low permeability pebble and clay-rich glacial sediment (till). Essentially it is a low-profile, shallow basin roughly 25 km2 in area (about 9.5 square miles; x7 larger than the Llethrid catchment). Runoff from the fields and ditches during torrential rain is spectacular, and nearly all of this water becomes focussed to flow by Llanddewi corner. While there will be some leakage of water through the till, and direct entry into the underlying limestone where till is absent, groundwater in the limestone ultimately re-joins surface water via several significant springs along the Burry Pill. At Bury Head a substantial persistent spring enters from the northwest, and it is safe to assume that the stream in this vicinity carries most of the catchment rainwater.

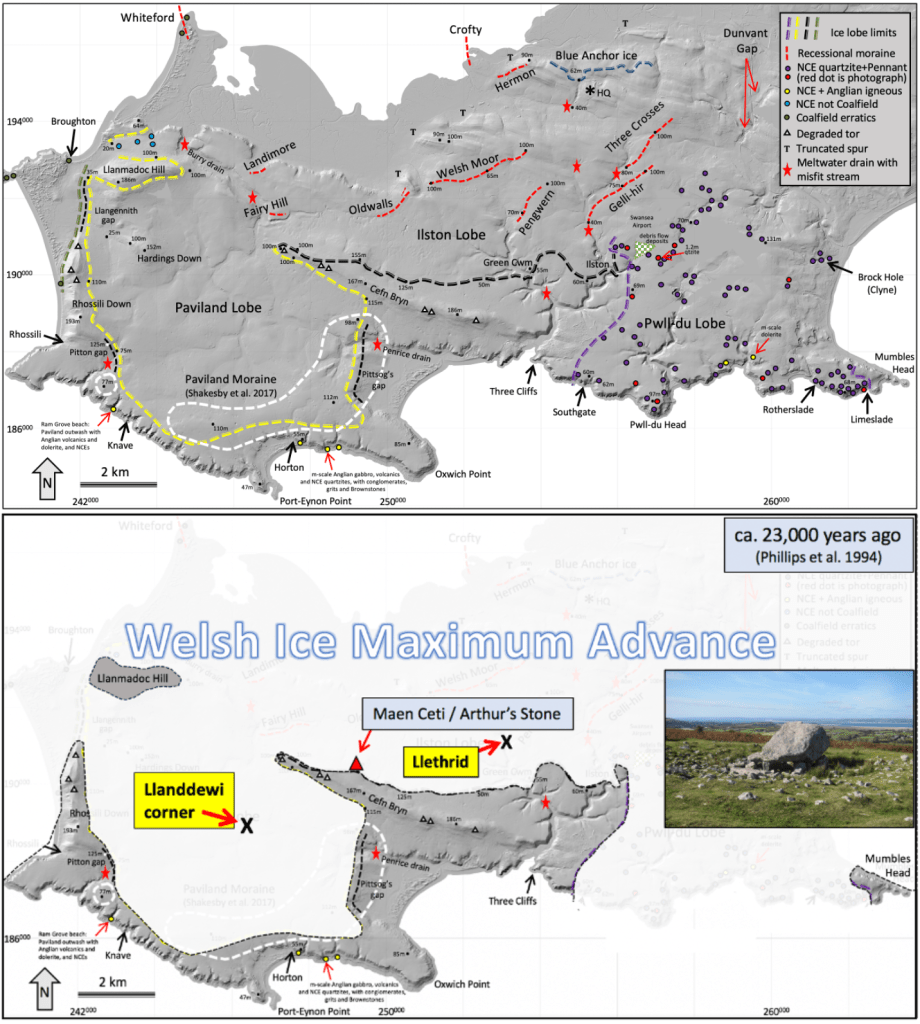

Perhaps a little interesting. The shallow-basin of the Burry Pill catchment was substantially moulded by advance and retreat of a lobe of glacier ice during the last glaciation, some 23,000 years ago. The maximum extent of the Welsh Ice on Gower was mapped for the Gower Landscape book (Chapter 3). The raw data are shown in Figure 3, with the extent of the so-called Paviland ice lobe shown diagrammatically beneath.

Figure 3. Top shows the mapped distribution of main glacial features on the Gower peninsula and bottom shows the inferred maximum ice cover based on the mapped features. The yellow ice-lobe limits distinguish the Paviland Lobe, which built the basin-bounding mounds of till (moraine) and deposited the low permeability basin floor. Llanddewi corner is fairly centrally located. The iconic Arthur’s Stone (inset) was delivered from north of the South Wales Coalfield by the Welsh Ice. Base image contains Natural Resources Wales information; NRW and Database Right. LiDAR from http://lle.gov.wales/home.

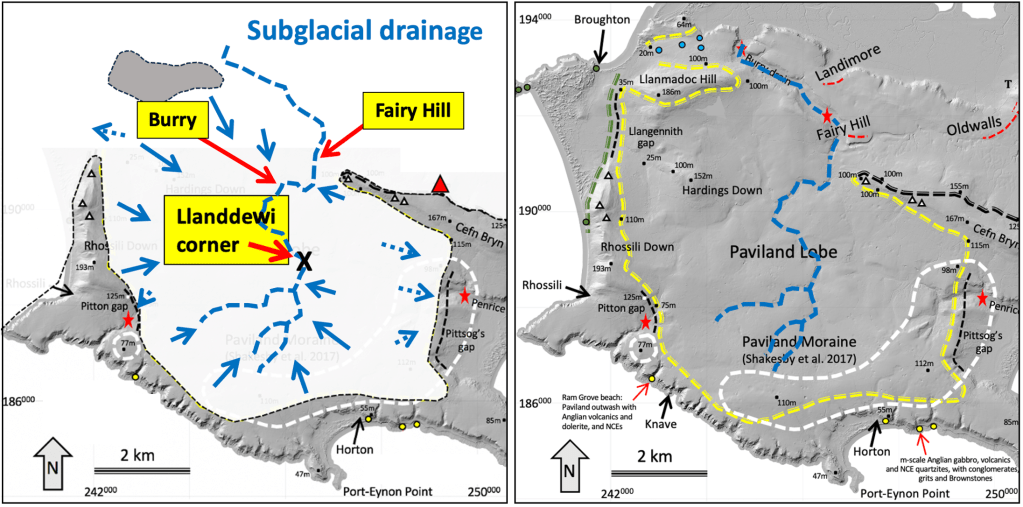

Figure 4. Left. Llanddewi corner and Burry located on what most probably was the last trace of the main subglacial drainage, which is inherited for now. Whereas many glacier streams drain downhill away from the ice, in the direction of ice flow, the main Paviland subglacial drainage was primarily northwards back beneath the ice. This reflects the fact that the bedrock slope was towards the north, down into the valley that at the time was full of Welsh Ice and is now occupied by the Loughor Estuary. The dashed blue arrows are where drainage may have been outwards away from the ice lobe when it was at maximum extent. Right. Paviland ice lobe outlined with the present-day main elements of the Burry Pill drainage highlighted as dashed blue lines. Remnants of the Welsh Moor – Oldwalls – Fairy Hill Moraine (Fig. 3 top) are highlighted (dashed red) because the feature probably represents a stage in glacier recession when the catchment drainage basin was for a while blocked by ice on the north side.

The 2024 topographic map (https://datamap.gov.wales/maps/new#/) shows that the stream slope along the course of the Burry Pill from Llanddewi corner to Burry is only 0.2o (one fifth of one degree of downstream slope), while farther downstream it steepens to 0.3o and then 0.45o where the flood flow accelerates and the stream is free draining (Figs 2 & 5).

Figure 5. Flooding is due to a large catchment having a low slope to a constricted outflow. It is a peculiar and unfortunately lasting legacy of the last Ice Age.

The main cause of the Llanddewi flooding is the extremely low slope along the 2 km to Burry, which in turn reflects the low slope of the original subglacial drainage. As the Paviland ice lobe melted back northwards, it, with the water beneath it, would have formed a blockage that maintained a low stream profile, possibly even a lake at times, so there was no strong tendency then to erode the stream bed.

We can be certain that the receding ice temporarily halted its melting back when it built the moraine that is well defined across Welsh Moor and limps westwards via Oldwalls to the vicinity of Fairy Hill (see Fig. 3 top & Fig. 5 right). Somewhat speculatively, this temporary barrier downstream from Burry could have prevented stream-bed steepening (technically nick-point migration) from working back into the upstream basin.

Evidently the outflow of the extensive rainfall catchment has to traverse a very low slope just where potential throughput is maximum. It then is obvious that in order to minimise Llanddewi corner flooding it was essential to keep drainage conduits and channels through that section to Burry clear of flow-impeding obstructions – hence the built conduits and channel excavations, and the loss of the yellow iris and meadowsweet beds. (Peter Kokelaar January 7th, 2024).